Brutality and Deaths Inside East Baton Rouge Jail Spark Uphill Battle for Reform

By Piper French

On August 18, 2034

Harsh treatment of protesters led to more activism against the notorious Louisiana jail, which has long been overseen by a sheriff facing reelection this year.

Kaddarrius Marquise Cage was experiencing a severe mental health crisis when he entered the East Baton Rouge jail in late May. The 28 year old had stabbed his stepfather in the midst of an acute psychotic episode, but his mother, Kim, says that neither she nor her husband, who was badly wounded in the attack, thought that jail was the right place for Kaddarrius, who suffered from paranoid schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. They were told there was simply no other option.

The deputy who arrested Kaddarrius “assured me that he was being put on suicide watch,” Kim told Bolts. “It was all a lie.”

Kaddarrius’s stay at the jail, formally known as the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison (EBRPP), disrupted his normal medication schedule, which Kim suspects destabilized him even further. On the morning of May 31, guards found him hanging in his cell. “I called the jailhouse every day for 12 days begging and pleading with them saying please let me—can you have my son call me, can I speak to my son, my son’s not in his right mind,” Kim said. “If I was able to get his medicine to him, my son would be alive today.”

Between 2012 and 2016, the EBRPP had a death rate more than twice the national average, according to a Reuters analysis. Since 2012, there have been 59 fatalities in custody. Jail staff have long faced allegations of neglect and deadly lapses in medical treatment, and in 2016, the brutal treatment of people arrested and jailed for protesting the Baton Rouge police killing of Alton Sterling sparked a movement for jail reform.

The man who has overseen the jail for 15-plus years, East Baton Rouge Parish Sheriff Sid Gautreaux, has often blamed the deaths on the building, which activists, politicians, and sheriff’s department officials alike agree is antiquated and dangerous. Gautreaux, a Republican, has for years sought to replace the current jail with a new, even larger facility, but voters have shot down requests for funding to build a new one. The sheriff, who is also the parish’s chief tax collector, has faced allegations of profiting off his office, raking in significant campaign contributions from contractors during elections where he has run unopposed or lacked a significant challenger. This includes thousands of dollars in donations from a law firm that has represented Gautreaux and his co-defendants against plaintiffs whose loved ones have died in his jail.

Despite his track record, Gautreaux seems likely to secure reelection once again this year. East Baton Rouge has reliably voted for Democratic governors and presidents over the last decade, and Mark Milligan, a Democrat who challenged the sheriff in 2019, is running again, as well as two other candidates. But none of the three challengers appear to be actively campaigning less than two months out from the October 14 election. Four years ago, Milligan received only 17 percent to Gautreaux’s 70 percent.

“Unfortunately, again, because the majority of our residents are not in tune to what’s going on at Parish Prison until it hits them personally…he continues to fly under the radar,” said Baton Rouge Metro Council member Chauna Banks, a Democrat who has previously called the jail a “money grab.”

Gautreaux didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.

Family members of people who died at the jail, advocates for reform, and academics who have studied deaths behind bars there blame the sheriff as well as the warden, Dennis Grimes, and negligence on the part of guards and medical staff for these deaths. But they also blame larger systemic failures that have turned jails into a backstop for people experiencing addiction, instability and mental health crises.

A paucity of mental health services across Louisiana, as well as the jail’s use of solitary confinement and other practices that can exacerbate mental health crises, only intensify the problems at the lockup, says Reverend Alexis Anderson, the co-founder of the EBRPP Reform Coalition, which has both established a support network for people who have lost loved ones inside the jail and fought to transmit their message to a broader community that remains largely unaware of its issues.

Anderson said a new jail, which the sheriff continues to advocate for, won’t fix the problems illustrated by a steady stream of tragedies there. In her view, rampant criminalization, from schools to traffic stops to unhoused people, has contributed to a ballooning jail population. She also pointed to the defunding and privatization of state services that ramped up under Louisiana’s former Republican Governor Bobby Jindal, which led to the closure of the charity hospital where incarcerated people in mental health crisis were once sent and paved the way for a private, for-profit company with a long history of scandals to take control of healthcare in the jail. Meanwhile, high bonds and a lack of pretrial reform have also left people who are legally innocent to languish in jail with little treatment for years on end.

“Mass incarceration is our number one industry,” Anderson told Bolts. “Conversations about the building take away from the real work that we as a community need to do…so we aren’t continuing to use a jail as a de facto mental health facility, as a de facto addiction detox center, as a de facto cooling center for people who are struggling with domestic violence.”

