Community land trusts turn LA tenants into owners

By Zoie Matthew

April 19, 2023

Jose Lopez loves just about everything about the Baldwin Hills apartment building where he’s lived for two decades: the big, grassy courtyard in the middle where he can sit outside and listen to the birds, the neighborhood cat that regularly visits his elderly father, and most of all, the intrinsic sense of community.

“It’s very inviting, it’s warm. It’s like it’s giving me a hug,” says Lopez. “I can see all my neighbors, and if they walk out: ‘Buenos dias, ¿cómo estás? How are you doing?’ It’s very communal.”

Lopez doesn’t want to live anywhere else. That’s why when his building and three others nearby went on the market – potentially threatening more than 100 tenants’ abilities to keep living there – he and his neighbors jumped into action. They are now pushing to become co-owners of the buildings themselves — by way of a community land trust.

It’s an increasingly popular housing model in LA that aims to preserve affordability by letting tenants cooperatively own and make decisions about the places where they live. And a new surge in public funding means it’s likely to become a lot more common here.

What is a community land trust?

Essentially, community land trusts (CLTs) are nonprofits that buy up property so they can use it for the benefit of a community – think parks, community gardens, civic spaces — or, as is increasingly the case in Los Angeles, affordable housing.

When a community land trust buys a residential building like Lopez’s, it owns the land under that building and promises to keep it permanently affordable. Tenants own the units they live in by way of a 99-year contract that hands over responsibility for the building to residents.

Usually, those tenants pay rent into a common fund, and form a co-op that makes decisions about remodels, community rules, and repairs. In some ways, it’s similar to a condo conversion. But the goal here isn’t profit. It’s community building.

“The most important word in the community land trust is ‘community,’” says Damien Goodmon, who founded the Liberty Community Land Trust in South LA. “When people see themselves tied to … the broader collective, that’s when the real power manifests itself.”

A push for community control

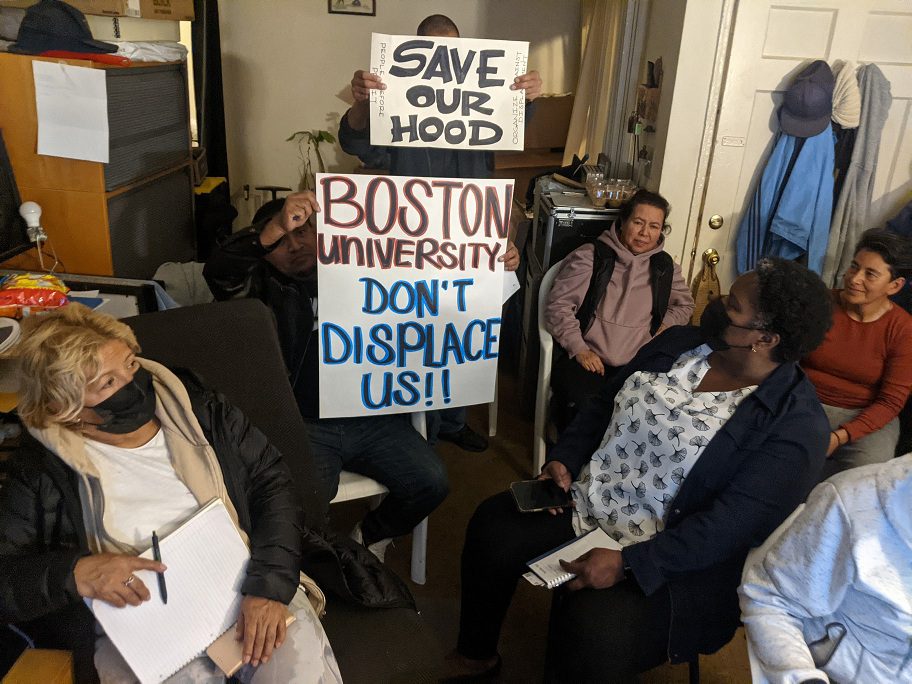

For Lopez and his neighbors, the path to community ownership began in winter 2022, after a wealthy philanthropist named Fredrick S. Pardee passed away and left four Baldwin Hills apartment buildings he owned — including the one Lopez lives in — to his alma mater, Boston University.

The university quickly put the buildings up for sale, and it wasn’t long before real estate speculators in fancy cars began pulling up in front of Lopez’s home.

“They were walking through, and the salesperson was saying, ‘Hey, are you seriously interested?’” says Lopez. “And I said, ‘Okay, this is going to flip real quick, and I’ve got to do something about it.’”

He worried that if the university sold the buildings, he and 130 other tenants in the mostly Black and Brown community would be displaced from their rent-controlled units. Most pay hundreds of dollars below market rate — and if rent went up, they would not be able to stay in the neighborhood, where a one-bedroom now costs around $2,000 a month.

Irma Galvez, who has lived next door to Lopez for a decade and makes her living vending corn, ice cream, and other treats nearby, is sure she’d be priced out. “Everybody knows me because I’m selling in the neighborhood,” says Galvez. “So for me, it’s important. This is my house, it’s my job. It’s everything.”

So Lopez, Galvez, and their neighbors began organizing. They worked with the Los Angeles Tenants Union to learn their rights, met with residents of the three other buildings Boston University was now selling, and searched for ways to stay. That’s when they reached out to Goodmon at the Liberty Community Land Trust.

