American classrooms need more educators. Can virtual teachers step in to bridge the gap?

By Alia Wong

On September 1, 2023

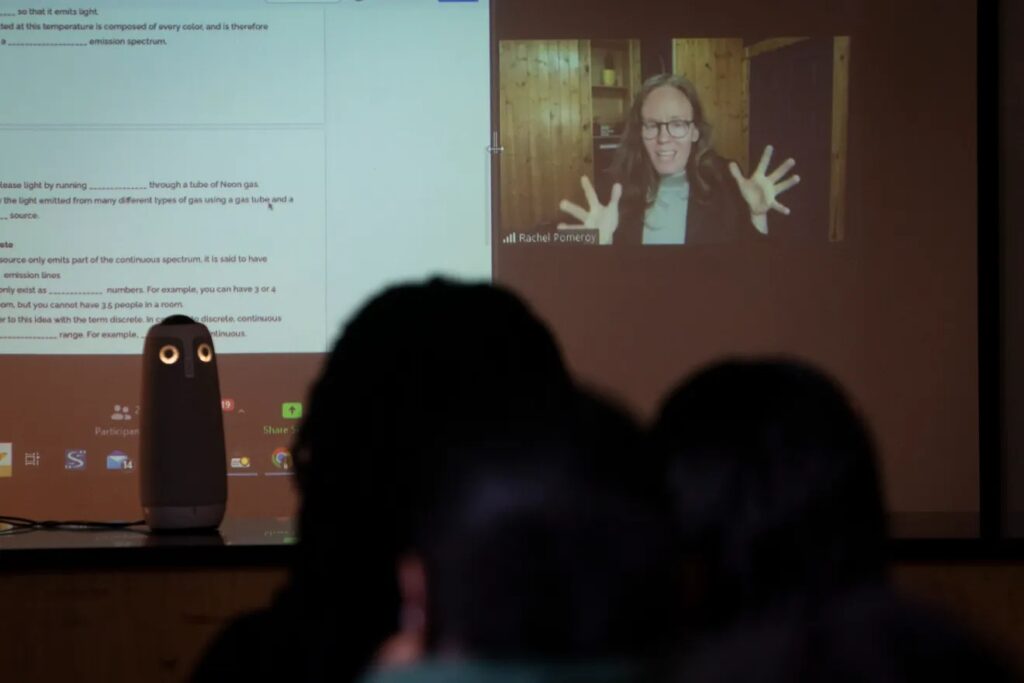

WASHINGTON – Rachel Pomeroy tries to be as engaging as one can be when reviewing physics concepts with high schoolers on the eve of summer vacation.

The veteran teacher projects images of an “open” sign and an incandescent bulb and a sunset, instructing the 20 or so teens to judge whether the light the objects emit comprises multiple colors. She later plays a humming noise, and then another. “Doubt you can hear the difference,” she says. Separately, the noises sound identical. But when Pomeroy plays the files at the same time, a pulse erupts every few beats. That, she explains, is constructive interference.

