Deaths in Pa. jails are undercounted. Our investigation found dozens of hidden cases

By Joshua Vaughn and Brittany Hailer

On November 9, 2023

Jeff Lagrotteria and Tina Talotta waited 30 minutes before doctors would allow them to enter the hospital room where their cousin Anthony Talotta was barely alive, breathing on a ventilator.

“Because they had to prepare him for us to see him,” Lagrotteria said, referring to his shocking appearance.

Talotta had been living at a group home for men with intellectual and psychiatric disabilities where, after an altercation, a pot of boiling water fell on him and on a worker. Police were called and Talotta was taken to a hospital Sept. 10, 2022, and then to the Allegheny County Jail. His foot had second-degree burns, torn ligaments and fractures.

Eleven days later, the family hadn’t been told anything about what landed Talotta in the hospital, that it was his second hospitalization during his brief incarceration or that he had been treated for an infection on his foot.

When the cousins walked into the ICU on Sept. 21 and saw Talotta, they were stunned at his condition — black and blue blooming up his leg. The doctors didn’t explain how Talotta’s leg had become so infected, but said they were “tending to it.”

The cousins also learned their 57-year-old relative was suffering from septic shock, which had triggered a heart attack.

“We didn’t realize he was basically dead,” Lagrotteria said. Talotta didn’t survive the day.

He was one of 17 people to die while in custody of the jail from March 2020 to September 2022.

Talotta’s story encompasses much of what can go wrong inside Pennsylvania jails. He was released from custody while dying in the hospital and his death was not reported to the Department of Justice or the Department of Corrections by the Allegheny County Jail, as required.

This lack of reporting by Pennsylvania jails is widespread, resulting in severe undercounting of deaths in the commonwealth. PennLive and the Pittsburgh Institute for Nonprofit Journalism undertook a six-month investigation to create the first comprehensive database of such deaths in Pennsylvania.

The investigation identified at least 65 deaths in custody across the state last year, only about 40 of which were reported as required.

Some county governments circumvent the requirement to report deaths by releasing jail residents before they die. Some county coroners refuse to provide the names of people who died while in custody of local jails, despite state law that makes that information public.

Most people held in county jails have not been convicted of crimes and are awaiting trial.

Details provided in autopsy records also vary by county, and some death records obtained in the course of the investigation lacked vital information. They did not indicate, for example, that an individual was housed or died in custody, including in Talotta’s case. His report also neglected to say he was found in the jail’s mental health unit, then rushed to a hospital.

This investigation turned up dozens of deaths that weren’t properly reported across Pa., but because of breakdowns in the system, there could be even more. There is nothing in place to ensure these deaths are counted, or even investigated.

The problem extends beyond Pennsylvania. Deaths in county jails across the country are subject to the same haphazard reporting and lack of accountability.

“We have a moral and legal obligation to document and investigate every single death in custody in order to acknowledge the dignity of the person who died, to develop strategies and policies to minimize future deaths in custody, and to hold responsible parties — whether they be individuals or institutions — accountable when they have behaved in a negligent manner,” said Jay Aronson, co-author of the book “Death in Custody: How America Ignores the Truth and What We Can Do about It.”

“Without accurate data, we can’t do any of these things.”

‘Getting to the truth’

The Talotta family filed a federal lawsuit in October alleging doctors and medical staff at the Allegheny County Jail provided substandard care.

They discovered after Talotta’s death that Wilson Bernales, the responding physician at the jail, had his medical license revoked or suspended in eight states. He also had injected Anthony with Benadryl, a treatment for an allergic reaction, instead of dealing with his life-threatening infection, according to the lawsuit.

According to Alec Wright, an attorney representing Talotta’s family, ambulance workers contacted Bernales, asking for Talotta’s medical history: How did the leg get this bad? What contributed to the cardiac arrest?

In records obtained for this story, EMS reported that jail “medical staff did not provide ambulance workers with any medical records, medical history, medication list or other supporting documentation.” Jail medical staff told EMS that “something went wrong with the printer” at the jail, according to EMS records.

Ambulance workers questioned Bernales in order to understand the reason for Talotta’s medical emergency,

“When asked for clarification what the patient’s symptoms at that time of the medical emergency were, the doctor responded that the patient presented as not responding verbally and was immobile,” EMS reported in the emergency log.

