Aurora is the first Colorado city under state oversight to reform policing. Two years in, how’s it going?

By Rachel Estabrook

On October 10, 2023

The announcement came suddenly, though it confirmed what people in the community had known for years. In September 2021, Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser announced his office had investigated the Aurora Police and Fire Departments for more than a year, and found “a pattern and practice of racially biased policing.”

The investigation was extensive: it involved data analysis, which showed that nearly half of the individuals whom Aurora Police used force against were Black, even though Black residents make up about 15% of the population in Aurora. Black people were also twice as likely to be arrested than white people.

The attorney general’s team also sat in on meetings of the police board that reviews incidents of force and found Aurora didn’t adequately scrutinize its own behavior. Investigators also rode along with officers on patrol; reviewed thousands of pages of police reports; and interviewed officers and residents, among other things. The investigation also found consistent illegal use of ketamine, a powerful sedative, by paramedics.

When Weiser announced the findings, he said, “What Aurora needs, we’ve heard loud and clear, is a law enforcement system that is worthy of their trust.”

In the weeks after, the city signed onto an agreement with the attorney general, called a consent decree. The city and state spelled out a series of specific reforms to hiring and training practices; policies around use of force; and more. The agreement, or decree, is scheduled to last five years.

It’s the first time in state history that a city has entered into such an agreement with the state, and it was made possible by a law passed in the wake of Elijah McClain’s death.

This week, criminal trials for the three officers who forcibly stopped and subdued McClain are underway. That may result in personal, criminal responsibility for his death. The reforms required in Aurora are another form of responsibility: they are an attempt, for the first time in state history, to establish that individual incidents can be the product of a system that has not valued the lives of all people in the community. It’s an attempt to hold an entire system accountable, and ultimately, to improve public safety.

Almost two years since the decree was established, everyone involved agrees that progress has been slow, perhaps out of necessity, and has been made mostly behind closed doors. It is testing the patience and trust of a community in which some people say they can’t wait.

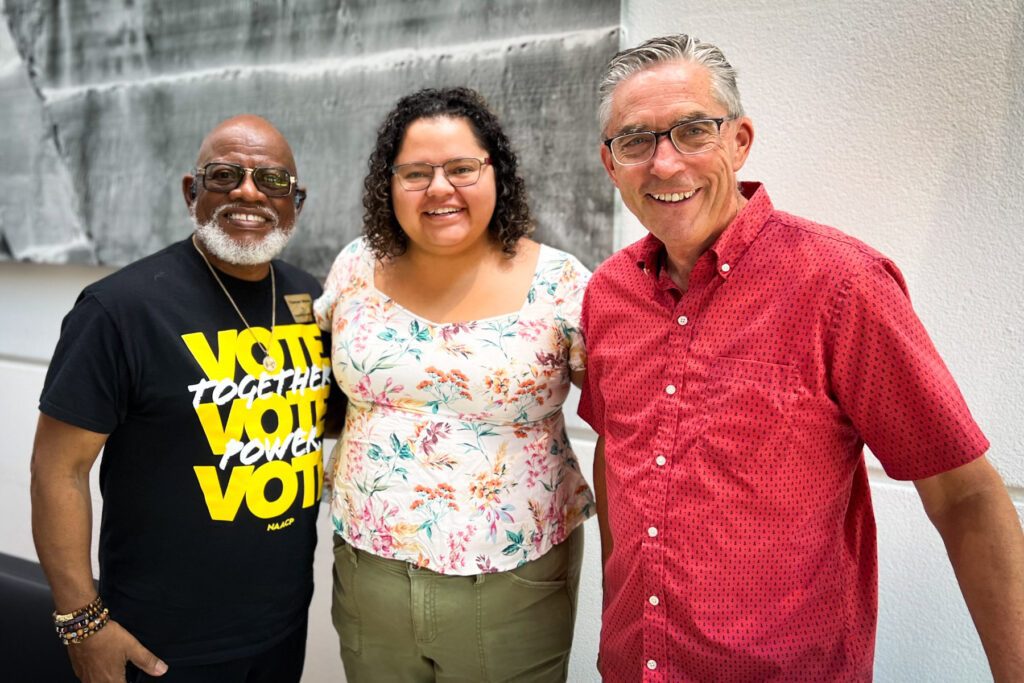

“Patience is a luxury that our communities just cannot afford,” said Gianina Horton, an Aurora resident who works in the field of civilian oversight of law enforcement as co-director of the Denver Justice Project. She also serves on a community advisory council to the consent decree monitor. The council is intended to communicate the status of the reforms to the Aurora community, and transmit questions and comments up to the independent group that’s overseeing the five-year process.