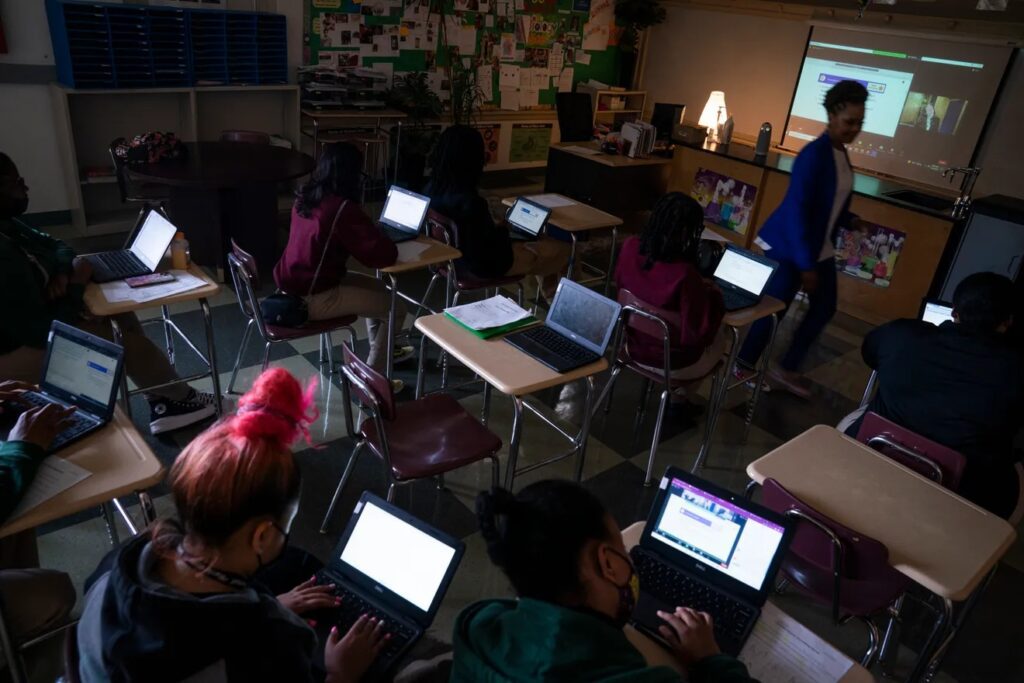

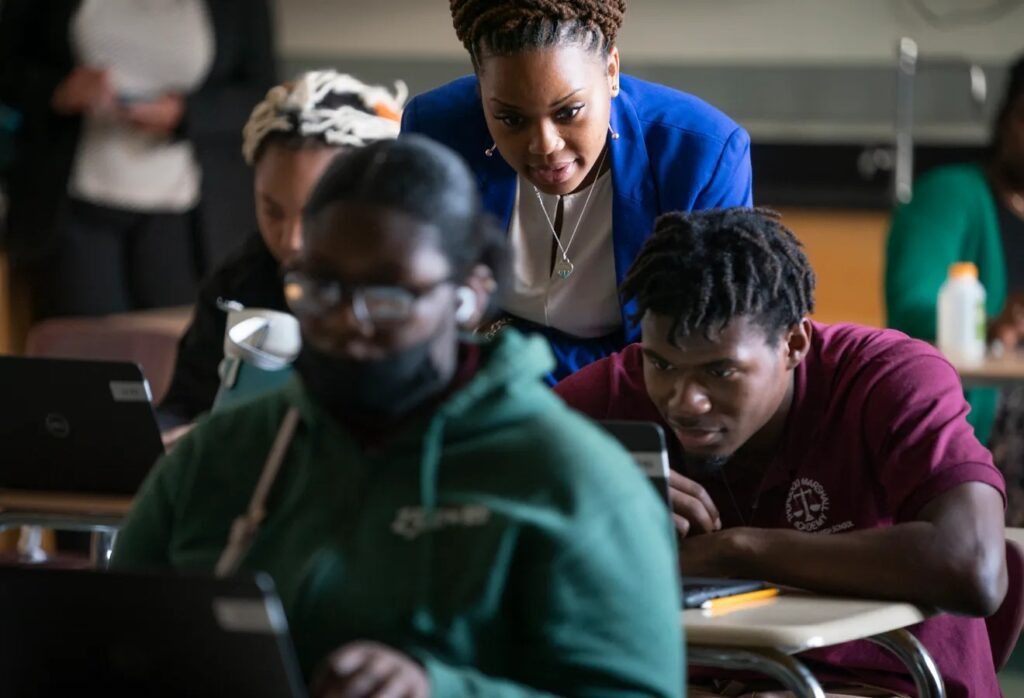

Pomeroy’s savvy use of internet tools and activities aimed at making the science tangible seem to have their desired effect, at least on some. A dozen or so students earnestly participate in the exercises, using different colors to label their responses and shooting their hands up when they know an answer. Others appear bored or distracted or simply tired on this early Wednesday morning in May – several have their heads on their desks, a few check their email. One strolls in 20 minutes late, rubbing her eyes.

This scene out of Thurgood Marshall Academy in southeast Washington feels, in many ways, like your typical physics class. What’s different about this class, though, is that Pomeroy isn’t physically there. She’s roughly 1,000 miles and four states away, teaching virtually from her home in Marquette, Michigan.

Three years ago, as the first full COVID-disrupted school year kicked off, kids across the United States found themselves forced to learn from teachers on a screen. The result was, by and large, disastrous. Scores of students are still struggling with knowledge and skills expected of someone at their grade level – losses largely attributable to the virtual instruction necessitated by the pandemic.

Yet, with lots of schools unable to hire certain teachers, virtual instruction in the form of remote educators like Pomeroy has grown in popularity. Students gather in-person and learn from a teacher far away, typically alongside a second adult who helps manage the classroom and handle everything from technological glitches to rowdy behavior.

