DPS Report Outlines Unequal Barriers and Ceilings for Latino Students, Teachers

“There are some things that are hard to read,” DPS superintendent Alex Marrero said. “It’s something that’s a reality, and it shouldn’t be.”

By Chris Perez March 20, 2024

As the son of a Cuban refugee and an immigrant from the Dominican Republic, Denver Public Schools Superintendent Alex Marrero admits that the results of the DPS La Raza Report are a “painful” pill to swallow.

Reports of “white supremacy” throughout the school system and among DPS administration; a lack of resources for Latino teachers and students; low senses of pride and “identity” when it comes to being Latino; language barriers; suppression of cultural assets in the form of a “brown ceiling.” These are a few of the many problems plaguing DPS and Denver’s Latino community, according to the La Raza Report.

The report, a comprehensive analysis of fifteen years’ worth of data, was released on Tuesday, March 19, just one day before the 55th anniversary of the 1969 West High School Blowout, which saw Chicano and Chicana students walk out of class and protest over racism concerns and unequal educational opportunities.

The West High walkouts stemmed from a social studies teacher mispronouncing a Chicana student’s name, “Perez.” After the student corrected him, the teacher “deliberately began to pronounce her surname as Paris,” the report details. Now, La Raza researchers say institutional actions over the last half-decade have put “DPS and Latino families to a Crossroads,” with “serious movement” required to achieve ongoing and sustainable success for Latino students and their families.

“There are some things that are hard to read,” Marrero told reporters and members of the Latino community who gathered at DPS headquarters on Tuesday for the release of the La Raza findings. “It’s something that’s a reality, and it shouldn’t be.”

Dr. Alex Marrero, DPS supertintendent, was one of several people to speak Tuesday, March 19, about the La Raza Report findings.

Chris PerezResearchers with the Multicultural Leadership Center LLC partnered with DPS to unearth similar issues affecting Latino students and educators today by looking at data compiled from 2008 to 2022. The study was split into three parts: Historical Analysis, Quantitative Analysis and Qualitative Analysis.

Researchers took these three components and studied interaction through surveys, focus groups and data analysis to come up with a model for “ensuring academic, social and emotional success” for DPS students, the report says.

But first, DPS must address its shortcomings.

“It was painful to read the lived experience of some of our Latino students who, even amongst their Latino groups, lack a sense of belonging,” Marrero said.

Breaking Down the La Raza Report

According to the La Raza Report, there are many examples of “cultural dissonance” that Latinos experience in DPS, with parents, students, teachers and leaders expressing similar feelings.

“Many feel a cognitive dissonance in their interactions, when DPS’s stated beliefs do not align with its actions,” the report says. “This perception can cause not only perceived variance in how whites and Latinos are treated, but also conflicts between the two groups, including resentment against the ‘white supremacy’ Latinos state they experience. Students may feel unwelcome in class — whether because of other students or their teachers — as well as in the lunchroom, and even in sporting events, negatively impacting their academic and social achievements.”

There is also a “brown ceiling” for DPS teachers and staff, researchers note, with Latino faculty expressing that they’ve been limited in their “ability to best teach their students, as well as to advance professionally” due to their race or ethnicity.

“DPS Latino teachers and other staff were adamant about ‘white supremacy’ that they believe exists in Denver Public Schools administration,” the report adds.

Researchers cite an example provided by a Spanish-speaking teacher who said she interviewed for a kindergarten position and was passed over for a less-qualified white woman “who barely spoke Spanish.”

“[The Spanish-speaking teacher] noted that she had really strong academic data and was proud of the outcomes her students had when she would teach them to read and do math, they would leave kindergarten at beyond first grade level,” the report alleges. “And everybody knew that her data was stronger than everybody else’s that was interviewing for the position. The person that got the job, however…her data was horrible. She had horrible Behavioral Management, she couldn’t relate to Latina/o kids whatsoever, all of the kids she was going to teach were Spanish-speaking kids.”

According to the La Raza Report, the teacher left the elementary school and took a job at North High School, where she has since had positive experiences and is “pleased with the Latino administrators.”

Through its research, the Multicultural Leadership Center and its team addressed numerous questions related to the Latino experience in DPS, including: “What are the current barriers faced by Latino students, families, and staff within Denver Public Schools? What is the impact of these barriers on Latino students, families, and staff within Denver Public Schools? What are the current opportunities for Latino students, families, and staff within Denver Public Schools? What is the impact of the opportunities for Latino students, families, and staff within Denver Public Schools?”

Principal investigator and project director Dr. Steve DelCastillo tells Westword that several barriers stand out to him.

“First, you have to look at it from the family perspective,” he says, speaking after the Tuesday press conference.

“Sometimes parents were taking drugs, so, therefore, parents can’t have access to the school resources, and so on. So that really impacts the student. Then there’s the difference in terms of facilities, having access to things like materials, supplies, and stuff like that.”

