Deep dive: Segregation crippled Fort Worth’s aquatics. Here’s how the city could recover its pools

By Rachel Behrndt

O September 15, 2023

A historic photo of Sycamore Park Pool is overlaid with Sycamore park in its current state. The park’s pool has been filled with dirt since its closure in 2014.

Ask any Como resident older than 30 and they’ll probably tell you that the Como pool was more than just a pool — and Brandney McCormick was more than just a pool manager.

In the 20 years McCormick spent managing Como’s pool, hundreds of children (including his own) learned to swim, dozens of community members found employment as lifeguards, and the manager provided mentorship, fun and even food to generations of residents.

“The pool was so important,” McCormick said. Several times, parents entrusted him and his lifeguards to watch their children through the summer months. Eventually, he formed a swim team, traveling around the region to competitions which created a fun and safe space for neighborhood kids to spend their summer.

Today, instead of a summer oasis, the Como pool is a concrete slab covered with a new playground. When it closed in 2014, McCormick was still managing the pool; he was crushed by the news.

“It meant so much to the community,” McCormick said. “I was shocked that they put concrete down (over) something that had meant so much to the community.”

Fort Worth is not unique from other cities that experienced a public pool boom in the mid-1900s followed by a decline in the late 1900s. However, many cities have recently reinvested in aquatics as an increase in drowning deaths disproportionately impacted people of color. The example other cities have set by consistently investing in pools with equity in mind could chart a path for Fort Worth to reinvest and recover some or all of the pools it has lost.

An outline of a small pool is still visible at the Lake Como park. The pool was closed in 2014 after budget cuts prevented the city from opening it up annually.

In 2014, Fort Worth permanently closed five of its seven pools, including Como’s, all of which were located in primarily Black or Hispanic, low-income neighborhoods. The move was dictated by the city’s 2008 aquatics master plan, which found that each of the city’s now-closed pools was losing about $30,000 annually. Maintaining the pools each season cost the city hundreds of thousands of dollars annually.

Which five pools closed:

- Sylvania Park Pool

- Sycamore Park Pool

- Lake Como Park

- Kellis Park Pool

- Hillside Park Pool

“Use of the pools was lagging,” Joel McElhany, assistant director of the city’s parks and recreation department, said.

To date, the city has declined to build its own aquatics facilities and instead opted to seek partnerships with the YMCA and school districts, a decision McElhany attributes to a lack of excitement for new pools at public meetings.

The tide is changing though, he said, as the city is currently working to renovate Forest Park Pool and build a new pool and community center in the majority-Black and Hispanic Stop Six neighborhood.

The parks and recreation department is already primed for change. The city is in the process of developing both a new parks and recreation master plan and a new aquatics master plan. Both documents will guide Fort Worth’s effort to maintain, and possibly build, more aquatic facilities.

Fort Worth’s pool history mirrors other cities

The city has significantly fewer pools than its similarly-sized counterparts in Texas and around the country. Many cities with fewer residents have more public pools. But why? Scholars say the answer can be traced to segregation-era racism, which led to white residents leaving integrated public pools and flocking to their own de-facto whites-only pools in neighborhoods and private clubs.

How many pools are in other major cities

Dallas with a population of 1,343,565: 17 pools

Austin with a population of 979,263: 33 pools

El Paso with a population of 681,729: 14 pools

Arlington with a population of 398,860: 8 pools

Fort Worth with a population of 913,656: 2 pools

This manifestation of white flight led city governments around the country to devalue public pools, often allowing them to deteriorate before closing. After integration was mandated by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education, cities chose to close pools rather than allow them to be integrated. In Mississippi, half of the public pools open in 1961 were closed by 1972.

Hispanic residents also suffered under segregation, and many of them were also denied access to pools. One of the first successful desegregation lawsuits in the U.S. was filed in 1944 against San Bernardino, California, where Hispanic children were not given equal access to the city’s pools.

News clips documented the day Como’s pool was dedicated by the city of Fort Worth as a segregated pool in 1958, two years after Black residents and the NAACP petitioned the city’s parks and recreation department to integrate Fort Worth’s six municipal pools.

The city’s pools were not integrated until the 1970s.

Nearly a decade after Fort Worth’s pools were integrated, the city began to periodically close them, including in the 1980s, when budget cuts caused their closure.

The city plans to include the neighborhoods with private pools in its new aquatic master plan to ensure the city is building pools in communities that lack those options, McElhany said.

Fort Worth’s Polytechnic Heights neighborhood, which used to house Sycamore Park Pool, illustrates the impact of racial segregation on the health of communities, TCU historian Cecilia Sanchez Hill said. Initially a majority white neighborhood, the neighborhood has since transitioned to a majority Black neighborhood and then a majority Hispanic neighborhood, according to the most recent U.S. census.

“When that community becomes majority Black, you do see a disinvestment of city services,” Sanchez Hill said. “When you have a community that’s lost that access to that power structure, then you have less opportunities to bring money into it and bring city funds into your community.”

‘A plan with no money means nothing’

Fort Worth can look to Baltimore as an example of a city invested in pools. As a result of a 1955 court case in Baltimore, a ripple of white residents fled public pools for private ones.