Most observers, including some providers of these very services, agree this isn’t ideal. Students with virtual teachers often say they like the classes but would prefer the instruction to be in-person. School leaders and scholars worry about the services’ financial costs – and the academic ones. Some critics describe the trend as, to borrow Columbia University education Professor Samuel Abrams’ words, indicative “of a country that’s lost its way.”

But at a time when schools in some locales are short teachers in key disciplines, advocates say virtual teachers are necessary to ensure kids of all backgrounds have access to coursework that can propel them into their dream college or career. It is, they argue, an inevitable if uncomfortable solution to a problem that – given generational shifts and post-COVID circumstances – will only get worse before it gets better. At least it’s better than a long-term substitute, some say.

But will schools’ embrace of this model, however cautious, allow systemic problems plaguing the teaching profession to fester?

Many communities don’t have enough teachers

The virtual instruction teachers like Pomeroy provide is different from the remote learning associated with the pandemic. The latter was haphazard and abrupt. This is deliberate and structured – Pomeroy and her counterparts are well-versed in the technology, and they work in tandem with in-person adults who ensure the students stay on task.

Pomeroy started teaching students at TMA, a charter school, in January, after some staff departures left the school without anyone to teach physics – a graduation requirement at the college-prep school.

It was one of countless schools nationally without enough staff to teach critical subjects, a problem that persists to this day. Hundreds of thousands of teachers have left K-12 education in the past few years. A growing body of data suggests states have seen an uptick in the percentage of departing teachers compared with pre-pandemic times. Last year, nearly half of schools participating in a national survey reported at least one teacher vacancy.

Distance learning hit disadvantaged mostThe teacher shortages are just piling on.

Filling these vacancies can feel like “you’re looking for a unicorn,” said Shara Hegde, the founder and CEO of a San Jose, California, charter network called Alpha Public Schools. “You’re looking for a teacher with, for example, great physics content knowledge, who is also great with students, who wants to teach in a low-income community – with kids who may not be coming into that physics class with all the upper-level math they may need to excel in that class.”

“How are we promoting equity if kids are not learning physics?” Hegde said.

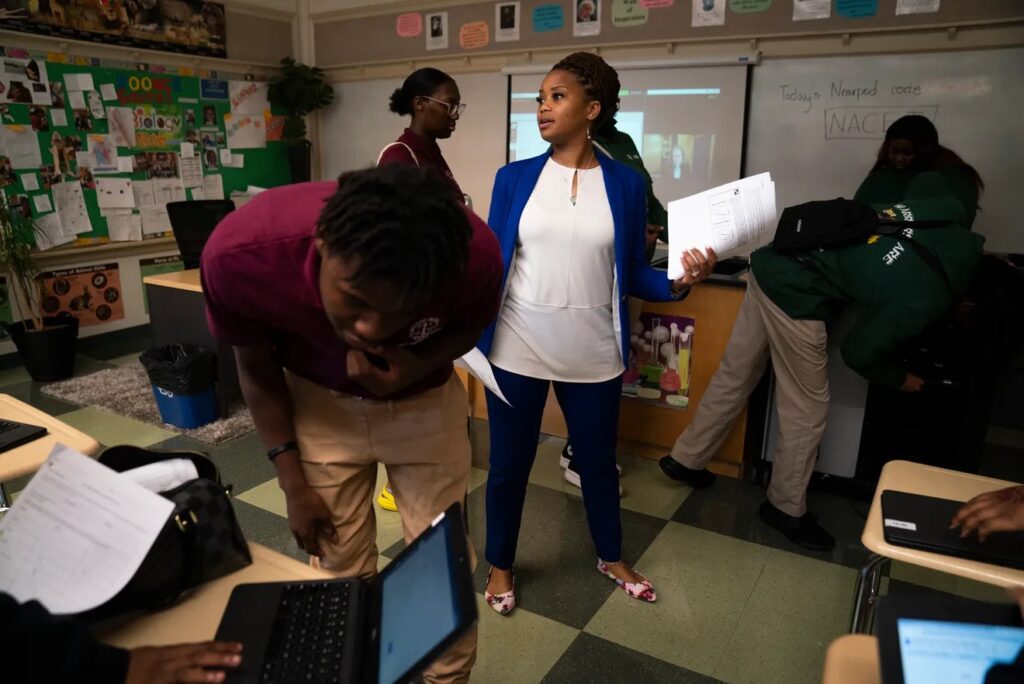

Both TMA and Alpha contracted with Coursemojo, the for-profit company through which Pomeroy teaches, in part as a sort of stop-gap solution. And as far as emergency alternatives go, TMA’s Tara Allen said, Coursemojo has exceeded expectations. Teachers and students interact in real-time, and the software used for lessons has all kinds of fancy tools that allow educators to track individual kids’ progress. “If you were blindfolded, you’d think there are two teachers in the room,” said Allen, a veteran math teacher who now serves as the school’s director of teaching and learning, “and that it was still just a normal class going on.”