Rather than building a new jail, the EBRPP Reform Coalition seeks to install an independent monitor to oversee healthcare and conduct investigations of deaths and abuses in custody, so that people aren’t effectively forced to file a lawsuit to try to figure out what happened in their relative’s last moments. Advocates also wish to put an end to the use of solitary confinement inside the jail, and they want fundamental changes in how the country treats residents struggling with addiction, homelessness, and mental illness, with the ultimate goal of incarcerating fewer people.

In addition to these changes, the coalition is demanding accountability for the suffering the jail has already caused—something a new building alone can never address. “A facility didn’t kill my uncle,” said Sherilyn Sabo, the niece of Paul Cleveland, who died in the jail in 2014. “Three deputies tased him while he was having a heart attack.”

Not long after Baton Rouge police killed Alton Sterling in 2016, one of Linda Franks’ clients called her to make a salon appointment. Over the phone, she told Franks that she had been arrested during the demonstrations roiling the state capital. “She was very, very, very upset,” Franks recalled. The client told Franks that she and other protestors booked into the jail were pepper sprayed, denied access to basic hygiene products, and left in a freezing cold cell without blankets. It seemed like the guards were retaliating against them for going out to protest Sterling’s death.

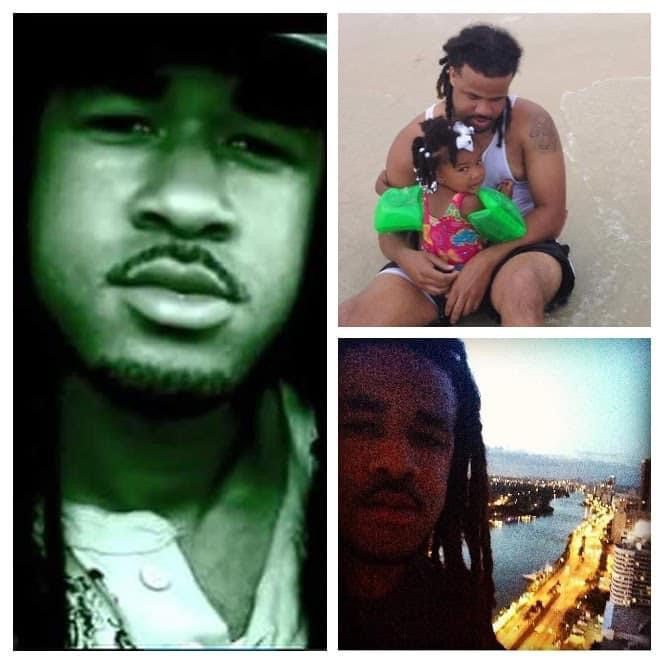

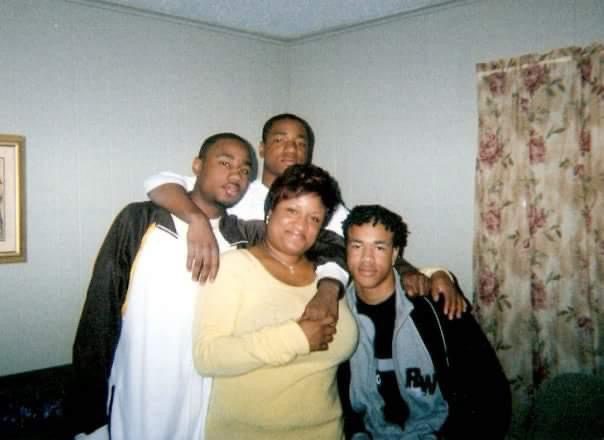

The year before the protests, Franks’ son Lamar Alexander Johnson had disappeared inside that same jail after an officer pulled him over for having tinted windows and discovered that he had an old warrant for a bad check in another parish. “Lamar was like, ‘Mom, you know, everything’s fine. I know I had a traffic ticket,’” she told Bolts. “And four days later my son was hanging in a cell.”

Franks says that Johnson had never before experienced any issues with his mental health in his 27 years. “He was always the peacekeeper,” she said. “He was just an amazing loving father and very attentive to his children.” He lingered on life support for a week, enough time for Franks and her husband to make sure his vital organs went to save a 9-year-old boy who needed them.

Johnson’s passing, in early June 2015, marked the beginning of a furious quest for Franks to understand what happened to her son and prevent others from suffering similar tragedies. She founded an organization called the Fair Fight Initiative. Along with Reverend Anderson, Franks also established the EBRPP Reform Coalition, and started talking to her friends and customers about her work — including the client who called the salon to relay her detention horror story after the Alton Sterling protests.

