Environmental racism is rampant in Florida, but don’t mention it

From incinerator smoke to toxic waste sites, Black residents face a lot of health hazards

By Craig Pittman

On July 20, 2023

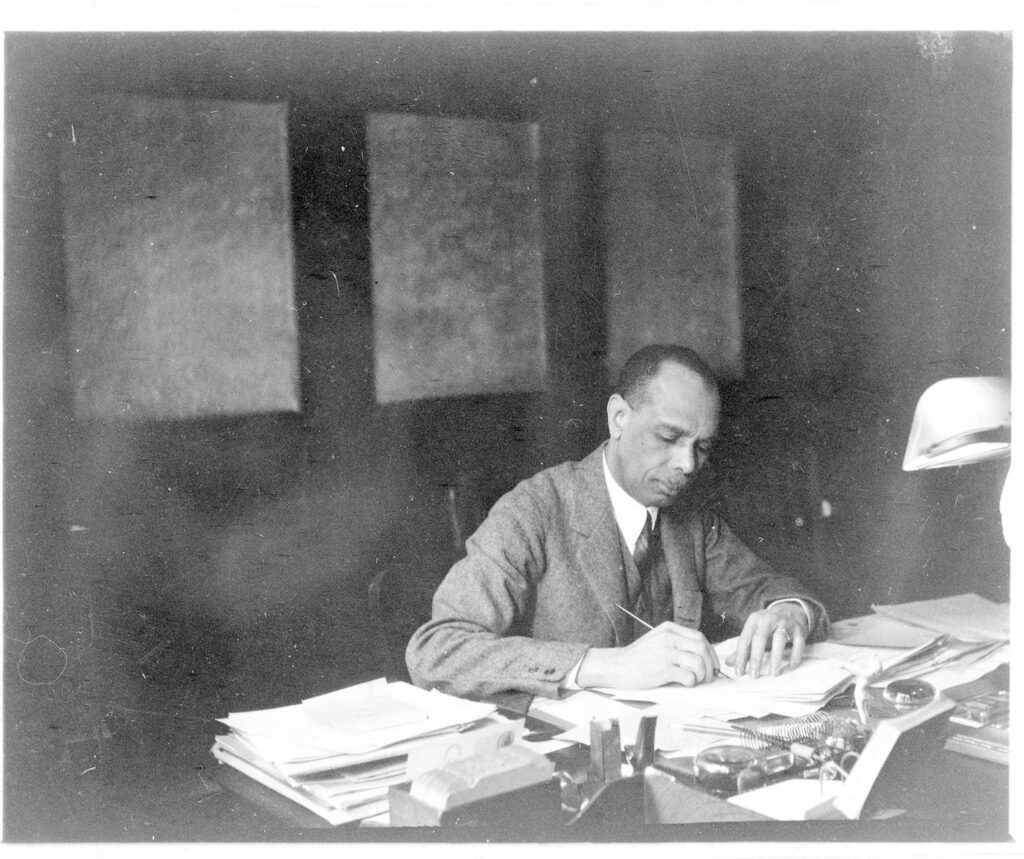

Last year I wrote a magazine story about James Weldon Johnson, one of the most remarkable Florida men ever. He was a Black lawyer, educator, poet, novelist, diplomat, and civil rights activist from Jacksonville. Among other accomplishments, he and his brother wrote what’s been dubbed “the Black National Anthem.”

The Johnsons composed “Lift Every Voice and Sing” for a choir of 500 children from a segregated school to sing for a 1900 celebration of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday.

A year later, after a confrontation with a white lynch mob, the brothers left Jacksonville. The Johnsons didn’t realize until years later that those children had spread awareness of their anthem all over the nation and it had caught on in a big way.

Because of my story, I was invited to talk about Johnson as part of a two-day conference put on every June for public school teachers.

I know the idea of me teaching teachers would probably horrify some of my own teachers. Instead of “magna cum laude,” I graduated “Lordy, how come?” Perhaps that’s why I was eager to do it.

The conference is sponsored by the state’s African American History Task Force, created in 1994 when the Legislature first began requiring the teaching of Black history without setting aside any money for it (which is a very Florida thing to do).

More than 300 people registered to attend, according to the Tampa Bay Times. And then they had to wait, as a newly constituted task force voted at the last minute to postpone the conference.

The conference organizers were awaiting direction from the state Department of Education on complying with some laws recently passed by the Legislature about never making white people uncomfortable while discussing history.

The new plan calls for the conference to occur in August and take just a day. Last week I was informed that my services talking about my Johnson story are no longer required.

As Kurt Vonnegut used to say, “And so it goes.”

But just in case the task force calls on me again, I want to be ready with a more appropriate topic. The task force seems to be allergic to any discussion of lynch mobs and such from the past. Instead, I have been gathering intel about more recent events.

Pretend what follows is a series of Power Point slides on what I found out.

