Almost all Louisiana death row prisoners ask John Bel Edwards to spare their lives

By James Finn

On June 13, 2023

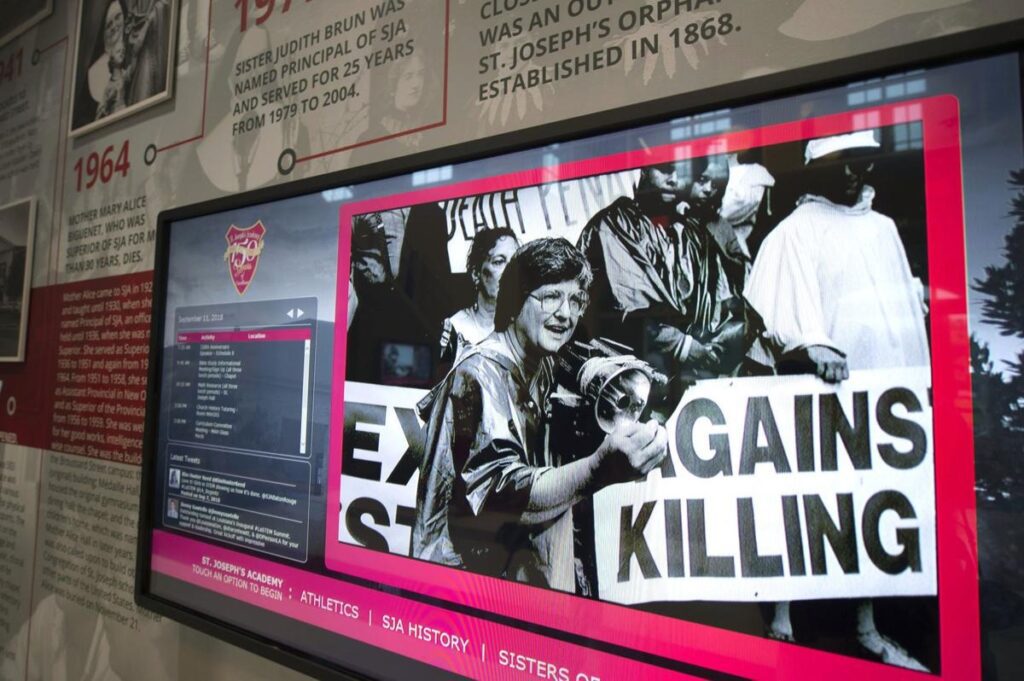

Edwards recently said he opposes the death penalty and believes it should be banned in Louisiana.

Nearly all of the 57 people on Louisiana’s death row have asked Gov. John Bel Edwards to spare their lives, a historic request made after Edwards broke his silence on how he views capital punishment and pushed lawmakers to outlaw the practice.

A total of 51 clemency applications filed Tuesday morning with the Louisiana Board of Pardons and Committee on Parole do not ask Edwards to free all of those death row prisoners. Instead, the documents ask him to soften their sentences to life-in-prison — the only commutation available to people sentenced to die.

“Looking at these cases collectively makes it clear that the system is fundamentally broken,” said Cecelia Kappel, executive director of the Capital Appeals Project, which led a group of attorneys who represent death row prisoners in filing the requests. “These applications show that the same problems of racial disparity, intellectual disability, severe mental illness, trauma, innocence and others repeat over and over in Louisiana’s death penalty cases.”

Edwards granting the requests would mark a historic turn in the way Louisiana regards the death penalty. An avowedly Catholic Democrat from a long line of sheriffs, Edwards has long kept mum about his thoughts on the practice. He only recently came out in full-throated support of abolishing capital punishment, in the waning months of his governorship.

Asked how the governor would respond to the appeals, Edwards spokesperson Eric Holl said only that applications recommended by the Board of Pardons and Committee on Parole are reviewed “on a case-by-case basis before a final decision is made.”

A shortage of lethal injection drugs has put a halt to capital punishment in Louisiana; the state last carried out an execution when Gerald Bordelon was voluntarily put to death in 2010 for the murder of his 12-year-old stepdaughter, Courtney LeBlanc. Prior to Bordelon’s execution, the state had not put anyone to death since 2002.

