A Warden Tried to Fix an Abusive Prison. He Faced Death Threats.

He was tasked with ending abuse at a federal penitentiary, but he says his own officers and the Bureau of Prisons stood in the way.

By Christie Thompson, Beth Schwartzapfel, and Joseph Shapiro

On November 15, 2023

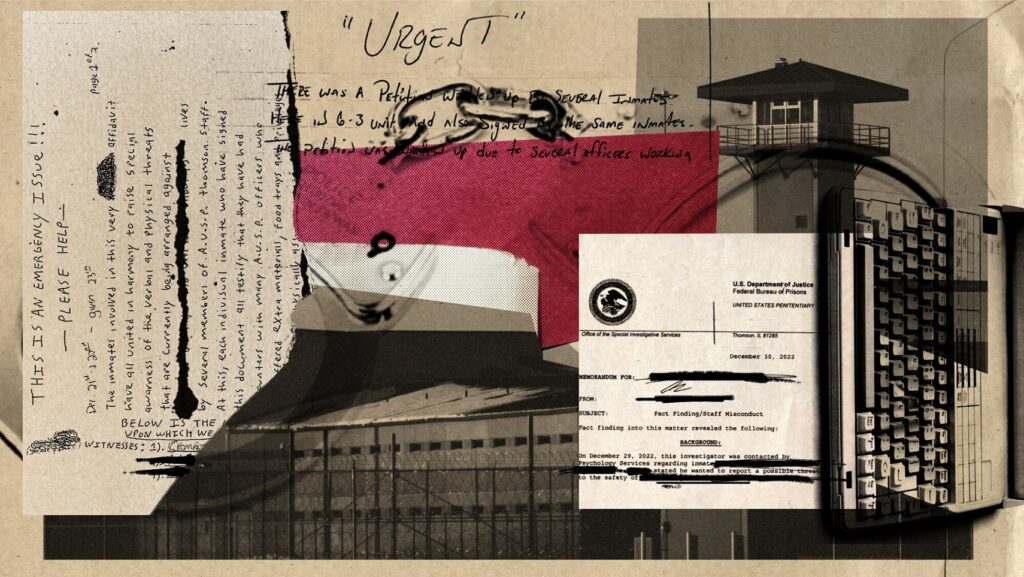

The handwritten letter arrived days before Christmas 2022. “THIS IS AN EMERGENCY ISSUE!!!” it began. “PLEASE HELP.” Signed by 14 people incarcerated in one of the highest security federal prisons in the country, the letter was an urgent warning for prison officials: Several corrections officers were trying to bribe prisoners to attack the warden and one of his captains.

Three men said officers “offered to poorly tighten their hand restraints” during the warden’s walk-through “so that the inmate can easily slip his hand restraints and carry out a physical assault,” according to the letter. Guards had offered the men extra food trays and other favors, and promised not to injure them after the attack. The men wrote that officers were angry about changes by the new warden.

Thomas Bergami had taken over the Thomson penitentiary in western Illinois nine months earlier — tasked with fixing a prison where five prisoners were killed in recent years and where more than 120 people have reported serious abuse.

A second letter delivered soon after the first made similar claims, and said that officers suggested someone stab the officials. An investigator from the Bureau of Prisons interviewed some of the men who signed the letters and found the information they provided “fairly consistent,” according to his report. But because “none provided specific dates or times of the allegation,” the agent wrote, he “could not confirm nor refute” their accounts. Bergami, who retired this summer, said in an interview that the officers on that unit, who had been taken off their posts, returned to work days later.

“When the regional director called me and said, ‘Well, they looked into it and put those guys back on their post,’ I’m like, ‘Are you freaking kidding me right now?’” Bergami said. “My staff were saying to stab me and the captain. I’ve got to worry about our safety.”

Bureau officials did not respond to questions about the letters and the investigation. The explosive allegation is among several incidents that Bergami and his former top deputy at Thomson recalled in recent interviews with The Marshall Project and NPR, detailing what they described as a culture of abuse and impunity at the prison.

Their accounts, together with interviews with other Thomson employees and dozens of internal bureau documents reviewed by the news organizations, depict a prison where officials were unable to fire guards they considered dangerous, the officers’ union resisted management’s efforts to hold staff accountable, and other managers at the agency undermined their efforts to make change.

Bergami said he realized from his first day at Thomson, where more than 1,400 men are held, that the prison had an “enormous problem with inmate abuse,” including falsifying charges against Black prisoners and keeping men in painful restraints for days. The attitude of staff there, he said, was “the worst I’ve seen in 31 years” working in corrections.

When Bergami arrived, Thomson was home to the “Special Management Unit,” a program meant for the most disruptive people in federal custody. But the unit was racked by violence: The Marshall Project and NPR published an investigation last year into multiple deaths at the prison and accounts of extreme mistreatment.

M. SPENCER GREEN/AP

The Bureau of Prisons closed that unit in February, concerned over the misconduct there. The prison has since been converted to a low-security institution. But according to current staff and families of people incarcerated there, the abusive environment persists.