Horton added, “There are so many officers that are working with due diligence to make these reforms happen, and I acknowledge that and validate it. And at the same time, there needs to be accountability in real time.”

Thomas Mayes, a pastor at Living Water Christian Center Church in Aurora, is also on the community council.

“Just think of it: if your son was dead, and (someone says), ‘Be patient. Give us five years to fix what caused his death.’ That’s a struggle for the community.”

For many years, community members had been talking about the same patterns of racist policing that the attorney general formally identified two years ago

Hashim Coates, a political strategist and community activist in Aurora, said Weiser’s team did not reveal anything that he didn’t already know. He believes the attorney general and the Aurora police already knew, as well. “What he did though, was actually put some teeth into what we knew,” said Coates.

Both Coates and Mayes had heard warnings about police when they were young, growing up in Denver. Both of their families warned them, as Black boys, not to go to Aurora for fear of police violence.

Coates and Horton are among those who said they do not yet see substantial changes to policing in Aurora. Mayes added, “I’m not happy with how slow the pace is going.”

Some community members are frustrated by incidents that predate the consent decree, and situations where extreme force has been used during the period of oversight. For example, in August 2020, officers handcuffed a Black family, including children as young as five years old, because they mistook the family’s car for a stolen vehicle. Officers did not face charges.

In June 2023, an officer shot and killed a 14-year-old boy, Jor’Dell Richardson, who was suspected of participating in a robbery with a weapon that turned out to be a pellet gun. The department said his killing was a tragedy, but that officers were justified in shooting him.

Mayes said he and those around him are just trying to live, and while he understands there is crime in Aurora and that officers are human and capable of making mistakes, he wants things to change to where Black people do not have to be unjustly cautious in order to survive.

“That’s why I say we have to restructure the police department, and not just in Aurora. Law enforcement nationwide needs to have that happen,” Mayes said.

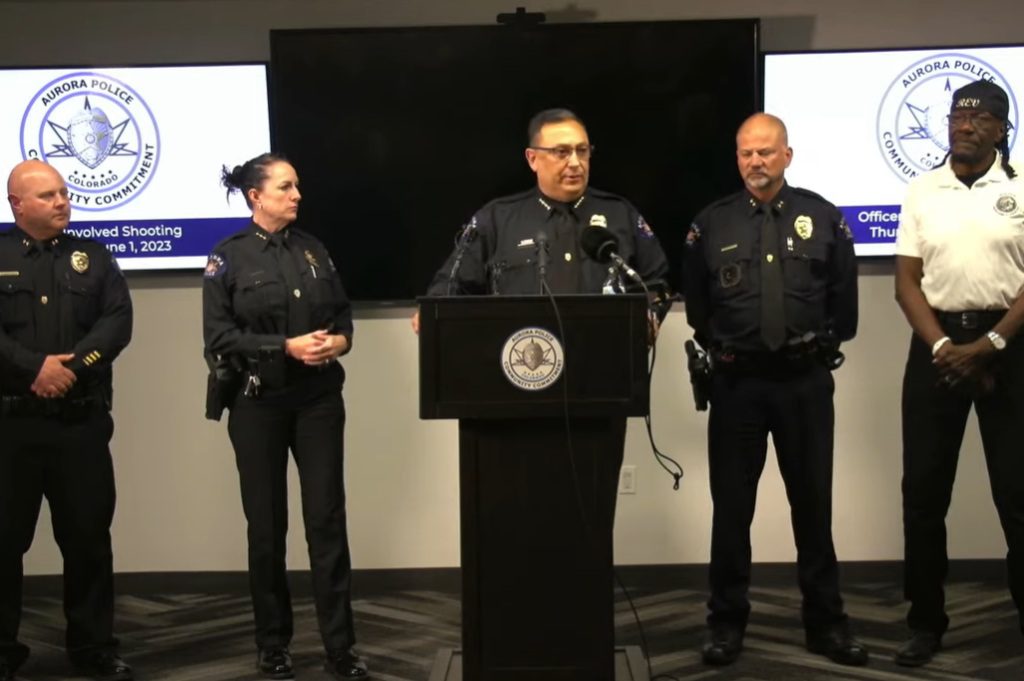

The man leading the company, IntegrAssure, that is independently overseeing the reforms in Aurora is Jeff Schlanger. He said he’s not surprised the community doesn’t see changes yet, because much of the work that’s been done is behind the scenes – it’s mostly around crafting new policies.

Then, over the next three years, Schlanger’s team will guide Aurora to implement the new policies, “to make sure that all of those changes are being felt on the streets of Aurora, and that officers are abiding by those reforms,” Schlanger said.

