At New Mexico’s biggest jail for children, toilets and staff are lacking — but strip searches are common.

By Joshua Bowling

On July 19, 2023

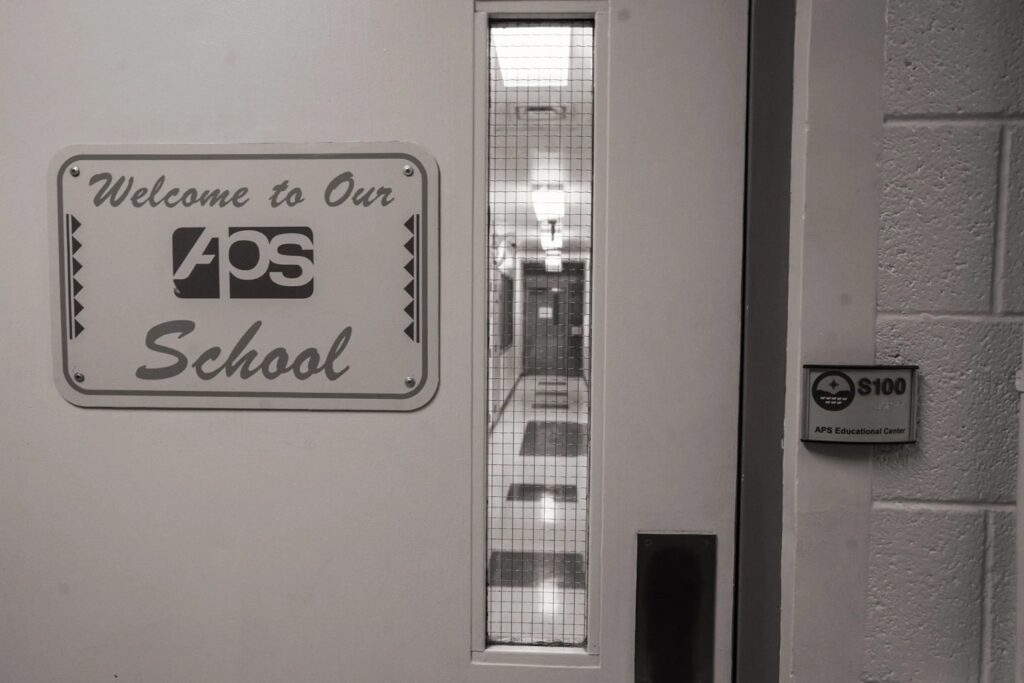

The décor inside the Bernalillo County Youth Services Center (YSC) is more in line with the children’s wing of your local library than a jail built for kids. The walls and furniture are painted in bright colors and classrooms line a hallway just a short walk from a common room filled with therapeutic rocking chairs. Out back, the children — strictly referred to as “residents,” never inmates — are encouraged to tend a communal garden or navigate a multi-story rope obstacle course — the tallest of its kind in all New Mexico, according to the county.

But behind the vibrant colors and soothing rocking chairs, the state’s largest juvenile detention center suffers from the same severe understaffing that plagues institutions across New Mexico. Inside, children between the ages of 12 and 17 are routinely subjected to strip searches, held for weeks in cells without toilets, and left with only a thin plastic sheet to block out the glare of hallway lights that never turn off. Girls face particularly harsh conditions, often placed in what advocates call the equivalent of solitary confinement.

In the words of YSC Director Michael Ferstl, the facility was once “a five-star hotel” that now resembles “a dirty car that’s got snow from last winter still on it.” Persisting with that simile, he adds that it’s driven by a “very progressive” crew with their “hearts in the right place.” It just “needs to be washed.” Pushed harder, Ferstl acknowledges that “there’s roads we won’t go down because it’ll get even dirtier.”

Advocates and families say it’s already pretty dirty. They refer to chronic understaffing — a recent count found that nearly 70 percent of guard positions are going unfilled, according to the jail’s leadership. They refer to the fact that some of the children are held, sometimes for weeks, in temporary booking cells with no toilets or sinks. And they refer to the use of strip searches, a practice that’s been widely condemned as “state-imposed trauma.”