Despite further attempts, “the doctor was unable to provide a clear picture of the patient’s status at the time of the medical emergency.”

The Talotta family found themselves in an alternate reality. Once they entered the hospital room, they had to make end-of-life decisions for their cousin, a man whose IQ hovered somewhere above 60. He had been entrusted to their care after his mother, Lena Talotta, died, leaving a $1 million trust that her son could live on without her guiding hand and vigilance.

“I was shocked that happened to him,” said Tina Talotta. “When Aunt Lena was [dying] she was afraid that something was going to happen to Anthony. I said, ‘I’ll take care of Anthony.’ But my guilt is if I could have taken him in, would this still have happened?”

The Pittsburgh Institute of Nonprofit Journalism first learned of Talotta’s death shortly after it occurred when anonymous sources working in the jail said Talotta had been released from custody before he died.

The Allegheny County Medical Examiner determined Talotta died naturally of a heart attack and, outside of jail and hospital medical records, the story of Talotta’s infection remained hidden until his family’s lawyers requested and obtained additional documents.

Getting to the truth in jail deaths is costly, and many families don’t have the resources to hire attorneys to learn what happened to their loved ones.

In those cases, that means the public doesn’t get to find out the truth, either.

Wright estimates a typical jail death case costs between $15,000 and $30,000 to obtain records, retain forensic medical experts, understand family history, and piece together a narrative of how someone like Anthony Talotta died in custody.

For attorneys like Wright, who practice on a contingency fee, it also costs between $35,000 and $50,000 in attorney hours to determine what really happened. So, the total cost to fully investigate a jail death in order to file a lawsuit can be upwards of $80,000.

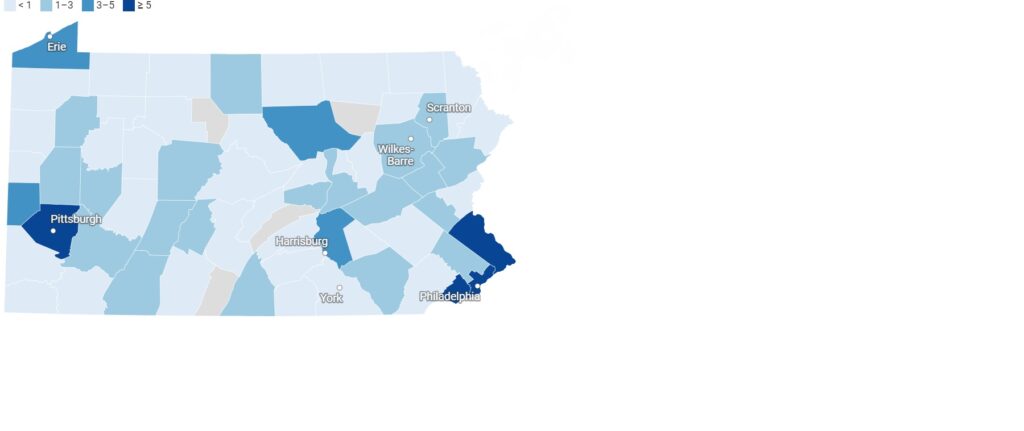

In-custody deaths in Pa. jails in 2022

The first-ever database

Talotta’s is one of at least 26 jail deaths that weren’t properly reported last year, but were revealed as part of the investigation by PennLive and PINJ to create the first statewide database of jail deaths. The database will continue to be updated as we learn of new deaths.

