Why State and Federal Voting Rights Legislation go Hand-in-Hand

By Marisa Wright

On August 23, 2023

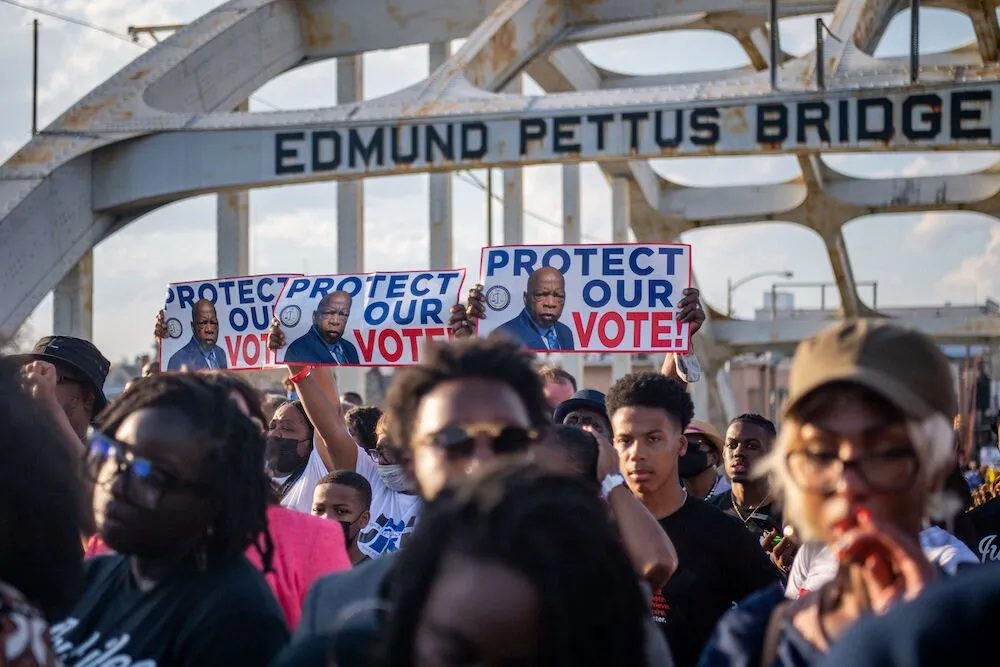

Over the past decade, the federal Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 has suffered two significant blows at the hands of the U.S. Supreme Court — and Congress has repeatedly failed to act. Now, state lawmakers are stepping into the void to ensure the right to vote remains meaningful in the United States by enacting state versions of the federal law, known as state voting rights acts. Six states have already passed their own VRAs, while several others have similar efforts underway.

This work comes at an especially critical time in the wake of recent Supreme Court decisions in Allen v. Milligan and Moore v. Harper, which solidified that state VRAs constitute a viable and important way to protect and advance voting rights in the United States. Milligan made clear that voter protections, such as those in Section 2 of the federal Voting Rights Act, are constitutional — and that states may depart from the federal framework when crafting their own voting rights acts. And Moore underscored the critical role for state courts in protecting the right to vote. At this important moment, a tandem approach of restoring and expanding federal voting rights legislation along with passing individual state VRAs is essential for providing the most robust voting protections for all voters in the United States.

HOW VOTING RIGHTS HAVE BEEN WHITTLED AWAY BY THE SUPREME COURT

The Voting Rights Act’s passage in 1965 marked a critical time in American history, finally concertedly protecting access to the ballot box for members of historically marginalized groups. The VRA broadly prohibits discrimination in voting based on race, color, or language minority status. In doing so, it enfranchised millions of Americans who had previously been shut out of political participation. But, in the decades since, some of these protections have receded.

One of the VRA’s key provisions is called preclearance, a requirement that jurisdictions with documented histories of discrimination first seek approval for any changes to election rules or administration from either the U.S. Department of Justice or a federal court. By requiring pre-approval, the VRA sought to prevent discriminatory practices from going into effect in the first place.

In 2013, however, the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder struck down the framework that determined which jurisdictions were subject to the preclearance requirement, effectively gutting this key enforcement measure. In the case, officials from Alabama, a state notorious for its racially discriminatory voting laws, dubiously claimed that preclearance wasn’t necessary anymore because racial discrimination in voting was no longer a pressing problem in the places subject to the protection. In an opinion written by Chief Justice John Roberts, the Supreme Court struck down the framework Congress designed to determine which places are covered, leaving preclearance functionally defunct, except when ordered by a court to address intentional discrimination.