Alexis Pina, 21, says she was strip searched approximately 150 times over the course of her three-year stay in the detention center, where she was being held for second-degree murder. She recounted the process: Remove your socks and wiggle your toes. Take off your pants, underwear, bra and hair tie. Turn around, squat with your hands in the air and cough three times. When she refused to participate, she says, she was often locked in her cell until she consented.

Strip searches at the facility are supposed to be rare. In 2019, Bernalillo County invested in two machines — Cellsense, a contraband and cellphone detector, and Ionscan 600, an explosives and narcotics detector — aimed at searching inmates in a less invasive way. The Cellsense machine, which looks like a metal detector, just requires children to walk past it. If it beeps, that means it detected metal, potentially a weapon. The Ionscan 600 looks like a printer. After a jail employee swabs an inmate’s hands, the cotton swab is placed in the machine, which analyzes it for drug residue and trace amounts of explosives.

But these machines sometimes break and go offline for extended periods. Though officials decline to give specifics on how long or how often the machines crash, they acknowledge that strip searches are employed whenever that happens.

Pina says that in her three years at the facility it was a regular occurrence.

“Every time you leave the facility, they have to strip search you because the machine that they have to test whether or not you have drugs doesn’t work,” she says. “Conditions were so bad for me that I wanted to kill myself. I couldn’t handle it.”

While strip searching is still widely practiced in juvenile facilities across the country, lawmakers have taken steps to limit or abolish the practice. Some states, such as Virginia, have banned it outright.

“We have a criminal justice system that purports to be about supporting young people in growth and development, giving young people second chances,” says Jessica Feierman, senior managing director at the Juvenile Law Center, a national nonprofit based in Philadelphia. “If young people enter the facility and face a strip search, they can’t develop positive relationships with staff. They can’t feel comfortable. They may be traumatized. They may be triggered based on past sexual assault.”

Ferstl told Searchlight New Mexico that he is tired of outside experts — “all these professionals, all these psychologists, all these other people” — telling corrections professionals what to do. “Nobody has ever asked the kids. Nobody,” he says. “So guess what? I did.”

Seven years ago, Ferstl conducted what he calls a survey in which the “residents” were asked to check a series of boxes that best fit their opinions on strip searching. As shared with Searchlight, the survey included such questions as, “Do you agree with residents being strip searched after visitation/contact at the Youth Services Center?” and “Do you feel safer knowing that residents are strip searched at the Youth Services Center?”

The results, Ferstl says, were overwhelmingly positive: Kids here “wanted to be strip searched.”

A copy of the 2016 survey, as provided to Searchlight, shows that 44 youth participated. When asked if the questions were leading, or whether the children might have responded with what they considered to be the safest answers, Ferstl demurred. “I’m not saying it’s a scientific, well-thought-out survey,” he said.

Lack of staff, lasting impacts

While strip searches may pose one of the greatest concerns to juvenile advocates, families and local advocates point to understaffing as an equally important issue. And it is hardly unique to the Bernalillo County Youth Services Center. The Metropolitan Detention Center, New Mexico’s largest jail, has long been plagued by the same problem, as have all the state’s prisons. Schools and hospitals across New Mexico are also feeling the squeeze.

But advocates worry that the lack of staff at the Youth Services Center could negatively impact the long-term rehabilitation of troubled children and teens. Nationally and in New Mexico, there has been a growing emphasis on treating detained children as children — not as little adults — and ensuring they don’t miss out on important childhood experiences.

To that end, maintaining high levels of staffing is a critical factor in operating the 78-bed facility. On a recent day, according to Ferstl, 69 percent of the facility’s jobs were unstaffed: only 30 of the 96 youth guard positions were filled. Internal staffing reports show those employees routinely take on extended overtime shifts.

But during a recent tour of the jail by Searchlight, Ferstl denied that understaffing presented a dire problem; the facility, he says, consistently maintains a ratio of one guard to every eight inmates.

Families and former inmates insist that understaffing has been a driving force of friction within and without the facility’s walls.

