CPS school-based budget formula targets schools with high needs

Even with shifting priorities, the school district says it has successfully maintained the funding it provides to schools overall.

By Nader Issa and Sarah Karp

On May 29, 2024

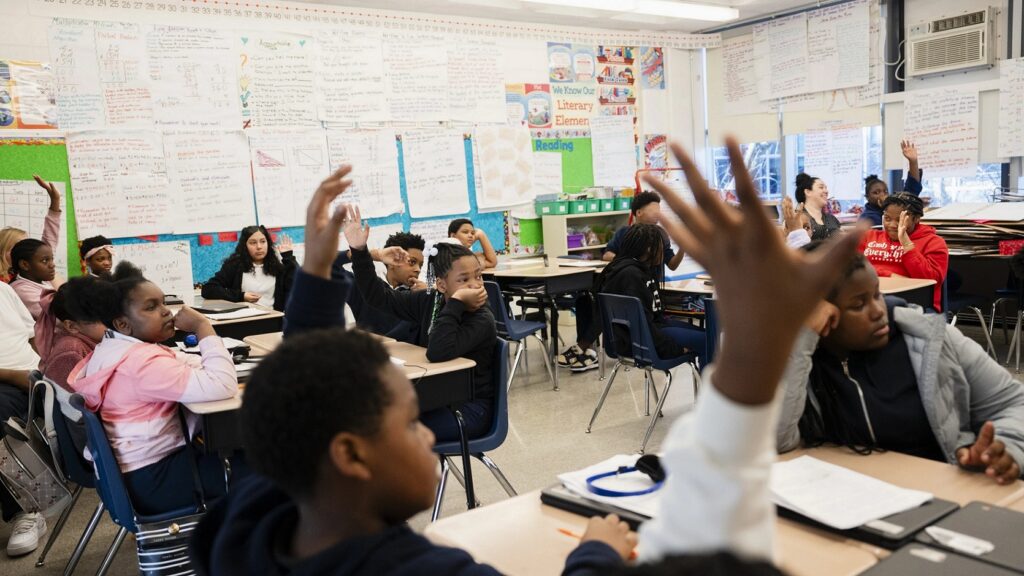

Pat Nabong/Sun-Times file

A new Chicago Public Schools budgeting formula designed to redistribute resources based on students’ needs is shaking up a school system that has long budgeted based largely on student enrollment, budget documents released Tuesday show.

Some schools that serve mostly middle-class families are seeing cuts in staff, even though they are serving roughly the same number of students. But many high-poverty schools that continue to lose enrollment are also losing teaching and other staff positions.

The glaring exception is super small schools that serve almost all low-income students that were given a baseline of staff plus extra positions, like all schools under the new budgeting formula. Douglass High School in Austin has only 35 students this year, but is getting 10 additional staff positions. Holmes Elementary School in Englewood on the South Side has 117 students, but will have more than 30 positions next fall or one for every roughly four students.

Even as the school district is shifting priorities, it appears to have successfully maintained the funding it provides to schools overall. That’s despite a nearly $400 million deficit that’s expected to grow with a new Chicago Teachers Union contract in the coming months. Leaders said they will instead look to close the gap through cuts in central office spending.

The school-level budgets CPS published Tuesday look significantly different from prior years because of a new funding model that grants schools a standard number of positions for administrators, teachers and some support staff, then additional support for schools with higher needs. CPS previously gave each school an amount of money that principals used to build a staff based in large part on student enrollment.

For that reason, CPS CEO Pedro Martinez said it’s difficult to compare changes at schools this year with previous years. But he vowed that both the total funding and positions in schools would not decrease — even if some schools gain and others lose.

“This is a new base model, so we don’t have direct apples-to-apples comparisons,” Martinez told reporters Tuesday. “Where I am seeing the pattern of concerns — and it’s a handful of schools, it’s not a large number — is in schools who have had historically rich elective programming. Multiple electives [classes], four or five, six, plus, in addition, very low poverty.”

A Chicago Sun-Times and WBEZ analysis shows the district is budgeting for 36,074 school-based staff positions for the school year that begins in August. That’s about 150 more than the 35,926 positions at the start of this school year, data show, but about 500 fewer positions than the district has today. But that might not mean fewer adults in schools, because there are around 1,700 unfilled jobs today, meaning only 34,841 adults are actually working in schools right now.

One of the biggest areas of growth is among special education classroom assistants. CPS is planning to employ 6,179 next fall, about 200 more than at the start of this school year. But the district appears to be budgeting for fewer special education teachers. Martinez has said CPS is seeing more students enrolled in special education.

In addition to the baseline of positions, CPS gave principals so-called “discretionary funds” to spend on anything they still need, which could include more teachers or staff, or programs run by community groups. Schools are funding 1,136 staff positions through that money, plus another $94 million in non-staff support.

About 110 schools are expected to see a 5 percent or more decrease in budgeted staff this fall compared with last fall, according to the WBEZ/Sun-Times analysis. And although CPS leaders say they are shifting money to the neediest schools, some of those hit the hardest are high schools that continue to see declines in enrollment and mostly serve students from low-income families.

Two South Side high schools, Harlan and Phillips, and one West Side high school, Crane Medical, are getting 20 percent fewer positions, the analysis shows.

Many selective enrollment and magnet schools complained they are losing staff, but the picture is complicated. Several are using virtually all of their discretionary money to buy staff positions to offset losses.

For the first time, CPS is acknowledging that some schools have an advantage if they can raise significant private money. In its budget presentation, CPS shared data showing that 28 schools paid for54 staff using student fees, outside grants and fundraising this year. A small number of schools in CPS, often without many students from low-income families, have historically raised private money to support school programs.

CPS officials stressed that none of the district’s 500-plus schools are fully funded because the school system itself is underfunded. Mayor Brandon Johnson, Board of Education President Jianan Shi and Martinez — alongside the CTU — lobbied Springfield for extra education funding this spring, but there’s no additional help in the budget bill passed by the Illinois Senate over the weekend. The Illinois House is expected to vote on the deal this week.

This piece was republished from WBEZ Chicago.