Even as the drug shortage has paused executions in Louisiana, they have continued in other states. Texas, Missouri, Florida and Oklahoma have all put people to death this year, according to data tracked by the Death Penalty Information Center. In some states, officials have moved to reinstate old execution methods — such as firing squads — to address the lack of lethal injection drugs.

Attorney General Jeff Landry, an ardent death penalty supporter who is running for governor, said he would oppose the clemency applications as they move through the process. His office could do so by submitting arguments against the requests to the pardon board.

“I oppose clemency for all of these offenders who were given valid death sentences by juries of their peers,” Landry said in a statement. “My office will formally oppose their applications.”

Governors have granted only two clemency requests from death row inmates since Louisiana instated the death penalty in the 1970s.

The first was for Ronald Monroe in 1989, whose guilt was doubted by then-Gov. Buddy Roemer. The second was for Herbert Welcome in 2003; Gov. Mike Foster concurred then with the Pardon and Parole Board’s recommendation of clemency after the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Atkins v. Virginia, which found that executing people with intellectual disabilities violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment.

Yet Louisiana newspaper and court records are replete with recent stories of men, often Black, who are sentenced to die, but who have later been found innocent and ordered freed by the courts. A disproportionate three-quarters of Louisiana death row prisoners are people of color, according to the Capital Appeals Project.

The clemency applications filed Tuesday with the pardons and parole board detail a range of mental health conditions the death row prisoners have. Among those requesting clemency is Antoinette Frank, the only woman on death row in Louisiana. Frank is housed at the Louisiana Correctional Institute for Women in Baker, while the men on death row are held at Angola.

Attorneys are requesting life sentences even in a few cases where they offered evidence of the prisoner’s innocence in the clemency requests.

Their fates now lie in the hands of Edwards and the board of pardons and parole. The board’s members — all of whom are appointed by Edwards — will weigh the batch of applications individually, decide whether to grant a hearing and then pass their recommendations on to the governor, said Francis Abbott, the board’s executive director.

He said the board would give 60 day notice to victims, district attorneys, district court judges and law enforcement agencies involved in each case before it conducts public hearings.

“The process from application to hearing can take up to a year and includes a thorough investigation,” Abbott said.

During his seven years in the governor’s mansion, Edwards shied away repeatedly from expressing his views on the death penalty. State lawmakers have also repeatedly refused to get rid of the death sentence during that time.

The closest they came to doing so was in 2019, when two bills on the issue made it to the floors of the House and Senate. At the time, Edwards, who was running for re-election as the Deep South’s only Democratic governor, refused to discuss his stance on the matter, saying only that he would uphold state law.

The issue also didn’t factor into discussions about criminal justice reform in 2017, when Edwards helped craft a sweeping bill package aimed in part at reducing Louisiana’s highest-in-the-world incarceration rate. The reforms sailed through the Legislature with strong bipartisan majorities and became a signature accomplishment of Edwards’ term.

Edwards finally broke his silence in March. He supports abolishing executions as part of his “pro-life” values, he told attendees of a talk at Loyola University in New Orleans. Attributing his stance to his Catholic faith, Edwards said it has been “fortuitous” for his governorship that a shortage of lethal injection drugs paused executions in the state.

“The death penalty is so final,” Edwards said then. “When you make a mistake, you can’t get it back. And we know that mistakes have been made in sentencing people to death… The only people (on death row) we know who were innocent are those who’re released before they’re killed.”

A few weeks later, Edwards in his state-of-the-state address called on the Legislature to pass a bill sponsored by Rep. Kyle Green, D-Marrero, that would have abolished the death penalty.

That effort proved ill-fated: The bill died near the end of the Legislative session in a House committee that had recently become more conservative, part of an effort by House Speaker Clay Schexnayder to address surging crime.

The clemency requests filed Tuesday are supported by the Archdiocese of New Orleans.

“We join in support of the request to Gov. Edwards to commute the sentences of those on death row to life without parole,” Archbishop Gregory M. Aymond said in a statement. “At the same time, we continue to pray for the victims and their families and for their healing and for an end to violence in our communities.”

This piece was republished from the NOLA.