Floyd Yazzie of Albuquerque says he has gone months without seeing his 16-year-old son, who was detained at the center for six months before being transferred to another state facility. Though in-person visitation is set at two visits per week, Yazzie and other members of the family were turned away for Christmas and the boy’s birthday — all because of understaffing.

“You look forward to, you know, your memories of Christmas and holidays with your family,” Yazzie says, “and they just rip that away from you.”

Girls may disproportionately bear the burden. Despite millions of dollars spent on renovating the 61-year-old facility, it is girls who are most often placed in cells without sinks or toilets. They are detained — sometimes for more than a week at a time — in booking cells, where the 24/7 overhead lights can only be blocked by a plastic sheet over a door window.

Feierman of the Juvenile Law Center says girls often find themselves “in the equivalent of solitary” confinement because they make up a smaller portion of detained youth: In the Bernalillo County facility, only eight of the 52 inmates are girls.

A 2012 report from the Georgetown Center on Poverty, Inequality and Public Policy says girls’ needs often go unmet in a “system that was designed for boys.” And research from the University of Texas at Austin, published in 2015, says girls are at greater risk than boys of serving longer sentences and having serious mental health needs.

When a child is locked up in a cell with no toilet, they have to wait for an escort to take them to a bathroom. If it’s a particularly understaffed day, they may have to wait for hours.

“I waited two and a half hours on Christmas Day to use the bathroom,” Pina says. “I wasn’t drinking water. I wasn’t eating my food, because I had to use the bathroom so often and they weren’t letting me out.”

Albino Garcia, the founder and executive director of the grassroots community organization La Plazita Institute and a member of the statewide Juvenile Justice Advisory Committee, echoes Feierman: He says Pina’s experience amounted to “essentially solitary confinement.”

Facility leaders flatly deny that accusation, saying it’s not solitary confinement because the youth are “never” confined to a cell for 22 hours or more per day, the widely-accepted definition of solitary. If they’ve been held in the booking cells, Deputy Director Stanley Gray says, it’s been as a quarantine measure to make sure they don’t inadvertently spread Covid-19 throughout the facility.

Officials also point to annual audits conducted by the state, which have found the detention center in “substantial compliance” with statewide standards. Those audits — which advocates like Pina and Garcia equate to little more than a rubber stamp — are typically made following scheduled visits by the state Children, Youth and Families Department. As a result, they say, there’s no element of surprise and detention staff have ample time to prepare.

“When there’s an audit happening, everybody knows,” Pina says, adding that the visiting auditors never once interviewed her.

Ferstl, however, says the setup is compassionate and done with the kids in mind. He points to the brightly colored walls, modern furniture and towering rope course. Prior to his leadership, the intake cell doors didn’t have so much as a screen mesh window.

Adding those — an idea he says he “got a lot of pushback on” — was done to comfort kids who are getting arrested for what “could be their first time.”

Understaffing at the YSC impacts law enforcement statewide

Twenty years ago, there were 14 juvenile detention centers spread across New Mexico. Today, there are four. In addition to Bernalillo County, they are located in Doña Ana, Lea and San Juan counties.

As these centers closed — a move generally celebrated by reformers — the Bernalillo County Youth Services Center contracted with surrounding locales to house criminally accused children. Under these agreements, 28 counties and Pueblos now send their arrested children to the Bernalillo County center, often an hourslong drive.

Despite that arrangement, in fiscal year 2022, the jail turned away 52 children for lack of staffing. That’s led to further strain on law enforcement agencies across the state, which are themselves acutely understaffed.

Las Vegas Police Chief Antonio Salazar told Searchlight that he often has as few as three officers working any given shift. Whenever a child is arrested, two officers must drive nearly two hours to the Bernalillo County detention center. Usually, they’re able to call ahead of time and see if the facility will book the child. But it hasn’t always worked that smoothly.

“There have been times in the past where the officers show up and they [the kids] are rejected,” Salazar said. Between the time spent driving there, sorting out the booking process and driving back to Las Vegas, the two officers could be off patrol for up to eight hours, he said.

This piece was republished from the Searchlight New Mexico.