IntegrAssure is paid by the city to be the overseer, but Schlanger said the city can’t dismiss his company even if it doesn’t like his assessments.

Aurora is making progress, according to the independent overseer

Schlanger’s team has noted progress in some areas: For example, after his team criticized the lack of accountability in scrutinizing their own uses of force, Schlanger said Aurora Police is making progress on more critically reviewing officers’ conduct.

Additionally, Aurora paramedics no longer use ketamine as a sedative.

Horton credits Interim Police Chief Art Acevedo with stepping up his transparency. She said she saw Acevedo make a concerted effort to be more forthcoming about what happened.

Interim City Manager Jason Batchelor said he’s most encouraged by changes that have been made to recruiting and hiring practices. He said Aurora had 33 recruits start at the training academy in September, which is a larger number than the city has seen in a few years.

“They’re coming through a very rigorous process that is making sure that we’re getting the right candidates in there,” Batchelor said. “And so we’re seeing people that are stepping up, that are committed to policing in Aurora, they’re committed to policing well, and they understand the consent decree. They want to be part of those reforms that are in the consent decree.”

Acevedo, too, said many officers already on the force want the same things their critics do: clear expectations and consistent enforcement of the rules.

“Policing is like society, it’s a work in progress, right? With change, you always have to continue to grow and be a learning organization. So I’m excited to be here because there’s a thirst by our officers to strengthen, win over, build upon the trust that we enjoy from the public now, they want to strengthen it. They want to do well,” Acevedo said.

The consent decree monitor has identified other areas in need of much more work

Schlanger points to two ongoing deficiencies: Aurora Police have not been able to establish a thorough enough training on bias prevention; and they are not able to collect thorough data to see if there are patterns in police conduct, such as their uses of force.

A new bias training program was tested earlier this year, and Schlanger points out that members of the community were invited to the test, and their feedback was included in the decision that a better training program needed to be developed.

Regarding data collection, Schlanger said that could include demographics of people stopped by police, demographics of people who police use force on, statistics about the time of day stops happen and the locations, and more.

“We need all that data to make certain that the department is not in any way acting in a biased manner, and that it is using force appropriately, and we are working to make sure that those systems are updated appropriately so that the appropriate analysis can be done,” he said.

But Mayes, the community council member, is skeptical.

“At the end of the day, why aren’t you keeping statistics on that? Because that is the problem, that people of color are being treated differently than others. Those are the types of statistics we need, and that we have to be able to share with the community,” he said.

Additionally, Schlanger and his team are undertaking a thorough review of body camera footage, which they say has been inadequate. This is a challenge not just in Aurora: Schlanger, who has overseen reforms at several police departments across the country, said that for the most part, despite mandates to wear and keep body cameras running, departments do not effectively review all of that footage often enough.

“There isn’t enough review of what is being done on the streets by police officers so as to correct little mistakes before they become big mistakes,” he said.

In addition to the progress on specific reforms, some community members want Aurora to go further in their commitment to better and more equitable public safety

On top of changing the policing practices, Horton wants to see Aurora put more money toward alternatives.

“How do we invest in mental health professionals and substance abuse and addiction professionals? Because we can’t expect law enforcement to know all of that,” she said. She wants to see Aurora expand its Mobile Response Team, which currently only works on certain hours and certain days.

She and fellow council members including Omar Montgomery, who leads the local NAACP, also want Aurora to invest permanently in an independent monitor’s office – a place to review policies, specific incidents of violence, and to do proactive outreach to the community.

The result, Horton said, would be that “when we need to push on the departments for change and for policies and practices, we’re not just secondary opinions, but we’re providing primary input, and we can have a stronger community presence behind us.”

The city decided last year that funding a permanent office of the independent monitor could be redundant with the work Schlanger’s team is contracted to do. Batchelor said the city plans to establish the independent monitor office after the five-year consent decree ends, but Pastor Reid Hettich of Mosaic Church of Aurora is among the community council members who are not satisfied with that conclusion. They believe the positions would serve different functions, and the permanent independent monitor’s office is urgently needed.

Still, Hettich is choosing to be optimistic about the change that the consent decree can bring about. He’s been involved in several civilian efforts to reform public safety in the city.

“I do have some hope that this process is different than some of the processes of the past, in that there’s real teeth with the attorney general behind it, and the attorney general watching it,” he said.

The community advisory council plans to hold its next meeting for members of the public on October 24. IntegrAssure plans to release its next progress report on the consent decree later this month.

This piece was republished from CPR.