In the aftermath of Shelby County v. Holder, many states created obstacles to voting. As a report from LDF’s Thurgood Marshall Institute, “Democracy Diminished,” described, “Common [post-Shelby] changes at the state or local level that potentially are discriminatory include: reducing the number of polling places; changing or eliminating early voting days and/or hours; replacing district voting with at-large elections; implementing onerous registration qualifications like proof of citizenship; and removing qualified voters from registration lists.” These voting obstacles typically have a disproportionate impact on people of color, language minorities, low-income voters, and naturalized citizens.

And yet, the Supreme Court didn’t stop there. In 2021, the Court made it more difficult for voters to vindicate their rights under Section 2 of the VRA in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee. Notably, Section 2 provides critical protection against denying the rights of voters in a minority group, barring states from using any “standard, practice, or procedure” that “results in a denial or abridgement” of the right to vote on account of race.

BARRIERS PERSIST: WHY VOTING PROTECTIONS ARE STILL NEEDED

To understand why state VRAs are so crucial today, it’s first important to consider why voting rights protections were, and continue to be, necessary in the first place. Although they create protections for all voters, state-level voting laws are an especially important tool for racial justice. By building on the federal VRA with legal tools designed to counter modern forms of discrimination in voting, state VRAs can help fulfill the federal law’s original promise of ensuring equal access to the ballot box regardless of race, color, or language.

During the Jim Crow era, Black people, particularly in the South, effectively did not have the right to vote, despite the protections of the 15th Amendment. White supremacist state lawmakers erected significant obstacles to voting, including poll taxes, grandfather clauses, literacy tests, and other bureaucratic restrictions to deny Black people the ability to vote. Even worse, some members of the public, law enforcement, and even elected officials attempted to suppress Black voters through harassment, intimidation, economic retaliation, and physical violence when they tried to register or vote. The result was unsurprising — few Black people were registered to vote, and they had little to no political power.

Although they may look different from the Jim Crow era, today’s vote suppression tactics continue to target and disproportionately harm voters of color. Even today, people of color are more likely than white people to face hurdles to accessing the ballot box, such as longer wait times and polling place consolidations, and are also disproportionately affected by aforementioned obstacles to voting, like strict voter ID laws and limitations on voting by mail. These barriers contribute to a racial disparity in voter turnout, which skyrocketed following the 2013 Shelby County decision.

In fact, “Turnout disparities between white and Black voters increased substantially in Shelby’s aftermath in five out of the six states fully covered under the VRA’s preclearance protections,” LDF Deputy Director of Litigation Deuel Ross indicated in his written testimony submitted to the United States House Committee on House Administration’s Subcommittee on Elections for a May 2023 hearing. As Ross pointed out, in Alabama pre-Shelby (in 2012), Black and white voter turnout was nearly the same, but in, 2020, Black turnout fell almost eight percentage points behind white turnout. And, in 2022, substantial disparities between Black and white turnout compared with previous recent elections persisted and increased, including in Georgia, South Carolina, Louisiana, and North Carolina, Ross noted.

The weakening of the federal Voting Rights Act means that state VRAs will need to fill a bigger hole than ever before, both as we wait for the restoration of comprehensive federal voting rights legislation — but also even when this legislation is passed. Although state VRAs take inspiration from the federal law, they are guided by the maxim that the states are the laboratories of democracy. Each one looks a little different from the others — an effort to build on the federal VRA by adapting different legal tools to each state’s unique circumstances to protect voting rights most effectively.

STEPPING IN: HOW STATE VRAS CAN HELP FILL THE GAP IN VOTING RIGHTS

In 2002, California set the standard when it passed the first state VRA in the country, seeking to address “the continuing harm of vote dilution caused by racial polarization in at-large voting systems throughout California,” per a Lawyers’ Committee fact sheet about the legislation. One of the California VRA’s provisions provides voters of color with a streamlined way to challenge at-large elections. At-large elections are those in which every voter casts ballots for all candidates in a jurisdiction. At-large elections can sometimes be discriminatory because they can prevent voters of color in a jurisdiction from electing their candidates of choice, since a white majority in that same jurisdiction can elect their preferred candidates, drowning out the preferences of voters of color.