In a statement, Randilee Giamusso, a spokesperson for the bureau, said the agency is working to address employee misconduct, and that “developing meaningful change throughout the agency is not something that happens in a moment.”

Jonathan Zumkehr, president of the union that represents officers at Thomson, rejected allegations of mistreatment there. “I will disagree 100%. That didn’t happen,” he said. He criticized Bergami for “blaming staff” for incidents that happened under his leadership. “We have great staff at Thomson,” Zumkehr said. “If anybody committed any of those horrible acts, we want them held accountable.”

Damon Jackson was one of the men who signed the first letter warning Bergami. In a phone interview, Jackson recalled officers offering an MP3 player or extra food, telling his cellmate, “If something happened to the warden, they gonna take care of him.” After the letter, Jackson said the investigator spoke to a few people who signed it, but not to him. “We never heard nothing back after that,” Jackson said.

Jackson and the others were moved to other prisons after the Special Management Unit closed. He said officers “felt like the warden was too soft, was too pro-inmate. They wanted to get him out of the way so they could continue beating inmates and run the prison the way they wanted to run it.”

Bergami was the warden of a medium-security federal prison in New Jersey when bureau officials asked him to run Thomson. He hired Denny Whitmore, another 30-year veteran of the federal prison system, as his associate warden. When they arrived at Thomson in Spring 2022, they were shocked by some of the staff’s practices.

Agency policy prevented Bergami and Whitmore, who also retired this summer, from speaking publicly about the prison without authorization while they worked there. They said they felt that reporting the abuse at Thomson to their superiors at the agency blocked their own advancement opportunities, so they chose to retire instead.

Both said when they arrived they were distressed to see officers walk people in shackles backward down the stairs, one officer on each arm, and a third controlling the prisoner’s head. Bergami wrote to his superiors that he had never seen that method in any operations manual and that he found it dangerous and unnecessary. Bergami and Whitmore said staff also would move prisoners across the yard in freezing winter weather with no shoes or coat on.

They also saw guards routinely use “black box” handcuffs, meant only for the most dangerous transfers, to move people in low-security custody. With this device, the chain connecting the cuffs is covered by a hard plastic box that further restricts movement.

Bergami said he ordered staff to stop using the black box handcuffs, and to change how they transferred people. But some officers pushed back. One officer “was talking about how he was going to use the black box anyways, even if not authorized by the administration,” a staff member wrote in a June memo that Bergami provided to The Marshall Project and NPR. “I observed [the officer] to say, ‘that f—– motherfucker in charge,’ when discussing Warden Bergami,” the memo continued, using a gay slur.

From the beginning, Bergami clashed with Zumkehr, the union president, who Bergami said encouraged staff to flout bureau policy. Multiple memos and emails detail their antagonistic relationship.

In interviews with local media, Zumkehr said that Bergami’s “ever-changing policies and procedures” put staff at risk, and called for his firing. “In recent months we have had an abundance of serious incidents which took place under the Thomas Bergami leadership,” Zumkehr wrote in a July 2022 letter, saying that managers were “placing the hard-working staff in limbo.”

Bergami said staff also frequently used “four-point restraints,” a tactic meant as a last resort. People in four-points are splayed spread-eagled, with each of their limbs shackled to a corner of a bed. People incarcerated at Thomson reported being held this way for hours — or days — at a time. Many said they weren’t fed or allowed to use the bathroom, forcing them to lay in their own waste. “It’s really akin to a torture chamber,” one attorney told The Marshall Project and NPR.

Bureau policy says four-points are meant as a rare and short-term intervention, when they are “the only means available to obtain and maintain control over an inmate.” The warden has to approve their continued use. Concerned the restraints were being overused, Bergami said he began requiring staff to videotape checks on people who were chained down. When he watched some of those recordings, the men in shackles were compliant — making the four-point restraint unnecessary, Bergami said.

“He was cool as a cucumber,” he said of a prisoner. “It didn’t add up.”

Zumkehr said that staff were following bureau rules when using four-points. “How can you say that my staff are torturing inmates when they’re following the bureau policy?” he said.

Some restraints were applied so tightly they left scars, which prisoners called “The Thomson tattoo.” Bergami asked medical staff for a count of how many people there had this injury. They found over 90 people with the scars.

In a September congressional hearing, U.S. Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois called the conditions at Thomson “stunning” and “sickening.”

Bergami said he tried to fire at least three officers who were found by internal investigators to have abused people in their custody, but his superiors blocked him each time. One of the officers Bergami said he tried to fire was named in two separate lawsuits alleging he slammed two prisoners’ faces into the concrete floor, knocking one unconscious, according to court records. Neither person suing had an attorney, and both cases were dismissed. Efforts to reach the officer were unsuccessful.

That officer was “recommended for termination” by employment personnel at the bureau and by Bergami, according to the former warden and Whitmore. But they said other agency officials overruled the recommendation. The Bureau of Prisons confirmed that the officer is still working at Thomson but declined to answer other questions about the case. Another staffer who Bergami said he tried to terminate is now working at a different federal prison.