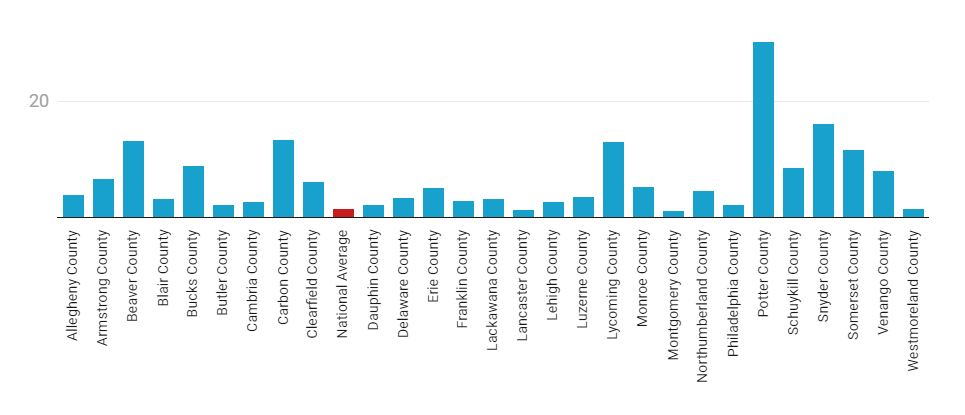

The database showed the highest number of deaths occurred, not surprisingly, in the largest counties. But it also delivered some surprises as far as counties with higher death rates, which are calculated against the jail’s daily population.

Overall, Philadelphia County logged the most in-custody deaths last year with 10. The county is the largest in the state, and features several jails with an average daily population of more than 4,400 people.

Allegheny County, the state’s second-largest county, also ranked second in deaths along with Bucks County, with six people dying in each county. Allegheny County’s jail population averages around 1,500 daily, while Bucks’ is around 675.

Delaware County, the state’s fifth largest, reported five deaths with an average daily jail population of about 1,450 people.

Nine more counties with populations ranging from 150 to nearly 1,000 had at least two people die in jail last year, and 15 counties reported at least one death.

In all, at least 28 counties had someone die while in custody. That means 39 counties reported no deaths.

The county with the highest death rate had one death in 2022: Potter County.

Thirty-one-year-old Paul Sparkman Jr. died by suicide fewer than five days after entering the facility that August. That death stands out because the county is among the least populated in the state and the jail’s daily population is low, about 33 people each day.

The database showed Carbon County had two deaths and roughly 150 people incarcerated each day. Both people in the Carbon County jail died by suicide.

Allegheny and Dauphin counties both ranked above the statewide and national average jail death rates, according to the PennLive and PINJ investigation.

Cumberland, Perry, Lebanon and York counties reported no deaths last year, and this investigation found only one death in Lancaster County.

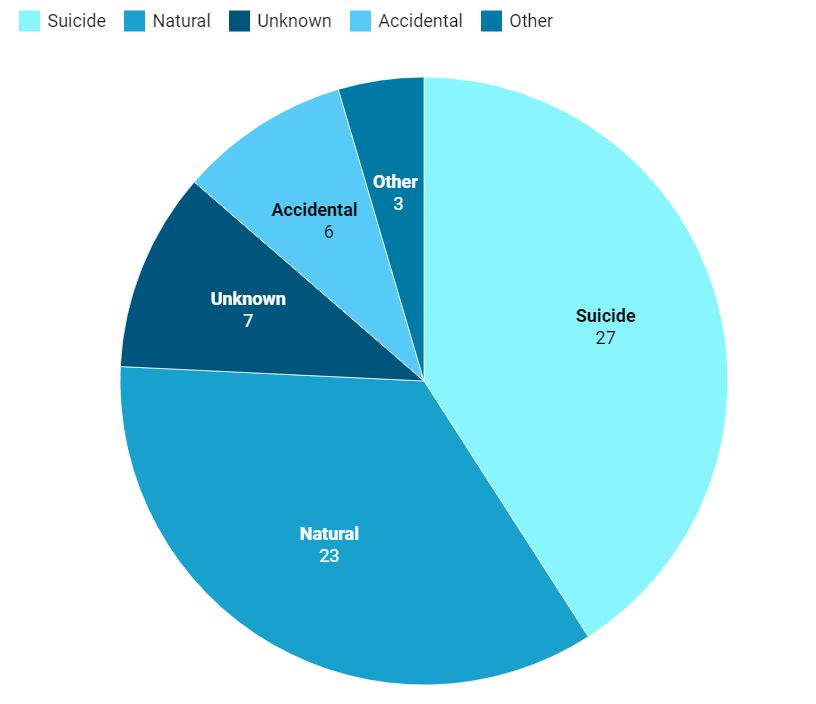

Manner of death in Pa. jails in 2022

Based on official manner of death

Suicide was the most common manner of death in all counties except Allegheny, accounting for roughly 40% of all deaths in jails.