Ronniesha Thomas, a senior at the time, agreed that her physics class feels similar to her more traditional ones. But she also stressed that learning through a screen can be difficult after long stretches. “We just have to push through sitting, looking at a computer,” said Thomas, who’s now beginning her freshman year of college.

She appreciated that Pomeroy incorporated various “activities and exercises that can take us away from looking at the computer screen.” They did laboratory experiments and group projects.

Shyre Brown, another TMA senior, said she’s someone who needs a lot of guidance when she’s learning. “I need a person that can come beside me and be like, ‘Oh do you understand?’ or be, like, asking me questions and pushing me,” Brown said.

That there is, at a minimum, one teacher in the room is what allows the Coursemojo model and ones like it to work, company and school leaders said. These adults are often paraprofessionals or aides or teachers-in-training who don’t have the requisite training to lead a physics class.

Back in D.C., weaving from desk to desk as Pomeroy delivered lessons, was learning coach Samantha Koonce-Gaines. Koonce-Gaines is the science department chair but her specialty is biology. Her days are already packed with teaching other classes and other responsibilities as chair; as a learning coach, she doesn’t have to do all the lesson planning and grading and other tasks that come with leading a class.

The companies that provide this teaching try to make it as immersive as possible, with the educator leading the class in real-time from a large screen projected at the front of the classroom as well as on students’ laptops. Increasingly, Coursemojo has prioritized more in-person interactions among students through small group work, for example.

In focus groups with students last year, participants said they really liked their online instructors as well as the content, but many said they wished the teachers were in-person. Several TMA students pointed to Koonce-Gaines as a critical aspect of the physics class.

Does teaching through a computer allow for more work-life balance?

Pomeroy started teaching more than a decade ago in a traditional brick-and-mortar school. She loved science and math, and working with young people. What drew her to the opportunity to teach virtually at Coursemojo was, she said, her excitement about the possibilities of online education when done right.

“As educators, change is so slow. We often deal with the same problems year after year after year. At this point in my career, I was excited to tackle a different problem. To really look for a challenge that was different than the challenges I’d been experiencing so many years face-to-face,” she said. “I was excited to figure out what ways might there be to increase online learning to address a problem – not just as a Band-Aid but as a way to really do education well.”

Beyond the opportunity to be part of something innovative, however, are the practical benefits. While there’s no such thing as a 40-hour week in teaching, Pomeroy said, the profession is so much more manageable when done remotely.

“Teaching is an incredibly time-intensive endeavor,” she said. “But there’s an element of flexibility (in online teaching) that makes those hours more comfortable.” The mom of two can throw in a load of laundry while grading papers, for example. “It makes it more comfortable to do what you love in a career you’re passionate about.”

The feasibility of work-life balance – or some semblance of it – is one of the key value propositions of this model, said Shaily Baranwal, the founder and CEO of Elevate K-12, a for-profit company that provides virtual teaching.

“Teachers are leaving the profession because they want flexibility,” Baranwal said. “They want to work from home, they want to pick their own hours, they want to work from anywhere.” When surveyed by the company, teachers who work with Elevate K-12 cite these precise reasons when explaining why they made the switch.

They are also drawn to the relative lack of bureaucracy at such virtual teaching companies. Jessica Flemming, a Houston-based math teacher with Elevate, primarily chose to become a virtual educator for logistical reasons. She and her family were preparing to move out of state, and she wanted to be able to continue working without having to go through the licensing process all over again.

But Flemming liked that she could pick and choose what she taught, ensuring a diverse spread of disciplines while prioritizing the subject – calculus – that she was most passionate about making accessible to students.

“Truthfully, that’s what this new generation demands,” Baranwal said. And in her view, making the teaching profession attractive to this new generation is one of its most important feats. Elevate’s teachers are contractors, meaning they are not salaried employees.

Education ‘is a social enterprise’

Many students, Pomeroy said, feel more comfortable interacting with others virtually. She pointed to the lifelong relationships she formed with students despite never meeting them in-person, and to the way they bonded over their differences. She reflected on the time she told her TMA students that she fell on the subway her first time visiting D.C., how they burst out laughing and never let her live it down.