Around the same time, Andrea Armstrong, a law professor at Loyola University New Orleans, began receiving a flurry of calls from students who were serving as legal observers during the protests. Their stories led to a 2017 report titled “Punished Protestors: Conditions in East Baton Rouge Parish Prison,” that detailed the abuses visited upon demonstrators during their stays in EBRPP.

“I’ve been writing about jail and prison conditions for my entire career, but I had never necessarily focussed on a particular facility,” Armstrong told Bolts. She decided to dig deeper, especially after talking to Franks. Armstrong recalled her questions: “Was her son the only one to die this way? You know, ‘Are they telling me the truth about what happened to my son?’”

Gautreaux, has downplayed deaths in his custody by citing the prevalence of addiction and comorbidities amongst people in his care. More than any other part of the criminal legal system, jails tend to admit people in a state of crisis—which is precisely why speedy medical and psychiatric care, addiction treatment, and regular observation are so important in that setting. But Armstrong also seeks to trouble the assumption that death is simply an inevitability, pointing to nationwide statistics that suggest that the vast majority of jails lack a fatality in any given calendar year. “Death is and should be a rare occurrence behind bars,” she told Bolts.

Diving into EBRPP’s statistics was no easy feat: there was next to no information publicly available. “When we started looking at it, nobody had a list. Nobody was tracking—not even the jail, in a publicly accessible way, at least—who was dying, and why and how,” Armgstrong told Bolts. When Armstrong got records for EBRPP from between 2012 and 2016, she found that 22 of the 25 men who had passed away during that time were legally innocent: They had died awaiting trial. “Their deaths were preventable,” she wrote in a follow-up report. Inspired by her work in EBRPP, Armgstrong would eventually go on to map deaths behind bars throughout the state.

Despite its name, the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison is a jail, not a prison. The vast majority of its residents are pre-trial, and there’s very little in the way of programming for people incarcerated there, said Amelia Herrera, an organizer with the Baton Rouge chapter of the group Voice of the Experienced who was incarcerated there for a number of months in 2015. But at the same time, people often live there for months or years on end. “Entering jail now is like throwing the dice—you don’t know what’s going to happen,” she said. “Every call is like a 911 call.”

Anderson has been court watching at the local district courthouse for nearly five years. Almost everyone she sees is eligible for bond, suggesting they’re not considered a threat to public safety, but the amounts are set so high that very few people have a hope of posting. Sabo’s uncle’s bail, for instance, was set at $300,000. “How many of the people that you’re holding, you’re only holding there because of poverty?” Anderson asked. “I watch one on one who’s coming in that jail, and I can tell you disproportionately that so many of those people are not medically stable when they get there…We have lots and lots of people [who] go in there because we’ve criminalized mental health.”

Until 2013, when Republican Governor Bobby Jindal began decimating the state’s charity hospital system (he ultimately shuttered or privatized 9 of 10 facilities), people incarcerated at EBRPP who needed medical care—about 35-40 patients a month—would be taken to the Earl K. Long Medical Center. When the city took over the provision of healthcare services, moving all medical care inside jail walls, things quickly went downhill. A 2016 evaluation by an outside consultant group would deem healthcare at EBRPP “episodic and inconsistent.” At the time, nurses who worked there told the Baton Rouge Metro Council that they frequently lacked basic supplies such as neosporin, and that the jail’s EKG machines could not effectively determine whether someone was in the midst of a heart attack or not. “I can personally attest to them not coming out to give insulin, not checking blood pressures,” said Herrera. The year after she was there, eight people died.

However, a for-profit carceral healthcare company called CorrectHealth was already in touch with city officials before the 2015 evaluation was even completed. Problems with medical care persisted even after 2017, when the city passed responsibility for healthcare provision off to the company, which has been dogged by lawsuits and is run by a doctor who oversees prison executions in his spare time.

EBRPP Reform Coalition has been active in the fight to send the company packing. They won a partial victory when the metro council underwent a more transparent contract bidding process and ended up choosing a different company, Turn Key Health Clinics, to take over healthcare provision. But Anderson stressed that without an independent healthcare monitor, any progress that might have been achieved by CorrectHealth’s ouster is incomplete. “We are getting the same bad results because we are doing the exact same things,” she said. Meanwhile, Anderson has counted at least nine fatalities since the new company took over in early 2022—a bleak form of déjà vu. “The deaths keep coming,” said Herrera.

A mental health facility called the Bridge Center for Hope opened in early 2021, an event city officials heralded as transformative for the provision of mental health care in the parish. The 24/7 taxpayer-funded crisis center––the only one in the state—includes a crisis observation unit, a short-term psychiatric unit, and a detox unit, according to their website. But Anderson stressed that most people with mental health issues who cross paths with the sheriff’s department may require longer-term care. In court, she told Bolts, “many of the people who come through with behavioral health issues are not short-term care people. They’re already in our existing mental health system. And so what they need to be connected to is their existing system.”