Suicides deserve additional investigation and accountability, according to advocates, because those cases can reveal deficiencies in jail policies and practices.

In one case a man died by suicide by drowning in his cell.

In that case, 38-year-old Trent Mason died in February after he broke the fire-suppression sprinkler in his cell, according to a report filed by Philadelphia officials and submitted to the federal Bureau of Justice Administration.

By the time corrections officers noticed the sprinkler was broken, Mason’s cell and his entire pod of other cells were flooded. Officers said they attempted to perform CPR on Mason, but he was pronounced dead in the jail by medics, according to the county.

Eight deaths were classified as accidental, most of which were overdoses, but this also includes at least one person who choked to death.

Two men also died by homicide in jails last year.

Darwin Pasos-Santos, 33, died in Lackawanna County Prison in June 2022 after he was assaulted by another incarcerated person. Fifty-four-year-old Elliot Funkhouser died in April in Delaware County jail after he was strangled by another incarcerated person, according to prosecutors.

Only one death among the 65 across the state was listed as undetermined, which means the coroner could not decide on one of the four manners of death — natural, homicide, suicide or accidental. That individual was Jamal Crummel, a 45-year-old man who died in Dauphin County Prison in January after developing hypothermia twice in his cell.

Crummel died on Jan. 31, 2022, one week after he returned to the jail after being hospitalized for hypothermia. His official cause of death is listed as cardiac fibrosis — a thickening of the heart caused by a heart injury — with hypothermia being a significant contributing factor.

About 30% of deaths in jails last year were classified as natural with causes ranging from COVID-19 to complications of chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD.)

While these deaths are ruled as natural, it doesn’t mean the jails bear no responsibility for the loss of life or that the person’s death wasn’t preventable.

‘Natural’ deaths

Medical providers at UPMC recorded “septicemia” as the cause of death for Anthony Talotta, which means blood poisoning by bacteria.

But the Allegheny County Medical Examiner ruled he died naturally of hypertensive and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

Talotta’s autopsy report cites the second-degree burns on his leg, but does not include any details or history of treatment for the infection.

“When we die, any of us, it is because our heart stops,” Wright said. “And if you die from an infection, if you go into sepsis, and then cardiac arrest — ultimately, you will die from your heart.”

Wright said the Allegheny County Medical Examiner should amend Talotta’s cause and manner of death based on the medical reports he has seen in the case.

“There is no doubt in my mind that if the Allegheny County Medical Examiner’s Office looked at Anthony’s autopsy again, an amendment will be required.” Wright said. “And they absolutely should do that. And they absolutely should look at the other causes of death for the individuals that have been brought to them from the Allegheny County Jail.”

Of the 65 known jail deaths in Pennsylvania in 2022, 14 were ruled ”natural” by coroners or medical examiners, but that determination might not tell the whole story of how someone died.

Andrea Armstrong knows this too well.

She founded IncarcerationTransparency.org, a database that provides facility-level deaths and analysis for Louisiana. She was named a 2023 MacArthur Fellow, regarded as one of the nation’s most prestigious awards for intellectual achievement. The award, commonly known as the “genius grant,” carries an $800,000 stipend.

She has reviewed hundreds of deaths in custody and said the system can play a role in a natural death, but government documentation limits our understanding of the care or events that happened prior to someone’s heart stopping. Natural deaths should be due to “internal factors, not external forces,” she said.

“These controlled environments, that control what you eat, what air you breathe, what clothes you wear, whether you have access to medical care, what quality of medical care you have access to and frequency, all of those things affect a person’s health and could affect, in fact, the progression of a disease,” she said. ” So it’s not clear to me that ‘natural’ is really portraying what the cause of death is. I think it is much more complex when we look at deaths in these highly controlled environments.”

Terence Keel has also reviewed hundreds of autopsies of law enforcement deaths in his national research for the BioCritical Studies Lab at the University of California, Los Angeles. In his work, deaths ruled natural have also become a point of concern.

Natural deaths can include cases where an incarcerated person wasn’t given their medication and they died because of a chronic condition. That kind of system “really just launders all the kinds of violence or medical neglect that’s happening in the jail,” Keel said.

“George Floyd’s death would have been a natural death had it not been for the fact of Darnella Frazie recording the video and showing us otherwise. Because the coroner said he had a pre-existing heart condition and fentanyl intoxication,” Keel said.