But can a virtual teacher really replicate all the ineffable qualities that an in-person one can offer? Can a virtual teacher easily notice if a student is crying or sick? Can they make eye contact and provide real-time feedback in a way that’s tailored to the student’s individual needs?

There’s not yet a lot of data that can perfectly compare the academic achievement of students taught by virtual educators with that of students who received in-person instruction. Coursemojo pointed to grades and test scores, but lots of factors can muddy the picture, including the virtual educators’ own biases.

Harvard education professor Susan Moore Johnson is one expert who doesn’t buy all the hype. Johnson has observed and studied teaching for more than four decades, and said many of the ingredients found in effective learning conditions aren’t present in this model. “Good teaching, learning, schooling is a social enterprise,” she said. The work needed to catch kids up post-pandemic “won’t happen when someone is beaming in then going onto another school, another classroom.”

Anecdotal evidence shows how the model can go awry. There have been reports of students leaving classrooms mid-way through a lesson, and of parents not knowing until much later that their children were assigned virtual teachers.

Then, of course, there is the emerging research on pandemic-era remote learning. Data reveals teachers simply weren’t as effective in virtual classrooms. Critics told USA TODAY it’s impossible to ignore those findings when evaluating the outcomes of virtual teachers.

Teacher shortages:To fill vacancies, schools turn to custodians, bus drivers and aides

An expensive solution

That providers such as Coursemojo are for-profit companies is one of the model’s fundamental flaws, said Columbia’s Abrams.

“This is American business, … a way for investors to make money,” said Abrams, who directs the National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. He has been following the virtual teachers trend since ed-tech companies started broaching it more than a decade ago. “They found that market because there’s a state failure to pay teachers appropriately and treat them as professionals. And they’re taking advantage of state failure.”

While the virtual programs they help schools address vacancies, though, they aren’t necessarily a more cost-effective option. In fact, the virtual teacher model used at Alpha – which in addition to the educator and learning coach includes other virtual support staff – is double the cost of a traditional in-person educator. For most of Coursemojo’s other partners, having a virtual instructor costs between 20% and 40% extra, according to the company.

“Was it very, very expensive for us? Absolutely,” Hegde said. “That’s the drawback here – it was definitely not a nice, sustainable model for Alpha. But did we do it because it was the right thing to do and equitable? Absolutely.”

The 74, an education news outlet, in a recent analysis of K-12 purchase orders, found that individual districts are now spending thousands and sometimes millions of dollars on this model.

Abrams suggested these options are concentrated in low-income schools and almost nonexistent in wealthier communities. While national data isn’t available, a review of anecdotal evidence indicates that’s indeed the case. Most of the students served by Elevate K-12, for example, live in low-income communities. They tend to be in urban and urban-fringe neighborhoods or rural areas, according to the company’s data.

Investing in the teaching profession – not ed tech

Dacia Toll, a former teacher who co-founded the company that merged into Coursemojo, said its virtual instructor model needs for-profit backing given the high up-front costs of developing technology and curriculum. She doesn’t pretend ed tech is a cure-all. “Most online learning is bad,” she said. But that’s largely because it tends to be asynchronous – a teacher recording and uploading a lesson with students participating and completing assignments at their own pace. Much virtual instruction is also less rigorous than it would be in-person, she said.

Coursemojo’s model, Toll said, tries to address those challenges head-on. A majority of its teachers, unlike those working for some of the other players in the industry, are full-time. The company, whose educators have eight years of teaching experience on average, also puts a lot of emphasis on coaching and training. Given both current shortages and the chronically unequal distribution of quality teachers and funding, she said, virtual educators are a necessary option to ensure all kids get the instruction they deserve.

In addition to addressing widespread vacancies, Coursemojo aims to expand access to more niche or advanced courses – like American Sign Language and coding – that many schools can’t offer on campus because there isn’t enough of a critical mass.

“We’ve got to be open to new models,” said Richard Culatta, CEO of the International Society for Technology in Education, who’s argued for taking a balanced approach to ed tech. At the end of the day, whether the instruction happens virtually is somewhat irrelevant. Rather, he said, “by far the biggest factor … comes down to the people side.” How are the educators trained and how are they delivering on their vision for the class? How are they fostering human interactions? How are they individualizing lessons based on students’ needs?

“Technology can be the most powerful tool for closing opportunity gaps in learning,” Culatta said. “But at the same time it’s also probably one of the largest craters of those gaps if used inappropriately.”

This piece was republished from USA Today.