From Pensacola to Pahokee and beyond, examples abound of what’s called “environmental racism.” This is when some health hazard has been planted smack in the middle of a community of people who are Black or Hispanic.

Purely by coincidence, of course! I’m sure nobody meant to do that!

A Florida law (more about that in a bit) calls for “the fair treatment of all people of all races, cultures, and incomes with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.”

But that principle is followed in Florida about as closely as the speed limits on I-75. Environmental racism is rampant.

“There’s tons in Florida,” said Abigail Fleming, associate dean of the University of Miami law school’s environmental justice clinic. “Any environmental hazard, like a toxic waste dump or a municipal trash incinerator, is an example.”

Then she told me about Old Smokey. Next slide, please!

Nothing to see here!

“Old Smokey” was a trash incinerator that Miami opened in what the Miami New Times described as “a segregated, black-only part of Coconut Grove” in 1925.

“Sometimes you had trouble breathing; the kids were coughing. It was so bad you’d have to come inside and close the windows,” one longtime resident told the paper. “Soon as you hung the clothes on the line to dry, they’d be covered in soot.”

The incinerator was shut down in 1970 by a court order that declared it a public nuisance. This happened, the paper reported, “only after schools were desegregated and white kids were forced to go to school nearby.” But I bet that was just a coincidence, too!

Miami officials knew for years that the ash from Old Smokey had contaminated surrounding areas with arsenic, barium, and lead, among other things. But the residents didn’t find out until 2013. Purely a bureaucratic oversight!

This is the point at which someone from the state Education Department would harrumph like Gov. William Le Petomane’s staff in “Blazing Saddles” and complain that I am trafficking in ancient affronts, which is a no-no. After all, that discovery of health hazards happened 10 whole years ago.

But folks are still grappling with the ramifications. In fact, Miami officials keep trying to wiggle out of a lawsuit that Old Smokey’s victims filed in 2017. Twice last year a judge denied the city’s motion to toss it out.

As it happens, Old Smokey wasn’t the only waste incinerator in Miami-Dade County. There was one in Doral, too, run by a company called Covanta. New slide!

In February, the Doral incinerator burned out of control for three weeks. Yes, it’s ironic that an incinerator caught fire. But the people living near it weren’t laughing about all the thick smoke. Once the blaze was extinguished, the incinerator was shut down.

Miami officials echoed Leslie Nielsen in “The Naked Gun,” saying that there was nothing to see and everything was fine. But a report last month from the environmental law nonprofit Earthjustice and grassroots group Florida Rising detailed toxic quantities of air pollution from the fire.

According to those groups, “93% of people living within 3 miles of the Doral incinerator are people of color and 36% live below the poverty line.” Well gee, they should have bought in a more upscale neighborhood far from an incinerator!

How much danger they’re in

A few years ago, I interviewed a dentist named Robert Hayling, who led protests in St. Augustine that eventually spurred Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

During the protests, angry Klansmen broke Dr. Hayling’s hands so he couldn’t work. The sheriff showed up before they could do worse — then arrested him for assault.

“Some said I didn’t have enough sense to know how much danger I was in,” he told me.

My next slide: Last year, Earthjustice filed a complaint with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency accusing Florida’s own Department of Environmental Protection of violating that same Civil Rights Act.

The organization complained that DEP had discriminated against minorities in the siting of Florida’s 10 incinerators. Although 10 may not sound like much, Florida has more “trash-to-cash” facilities for burning garbage and producing electricity than any other state. Our fine Legislature wants even more of them.

The Earthjustice complaint said that burning garbage “emit[s] pollutants known to cause cancer, respiratory and reproductive health risks, increased risk of death, and other health impacts.”

Rather than putting these sources of disease into white neighborhoods, the complaint said, they’re in minority communities. That must be driven by the low price of land, not some sort of bigoted disdain for the people living there, right?

Last month, the EPA wrote to DEP Secretary Shawn Hamilton — the DEP’s first Black secretary, by the way — to say that it was going to look into the Earthjustice complaint about three of the incinerators.

One was the site in Doral. The other two are in Tampa: the McKay Bay Waste-to-Energy Facility, in which Tampa’s municipal government burns 360,000 tons of waste a year; and the Hillsborough County Resource Recovery Facility, which torches more than 544,000 tons of waste a year.

This investigation maaaaaaaay be embarrassing for Hamilton. His bio says that before becoming secretary, he “served as the agency’s environmental justice coordinator, with responsibility for providing statewide guidance on sensitive environmental justice issues.”

But hey, nobody’s perfect. Just ask the EPA. Next slide, folks!

On top of Mount Dioxin

This one happened in my hometown of Pensacola, where the Escambia Wood Treating Co. operated from 1942 to 1982. The company produced power poles and other wood products coated with creosote and PCBs to make them last.