Over the last several years, a handful of other states have passed their own VRAs: Washington in 2018, Oregon in 2019, Virginia in 2021, New York in 2022, and Connecticut in 2023. Notably, LDF played a critical role in supporting the enactment of New York and Connecticut’s VRAs. Several other states have also recently expressed interest in or taken steps to enact their own VRAs. In recent legislative sessions, legislators have introduced VRAs in Maryland, Michigan, Illinois, and New Jersey, while Washington in April enacted improvements that enhance its current voting rights law.

Some of the recently-passed and proposed state VRAs contain voter protection provisions that go beyond federal law. New York and Connecticut’s VRAs, the NYVRA and CTVRA, respectively, contain a “democracy canon” that directs courts to construe election and voting laws liberally in favor of protecting the rights of voters and ensuring minority groups “have equitable access to fully participate in the electoral process.”

Upon its passage, LDF called the NYVRA a “landmark victory for Black voters,” noting that as “Black and Brown voters face the greatest assault on their voting rights since the Jim Crow era, we are relying on states to protect the right to vote and safeguard our democracy.” Moreover, in a June 2023 press release celebrating the CTVRA’s passage, LDF President and Director-Counsel Janai Nelson emphasized that the law’s “comprehensive provisions make the CTVRA the strongest state voting rights act yet, setting a new standard for other states — and Congress — to follow.”

The New York, Virginia, and Connecticut VRAs (along with the proposed Maryland, Michigan, and New Jersey laws) include a provision mandating jurisdictions provide language-related assistance in voting and elections to language-minority groups. Doing so lowers barriers for voters whose first language is not English, allowing them equal access to election-related information.

Strong protections against voter intimidation efforts are also a new feature of the bills currently winding their way through state legislatures in Maryland and New Jersey — and they are already found in the CTVRA and the NYVRA. After the violence on display during the 2020 election and the Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, these safeguards are meant to address “recent efforts to stoke fear, spread disinformation, and obstruct access to [the] ballot box in naturalized citizen communities and communities of color,” according to the ACLU of Maryland.

Overall, “state VRAs are an excellent tool for protecting millions of Black voters while also building momentum for Congress to fully restore and strengthen the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965,” LDF Senior Policy Counsel Adam Lioz tells LDF in an interview for this piece. “That’s why we have made them our top affirmative voting rights priority at the state level.”

Lioz also adds that “A core piece of LDF’s state VRA model is bringing preclearance to the state level. Preclearance is critical because it can stop discrimination before it occurs. It’s based on the simple idea that when it comes to a matter as fundamental as the right to vote, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

“State VRAs are an excellent tool for protecting millions of Black voters while also building momentum for Congress to fully restore and strengthen the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965. A core piece of LDF’s state VRA model is bringing preclearance to the state level. Preclearance is critical because it can stop discrimination before it occurs. It’s based on the simple idea that when it comes to a matter as fundamental as the right to vote, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

– ADAM LIOZ

LDF SENIOR POLICY COUNSEL

STRONG FEDERAL VOTING PROTECTIONS ARE STILL NEEDED

While state VRAs are critically important, they are not a substitute for federal voting protections, as a state-by-state approach still leaves millions of Americans in states without such laws unprotected from violations of the most fundamental right we have as citizens. Therefore, the U.S. House and Senate must also act. Congress should restore the Voting Rights Act to its full force by passing the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act, and it should also pass the Freedom to Vote Act, which sets minimum standards for voting access across the country.

If these two bills are passed, state VRAs will nonetheless remain essential tools for protecting and advancing voting rights. According to the Harvard Law School’s Election Law Clinic’s website, protections implemented through state voting rights laws “can reduce disparities in racial turnout, increase diversity in local elected offices, and improve local governments’ responsiveness to their constituents.” And, as Lata Nott of the Campaign Legal Center emphasizes, while “the federal VRA is still the best tool for most voters to fight voting discrimination … states can go beyond that to create an even better tool for their own citizens.”

States have an obligation to ensure all voters have an equal opportunity to elect representatives who are responsive to their needs and concerns. By implementing their own voting rights acts, states can lead the way toward protecting voting rights for all Americans.

This piece was republished from the Legal Defense Fund.