‘We’ve never had anyone die here’

Simply getting autopsy reports, which are public records under Pa. law, is another challenge.

Autopsies were provided in Allegheny County this year after Allegheny v. Hailer, a state court decision that forced the medical examiner to provide the autopsy records of Daniel Pastorek, a man who died in the Allegheny County Jail in November 2020.

It took three years of pushing by a journalist to get the reports, which then revealed an autopsy was not conducted.

Instead, the medical examiner did an “external review” of the body. Pastorek died naturally of heart disease, according to the medical examiner.

Across the commonwealth, journalists, researchers and advocates are working to access records of men and women who die in custody, but running into the same problems: difficulty getting the documents, and questions about their completeness and costs. The cost of autopsies are set by state law and run nearly $1,000 to obtain the full autopsy report, coroner investigation and toxicology.

Christina VandePol, the former Chester County coroner, decided not to run for reelection in 2021, citing frustrations with the county after pushbacks to her attempts to “modernize” the office. When she began her term, she was given a tour of the nearby jail. She asked the warden what the protocol was for a death in custody.

“And what the warden said to me was, ‘Well, we’ve never had anyone die here.’ This warden had been at the prison for 40 years, so I knew that couldn’t have been true,” VandePol said.

For two years, no deaths were reported. That warden retired. Then COVID-19 hit and VandePol started getting calls from the jail.

“And we all looked at each other because we’d never had a death at the prison. And we didn’t have a protocol,” VandePol said.

After researching deaths in custody and conducting her own investigation into jail deaths, VandePol said she reached the conclusion that a full autopsy should be conducted for any death in custody, even one believed to be natural.

“It’s my opinion that the medicolegal death investigation of anyone in the custody of the state should be as complete as possible. With few exceptions, a forensic pathologist should do a full autopsy with both external and internal examination plus toxicology,” VandePol said. “Prison deaths happen behind closed doors, so the coroner or medical examiner has a duty to be transparent as well as accurate.”

How long coroners and medical examiners keep their records is another issue.

Natural deaths records, according to VandePol, are destroyed by Chester County after seven years, which means autopsies of any “natural deaths” in custody can no longer be reviewed or accessed.

Hidden deaths

Talotta is not alone in having a “natural” but possibly preventable death while behind bars.

On July 5, 2022, Cara Salsgiver was arrested in Venango County and taken to the county jail. The 49-year-old woman survived fewer than two weeks in the jail because of lack of medical care, according to a lawsuit filed in federal court by Salsgiver’s family.

Several days before she died, Salsgiver begged for help, according to the lawsuit. Her legs had become so swollen as a result of a kidney infection that she was unable to walk. Other incarcerated people tried to get the attention of staff to help her, but, according to the lawsuit, medical staff ignored them.

She “suffered immense physical injuries” leading up to her death on July 18, 2022, according to the lawsuit. Her cause of death was ruled natural, the result of severe kidney infection.

Salsgiver’s family is represented by Brian Zeiger, a lawyer from Philadelphia. Zeiger is also representing the family of Joshua Patterson, a man who died in Bucks County Prison in August 2022 of a fentanyl overdose. His case represents another way deaths can be hidden away.

Patterson’s death does not appear on any official death registry, and officials in Bucks County did not publicize that he died or that they had arrested a man who they say caused his death.

Patterson was found unresponsive in his cell on July 27, 2022 and rushed to a hospital.

According to police, Allen Rhoades, 31, had distributed fentanyl throughout the jail leading up to Patterson’s death. Rhoades did not have special access to get in and out of the jail. He was incarcerated just like Patterson.

Police wrote in the affidavit that Rhoades snuck numerous bags of fentanyl into the jail in part because the police who arrested him and the corrections officers at the jail failed to properly search him.

Video from inside the jail shows Rhoades took drugs out of his pants while in the holding cell and slipped them into a brown bag of food that officers had given him, according to police. On at least two occasions, Rhoades pulled the drugs out and snorted them while in a holding cell, police said.

Once he was in general population, Rhoades is accused of selling the drugs to other incarcerated people, including Patterson.