The bureau’s regional director for Thomson, Andre Matevousian, declined to comment. Giamusso, the bureau spokesperson, said, “the vast majority of our employees are hardworking, ethical, diligent corrections professionals, who act with integrity daily and want those engaging in misconduct to be held accountable.”

JOSEPH SHAPIRO/NPR

Bergami and Whitmore said they also tried to fire an officer who they saw on video throwing away prisoners’ mail, a possible felony. The agency also overruled them in that decision, they said. The bureau did not respond to allegations of staff destroying mail.

“How do you root out the bad apples if you’re not allowed to terminate those who have been recommended for termination?” Whitmore said.

The two former Thomson officials and a current prison employee said the attitude among many guards was reflected by a group who refused to wear their issued uniforms. These officers opted instead for black T-shirts, many with the union logo or the skull logo of The Punisher — a vigilante comic book character popular with far-right groups. They called themselves “The Black Shirt Mafia.”

Zumkehr said he had never heard staff use that phrase, but that many staffers wore black union sweatshirts, which he said Bergami initially approved.

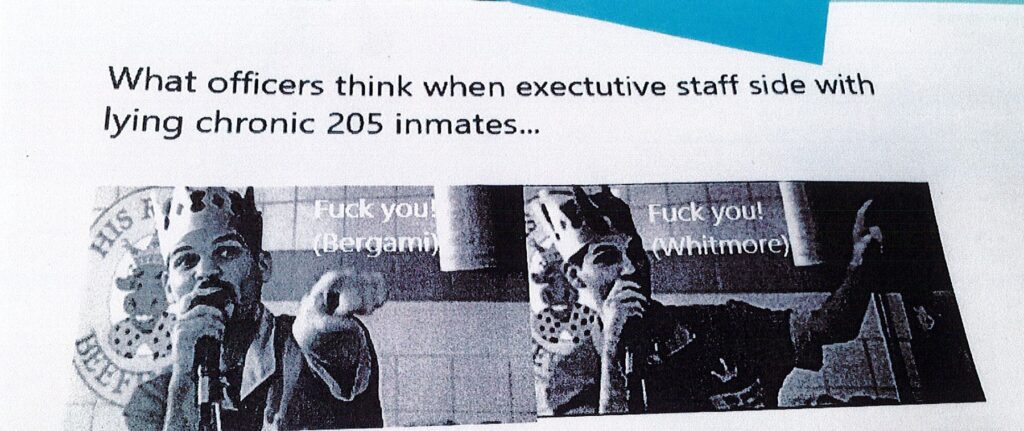

Thomson officials and the union also clashed about what staff referred to as “205s”: incarcerated men who masturbated in their cells in front of officers as a means of sexual harassment. Staff members told the union that prison officials were failing to protect them from such assaults, according to a report from a site visit by bureau employees and national union staff. Union officials told local media that there were over 500 instances of this in 2021. This summer, the union successfully lobbied to pass a state law in Illinois that will make repeat “lewd exposures” in prison a felony offense.

COURTESY OF DENNY WHITMORE

Bergami and Whitmore said many of these reports were falsified as an excuse to punish Black prisoners and segregate them on a specific tier for men accused of such acts. Other Thomson employees, who spoke to The Marshall Project and NPR, also said some staffers made up incidents. The site visit report also noted that “inmates of color are terrified of the correctional officers.” Current and former Thomson employees said that racism was rampant at Thomson, directed toward both the incarcerated and staff members of color. According to the bureau, roughly 83% of Thomson staff are White.

In a statement, Giamusso, the bureau spokesperson, did not respond to specific questions about the sexual misconduct allegations or the claim that they were sometimes falsified. She said all staff receive mandatory diversity management training every year.

Zumkehr denied that staff members made up incidents, and said that if they did, Bergami should have referred those staffers for misconduct investigations. “When the warden is saying all staff are faking it, we’re encouraging staff not to report this now,” he said.

At the Senate judiciary hearing in September, bureau Director Colette Peters spoke about the decision to close the Special Management Unit at Thomson, citing abuse and misconduct. “I too, hadn’t seen anything like that in my 30-plus year career in corrections,” she said.

Peters also told senators that officers who engaged in abuse were facing administrative and criminal investigation. Giamusso, the bureau spokesperson, said the agency is “actively rooting out and addressing employee misconduct,” but did not provide details on the status of such investigations.

Staffers and families of people at Thomson said the mistreatment continues. Several said the facility still felt like a maximum security prison. They said their loved ones have been called racial slurs, denied visits or held in solitary confinement for months with little justification.

Bergami said there’s only one way forward: shutting Thomson down entirely.

“We don’t want anyone to ever have to go through what we went through. More importantly, the inmates that are housed under our care are still being abused,” he said in a recent interview. “Where is the accountability?”

This piece was republished from The Marshall Project.