Despite this history, today Baltimore maintains 23 public aquatics facilities. Many are more than 50 years old, and all are in the process of replacement or revitalization. This year, when residents complained about the forced closure of a public pool, the city was able to answer with a 10-year plan to replace every public pool with a brand new facility.

Baltimore is using state money and its capital improvements program, a fund set aside to build new public buildings and parks, to improve its parks and recreation infrastructure.

“A plan with no money means nothing,” said Reginald Moore, director of Baltimore Parks and Recreation.

Both Fort Worth and Dallas primarily use their bond programs, which voters approve every four years, to fund new pools and expand existing ones. Bonds are a form of debt that allows cities to spend large amounts of money to build new facilities like roads, parks and pools. Dallas takes a similar approach to Baltimore to maintain its 17 aquatic facilities and sets aside money in nearly every bond program for aquatics.

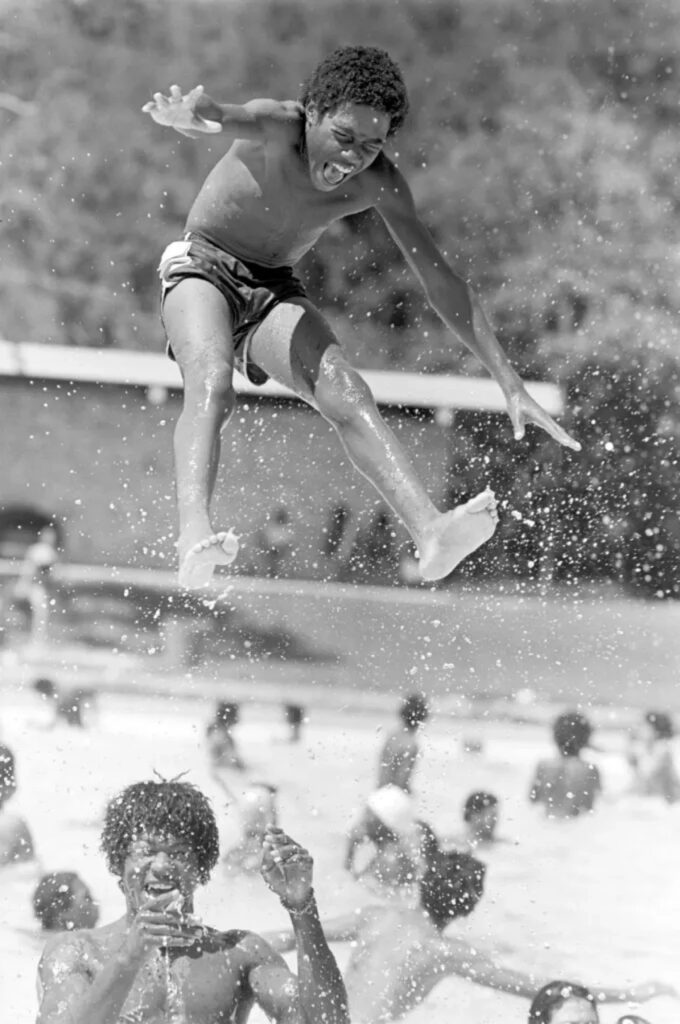

Out of the water and into the air goes Willie Brooks, thrown by Winfred King at Forest Park swimming pool in Fort Worth. Photographed in 1981 by Fort Worth Star-Telegram photographer Vince Heptig.

From 2004 to 2018, Fort Worth did not invest any money from its bond program into aquatics. However, in 2014 and 2018, the parks and recreation department started asking for funding to build two new pools. Each year, the request was denied because the council said residents at public input meetings didn’t mention pools as a high priority.

Finally, in 2022, pools made it into the bond program, McElhany said. Ever since, there’s been a shift in how vocal residents are about the need for new pools.

“There was enough support in 2022 and it really hasn’t gone away,” McElhany said. “It’s been an ongoing issue for residents.”

To encourage the city to keep investing in pools, residents need to keep speaking up, McElhany said. The city will begin a round of public engagement meetings for the parks and recreation master plan in October, immediately followed by public meetings for the aquatics master plan. Those meetings are expected to kick off in June 2024.

Moore’s advice? Lean on your master plans and use them as a form of accountability to continue investing in the department’s priorities. Create a plan and then put the money in place to get it done. When the loudest voices are the only ones the city is listening to, you start to leave residents out, he said.

At first McCormick dreaded working in the Como neighborhood. But when Viola Pitts, the unofficial mayor of Como, recruited him to re-open the neighborhood’s pool after it closed in the 1980s, he had a change of heart.

He had experience running swimming programs in his hometown of Birmingham, Alabama. In Como, McCormick found a community that went above and beyond to support his work at the pool. The neighborhood daycares and schools bused kids to the pool so their students could learn to swim under his watchful eye.

Since retiring from the pool and teaching at William Monnig Middle School, McCormick has time to walk every morning. He’s lost 100 pounds and his heart rate has slowed. Despite this, if the city reinvested in aquatics and reopened the pool, he would happily report for work to manage the pool again.

“If they built another pool and needed a manager, I would be the first one to run to Como,” McCormick said.

This piece was republished from KERA News.