Patterson survived for a little more than two days after he was found and rushed to the hospital. That was enough time for county officials to have his bail modified and release him from custody.

Rhoades is charged with felony drug delivery resulting in death and faces up to 40 years in prison.

Since Patterson was not in custody at the moment he was pronounced dead, Bucks County did not report his death to state or federal authorities.

That is a common tactic used by counties in Pennsylvania and across the nation to skirt reporting requirements, making it extremely difficult to know if any count of deaths in jails is accurate.

“We say ‘at least,’” Armstrong said about how she discusses deaths in custody in Louisiana. “That’s what we know and there are likely more.”

Paul Spisak’s death following his incarceration at the Allegheny County Jail also went unreported to the federal and state governments.

He suffered blunt force trauma when he fell in his cell and was discovered “in front of his toilet,” according to Allegheny County Police Inspector Michael Peairs. His death was ruled an accident by the county medical examiner.

Spisak, 77, a former Catholic priest who was named in the state’s 2018 grand jury report on clergy sexual abuse, died at Allegheny General Hospital following his collapse in his cell on Jan. 22, 2022. Spisak was in a “semi-conscious state” and was “not coherent,” according to Peairs.

There are no cameras in the cells due to privacy reasons, Peairs said, but their investigation concluded that Spisak “hit his head somewhere in his cell.” Spisak was in a single cell and did not have a cellmate, according to Peairs.

The court released Spisak from “custody” six days after his collapse due to his deteriorating medical condition at the hospital. The Jail Oversight Board was not notified of Spisak’s release or death.

Spisak’s death became public through media reports, and the Pittsburgh Diocese was notified of his death.

Like Spisak, Talotta was released from custody when it became apparent that end-of-life decisions needed to be made at the hospital.

Medical releases for incarcerated persons who become injured or ill while in custody are common across jails in Pennsylvania and the U.S.

PINJ and PennLive filed right-to-know requests with all 67 counties across Pennsylvania, requesting jail medical releases. The records received were incomplete, redacted or denied, making it nearly impossible to know the extent of the problem.

Public record denials and redactions of hospital release records further obscure who is dying and whether their incarceration played a role in their death.

Death-in-custody checkbox

Armstrong, who tracks deaths of Louisiana jail residents, has called on the government to provide more transparency and accountability to strengthen reporting of deaths in custody.

Roger Mitchell, co-author of “Death in Custody” and former medical examiner of Washington, D.C., who previously worked in several jurisdictions across the country, said he noticed that deaths in custody were often not investigated in a standardized and objective manner.

“I started advocating for a death-in-custody checkbox,” Mitchell said. “We have the best vital records system in the world and we use it to capture data about the kinds of deaths we want to prevent. We should want to prevent deaths directly attributable to interactions with the criminal legal system. Using the death certificate to capture information about deaths in custody seems like an obvious and rational policy choice.”

If a death-in-custody checkbox existed, regional and federal fatality review commissions could look at trends of deaths in jails and prisons and could suggest new public health policies, Mitchell said.

A bill introduced by Sen. Amanda Cappelletti, D-Montgomery and Delaware counties, would do that in Pennsylvania.

Cappelletti introduced the bill earlier this year following reporting by PennLive and PINJ about the lack of reporting of deaths in jails. The bill, which is modeled after Texas state law, would make it a misdemeanor for counties to not report deaths in jails and expand the definition of what qualifies as “in-custody” to include someone who dies several days after being released from custody while in the hospital.

“It’s not clear to me that this should be my job,” said Armstrong, who tracks deaths in Louisiana. “I think this is actually a quintessential government function. It should be tracking, and analyzing and evaluating its own performance and providing a safe and secure environment for holding people in custody. That is its job.”

Armstrong said she also supports a policy proposal by Carnegie Mellon Professor Jay Aronson and Dr. Roger Mitchell, chair of pathology at Howard University, that would create a universal checkbox for death certificates to indicate whether a death was a result of incarceration.

Armstrong said regardless of what the policy solution is, it is incumbent on the public to take a greater interest in what is going on behind bars to reduce the number of preventable deaths.

“All of this has been done in our name, and with our dollars and with our support,” she said. “So, that’s the part that I would say is most important. These are our institutions. What happens is done in our name.”

This piece was republished from Penn Live.