“We were on the phone with [Boston University] within two and a half hours, telling them that we wanted to purchase the buildings,” Goodmon recalls. “[We] have been working with the tenants for the purpose of preserving their affordability into perpetuity, and getting the tenants in a position to own their units collectively.”

Now, just four months later, Goodmon is finalizing a contract to buy those four properties. Once the ink dries, Liberty Community Land Trust plans to rehab them — and then, eventually, transfer ownership to the tenants.

Learning how to take care of a building is going to be a big change, says Lopez. But he’s confident it’ll be worth it.

“Rather than having to follow the landlord’s rules, we’re going to be able to say, ‘What do we want? What are our rules? What does our paradise look like?’” says Lopez. “‘Do we want a fire pit in the middle of the lawn right here, an avocado tree right here? Do we want to put carrots in and grapes? What do we want?’ And that’s agency, right? That’s autonomy, that’s beautiful. Not a lot of people ask poor people: What do they want?”

A boost in public funds

The community land trust model is not a new way of preserving affordable housing in the United States. Its roots date back to the civil rights movement when it was used to help protect Black sharecroppers from displacement. But until recently it was rarely used in Los Angeles — in part because real estate here is so expensive.

That began to change in 2020, when an LA County pilot program forked out $14 million to help five local community land trusts acquire and rehab eight residential properties across LA. The focus was on saving smaller multi-family apartment buildings, which make up a lot of LA’s affordable housing stock, but are rapidly being scooped up by speculators.

“More traditional affordable housing developers just won’t want to take on the smaller multi-family properties, because it’s too much on their bottom line to be able to manage and do the rehab,” says Natalie Donlin-Zappella, who worked on a report about the county pilot program for the nonprofit Liberty Hill Foundation.

Community land trusts can circumvent some of these issues by passing along management responsibilities to tenants. And they can be cost-efficient too. According to the Liberty Hill report, the acquisitions funded by the pilot cost the county about half as much per unit as new affordable construction projects.

“It’s the best deal out there,” says Goodmon. “If you want to keep people from being unhoused, you’ve got to keep them in the affordable housing they’re in right now.”

In total, the county pilot kept 110 LA tenants in stabilized affordable housing. It also helped LA community land trusts prepare for a new surge in public money that’s coming from the voter-approved tax Measure ULA, also known as the “mansion tax.”

The city measure, which is expected to bring in nearly $700 million over the next fiscal year, will dedicate almost a quarter of its funds towards alternative modes of affordable housing, including community land trusts.

Another 10% of the money raised will help those organizations do more tenant outreach and education. And that’s important because while buying a building is easy — if you have the funds — learning to live collectively takes a lot longer.

The path to cooperative living

It can sometimes take years before a community land trust fully transfers a building to its residents. In fact, of the eight buildings acquired under the county pilot program since 2020, none have yet reached the final stage of resident ownership. That’s in part because living cooperatively is a big shift from the typical tenant-landlord dynamic, says Kacey Ventura, director of organizing and advocacy at the Beverly-Vermont Community Land Trust.

“Often, [in] the new buildings that we acquire, these are tenants who are learning these models for the first time, and they’re models that are not necessarily taught,” he says. “So it’s always a slow process.”

In buildings that are not already organized, tenants might need time to get to know each other. And when buildings do have a strong community, residents still will need to work together to answer some big questions — like, how much do people need to pay to have a share in the co-op? And what will the community decision-making process be?

Smaller, day-to-day issues such as who is responsible for repairs also need to be addressed. For that, learning how to navigate conflict is key, says Ventura.

“You’re going to come into conflict, and that can hold things up,” he says. “But if you know how to deal with each others’ conflict, it makes discussing things like, ‘What should we do if someone clogs the pipes and busts all the pipes?’ It makes that conversation a lot easier.”

In a bright yellow fourplex on Kenmore Avenue in Koreatown, a group of women called the Señoras for Housing has been having these conversations for nearly two years.

The Beverly-Vermont Community Land Trust acquired their building in 2021, after they fought off a landlord’s attempts to push them out. Since then, they’ve been outlining the rules for their new co-op and saving up for the future improvements they want to make. Rent is no longer rent, says future co-owner Ixchel Hernandez — now it’s a monthly “caring charge.”

“That caring charge is going directly into our building — into any emergencies. If we want to build something for our community, if we want to do renovations to bring pride into our building,” says Hernandez.

Co-owner Alejandra Valles faced harassment and an eviction attempt from the previous landlord, making stability and ownership especially meaningful to her. She says one of their most important decisions was to make Señoras for Housing a limited equity co-op. That means if members leave, they won’t get back more than they paid — preserving affordability for future residents.

“We’ll never make a profit, really,” says Valles. “But it will never leave this community. This building and this land will always be here and it will never be allowed to be bought out by these rich people that just want to displace us.”

The ultimate goal, Valles says, is to pass the home on to future generations – like 17-year-old Diana Martinez, who has lived here all her life.

“It gives me hope for the future,” says Martinez. “It gives me a sense of security, knowing that my mother, I won’t have to worry about her well-being and whether or not she can pay rent.”

The Señoras hope to have full ownership transferred to them before the end of the year — and to be a model for many other future co-ops that will crop up in Los Angeles as Measure ULA money begins to flow.

As for Jose Lopez in the Baldwin Hills building, he says he and his neighbors are excited to get their co-op started soon, too — and to remain in their homes indefinitely.

“I don’t want to live anywhere else but this place. I want to die here. I’m happy,” he says. “This is where I want to be.”

This piece was republished from the KCRW.