Jail staff also continue to put people with mental health issues in solitary confinement. Johnson, Franks’ son, was in solitary for a time before his death, and Herrera spent nearly a month there when she was in jail in 2015 after struggling with her mental health in the wake of her mother and husbands’ deaths. “The jail isn’t equipped to handle anyone with a mental illness,” she said. “Instead of receiving help that I really needed, being incarcerated and thrown into a cell….” Ultimately, Herrera said she wasn’t permitted to see a psychiatrist until four months had passed.

During the pandemic, in an effort to keep the isolation that incarceration engenders at bay, the EBRPP Reform Coalition staged a monthly “caravan of justice” outside the jail. “We wanted a way for people being detained as well as people that worked there, to let them know that someone is watching,” Franks said. “I just felt like someone needed to hear a horn blow. I just, I thought, you know, if Lamar heard a horn blow that morning….I don’t know what that would have accomplished, but god put that on my heart to do.”

Despite the body count and rotating cast of healthcare providers at his jail, Gautreaux has largely stayed out of the limelight, all while raising hundreds of thousands of dollars in campaign funds, serving a term as president of the Louisiana Sheriff’s Association He has easily won every election he’s faced, even receiving endorsements from prominent local Democrats despite running as a Republican.

Gautreaux has a powerful fundraiser and ally in Alton Ashy, a prominent lobbyist for Louisiana’s booming gambling industry who has also served as his campaign chairman and treasurer. Ahead of a December 2022 parish vote on a millage tax to fund the sheriff’s department, Ashy set up a PAC to advocate for the measure, raking in donations from casinos, bingo distributors, and a for-profit correctional services company.

In a 2021 report, the government accountability group Common Cause singled out Gautreaux for the breadth and depth of donations he has received over his career that represented potential or outright conflicts of interest, including money from CorrectHealth. The report also pointed to a law firm, Erlingson Banks PLLC, that donated to the sheriff and handles the sheriff’s office’s public records requests. Court records show that the firm has also represented the sheriff and other jail officials in multiple lawsuits over jail conditions and in-custody deaths. Mary Erlingson, a partner at the firm who has served as Gautreaux’s general counsel, is also listed as treasurer on the millage tax PAC, which was created to advocate for funding for the sheriff’s office.

Meanwhile, according to the Common Cause report, Gautreaux has accepted over $150,000 in contributions from construction companies since his initial campaign in 2008. One construction company owner donated $50,000 in one fell swoop to the millage tax PAC in 2022.

Given all this, advocates are suspicious that the sheriff’s desire for a new jail is less about seeking to improve conditions than the potential for other collateral benefits. Gautreaux initially argued for a 3,500-bed facility, twice what the jail currently possesses, leading some to suspect that he intends to take advantage of a common practice in Louisiana where the state pays sheriffs a per diem to house people in the state prison system. (Under Louisiana’s only 287(g) agreement, the sheriff’s department also collaborates closely with ICE, including holding people in custody for 48 hours after a judge has said they’re free to go so that the agency has time to come pick them up).

“All the research indicated we needed a smaller jail, and we needed to operate in a more therapeutic way,” said Banks, referring to a report commissioned by the MacArthur Foundation, which recommends reducing the jail population. “I know for a fact that would not be a model that the current warden who is running the jail or Sheriff Gautreaux can actually execute.”

The gulf between the power Gautreaux has over parish residents’ lives and the amount of power that they in turn believe they have over his continued employment there frustrates Anderson enormously. “One of the things that I’m constantly in the business of doing is reminding people that you have to have skin in the game.” It’s difficult to convince people, though, when Gautreaux so resoundingly trounced his two opponents in 2019, and no one is yet running a robust campaign to defeat him with the primary just two months away. “If we don’t see a change, these may be some of the most historically low turnouts we’ve ever seen,” Anderson said. Still, “groups like ours will keep reminding people: there is a cost to not paying attention,” she said.

For Linda Franks, a big part of the fight has been striving to make sure that the broader community understands the horrors of the jail as viscerally she and others who have lost loved ones inside do. She talks to her coworkers and clients at her salon about her work; the EBRPP Reform Coalition tries to do a press conference every time there’s a fresh death. But she recognizes that it’s an uphill battle.

Just last week, on August 10, a local news site reported that a 25-year-old man named Kiyle Maxwell killed himself in police custody while waiting to be transferred to EBR Parish Prison.

“He didn’t even make it to the jail,” Anderson said.

This piece was republished from the Bolts Magazine.