The managers were white, the workers Black. A lot of the workers lived in homes around the site where all those toxic chemicals were winding up in the soil and water.

When the EPA discovered the toxic waste, the agency didn’t bother to meet with the Black neighbors. Instead, it sent cleanup crews in moon suits to excavate the waste — even as kids played just outside the fence.

Before long, the EPA had piled up 250,000 cubic yards of toxic soil that soared 60-feet-high, creating what locals dubbed “Mount Dioxin.”

Soon people living nearby recorded increases in nosebleeds, nausea, and skin rashes due to the dust blowing off the mound.

“This recklessness would not have occurred in non-minority or wealthy neighborhoods,” one local activist commented.

People in the community began pushing the EPA to buy houses around the site and move everyone to safety. Persuading the agency to do that took five long years.

In 1997, the EPA finally agreed to relocate nearly 400 households from around the site. Most had moved by 2001. That’s how Mount Dioxin became what the Pensacola News Journal called “the third-largest permanent Superfund relocation in U.S. history.

“Oh,” the task force might say, “this is more ancient history, but at least it involves the Clinton administration and not a Republican.”

Well, yes, but thanks to both Democrats and Republicans in Congress, the cleanup has dragged on for more than 20 years. That’s partly because they ran out of money.

Fortunately, the $1.2 trillion Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal that passed two years ago put $1 billion into Superfund projects. The EPA announced it would use some of that money to complete the cleanup at Escambia Wood. Of course, now some in Congress want to scale back that infrastructure spending, but I’m sure race has nothing to do with that.

Anyway, having discussed Pensacola, let’s move on to Pahokee. Next slide!

Smoke got in his eyes

Did you see those stories last month about how thick smoke from Canadian wildfires was wafting down to American cities, making the air unbreathable? This week the smoke came back, so that 18 states are under air quality alerts from Montana to New York and as far south as Georgia.

Imagine what it would be like to live with that unbreathable air for months.

That’s what happens in the South Florida towns of Pahokee, South Bay, Clewiston, and Belle Glade. From October to May every year, Florida’s sugar companies burn their 400,000 acres of fields to prepare for harvest, thus getting rid of the outer leaves of the cane stalks.

The smoke showers down what residents refer to as “black snow” that coats their houses, cars, and lungs.

“These are mainly communities of Black and Brown residents,” said Pahokee native and former mayor Colin Walkes when I talked to him about this in 2021. “People have been living with these conditions for many years.”

But if the wind shifts so the smoke blows towards eastern Palm Beach County, where the white people (including a certain golf club owner and his collection of classified documents) live? Then state rules say they have to shut down the burn.

And when a class action took aim at this practice two years ago, the Legislature passed a bill that said no one could sue over it. Our avowed anti-sugar governor signed it. But maybe he didn’t mean to! Maybe the smoke got in his eyes!

I contacted Walkes this week to ask how things were going. He said he thinks all the bad publicity has prompted the sugar barons to cut back about 10 percent. But that’s far from enough.

“We’re still dealing with the same smoke and ash,” he said. “It’s a serious thing, but people don’t take it seriously.”

Last week, The Palm Beach Post ran a story pointing out that the county’s health department never posted any warnings about the smoke from the sugar field. That’s even though a Florida State study last year found that it shortens people’s lives.

A former director said the health department lacks jurisdiction over such a health hazard.

“What we know is that if there’s sugar burning, that people who have asthma are more likely to be going to the ER or their doctor,” she told the paper. “So, what we try to do is teach them what to do, to stay indoors.”

Got that? Stay indoors for eight months and you’ll be fiiiiine!

Now about that law I mentioned …

Mostly blank

Last slide! The only Florida law that mentions the concept of “fair treatment” of people of all races when it comes to the “development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies” is the one involving brownfields.

Those are properties where development is hampered by hazardous waste. But that’s the only time state law says anything like that. There’s no mention of it in the description of the DEP’s mission or anywhere else.

At Fleming’s suggestion, I looked on a website called “Environmental Justice State By State,” which was mostly blank for Florida. I found this fascinating tidbit:

In 1994, Florida established an Environmental Equity and Justice Commission and told its 17 members to find out if low-income and minority communities are more at risk from environmental hazards than the general population. Two years later, in its report, the commission said yes.

It recommended that environmental equity and justice issues be incorporated into land use planning and zoning decisions by local governments and be considered by each state agency as an element in their plans.

The state then abolished the commission. No changes were made to any laws. No new laws were passed. Everything stayed, as the Talking Heads used to sing, “same as it ever was.”

Thus, all these instances of environmental racism are perfectly legal under state law. That’s the message I would deliver to all the teachers should I be invited to speak. I think that’s the kind of information the task force would want them to hear.

Now let’s all rise and belt out “Lift Every Voice and Sing” — that is, if you can do it without too much cough-cough-coughing.

This piece was republished from the Florida Phoenix.