According to DelCastillo, parents have noticed a discrepancy in school supplies between certain schools. Another major problem is the language barriers for Latino students, he says, adding that DPS needs “to be making sure they’re getting the same level of instruction as everyone else.”

Transportation, or lack thereof, is another key factor. “You have kids who sometimes have difficulty getting to school because they don’t have transportation,” he says.

DelCastillo thinks DPS would benefit by rethinking its current school boundaries, which could help neighborhood schools suffering from “school choice,” or when parents decide, “‘I live here but want to send my kid here outside the boundary, etc., etc.'”

One thing that bothers DelCastillo on a personal level, however, is the issue of identity.

“It’s something that’s very important. As people know, there are different terms that are being used now — Latino, Latina, Latinx, etc,” he explains. “It doesn’t make any difference, as long as there’s a sense of pride in that.”

DPS Latino Population and Recommendations

Alex Hegg, data scientist for the La Raza research team, notes that while Hispanic students still make up the majority of the DPS population, their lead has decreased over time.

“Their majority has shrunk gradually,” he tells Westword. “The next largest proportion, the white students, was growing pretty rapidly. There was a decline for all students during COVID for 2020, but by the end of the data set in 2022, the white student population — the raw number — had bounced back, but the Hispanic students hadn’t. The total student population has been increasing, but the proportion of Hispanic students has been decreasing relative to the number of white students.”

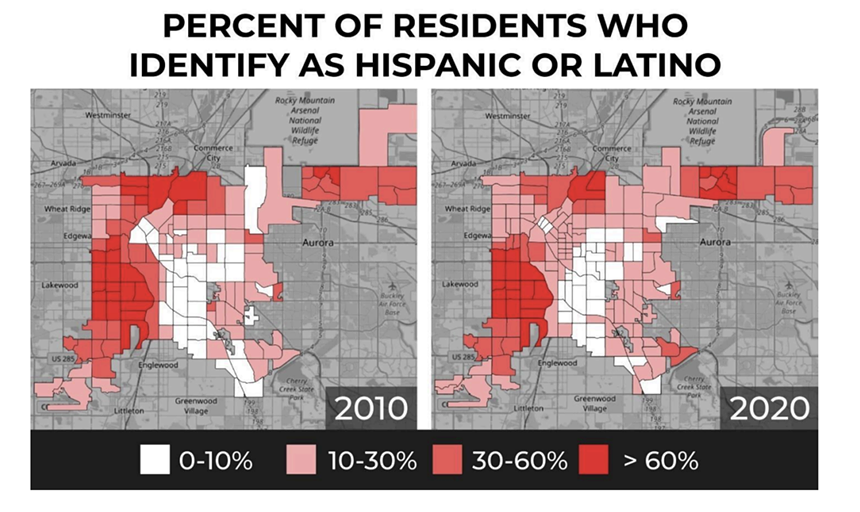

The La Raza data model didn’t look at causes, but Hegg believes population and identity shifts throughout Denver between 2008 and 2022 may have played a role.

“If we take it holistically with the other quantitative and qualitative analysis we ran for the report, you’ll see that we saw the shifts in populations across the DPS, where in 2008 through 2022 we saw concentrations of Hispanic students move to the northeast, into the southwest and out of the center and northwest — and conversely, concentrations of white students filling in those spots in the northwest and the center,” he points out. “So we can see there has been intra movement across the district.”

DPS/Multicultural Leadership Center

The data analyst notes that researchers did not have access to information for nearby school districts for the study, nor did they look into the recent influx of migrants from Venezuela and other countries that have been coming into Denver since late 2022.

“It’s possible that they could have been leaving the district area due to effects such as gentrification,” Hegg adds.

The La Raza Report comes with 35 recommendations for DPS and the city; researchers believe these will have an immediate impact on improving the Latino school experience. If they aren’t implemented, Hegg says, things could keep getting worse, leading to more and more Hispanic residents moving or getting their education somewhere else.

“There would possibly be a continuation of current trends where the proportion of Hispanic students, as a proportion of the student body, would continue to decrease,” Hegg says. “But that’s if nothing else in the world changes.”

Some of the recommendations put forth include the creation of a Latino Student Initiative to improve test scores, a “Grow Your Own” teacher development program aimed at bringing in Latino educators and more bilingual teachers, and the creation of a new school transportation system through a partnership with the Regional Transportation District (RTD).

One thing that gives DelCastillo and his research team hope for the future is the positive feedback they received from Latino parents, specifically Spanish-speaking ones, about the eagerness from DPS to change the culture, similar to the way it did following the 2016 “Bailey Report.” Led by Dr. Sharon Bailey, the comprehensive study on the experiences of Black students and educators led to a DPS Black Excellence Resolution and systemic changes throughout the district.

“They were saying that they felt comfortable with the district and felt accepted by the district,” DelCastillo recalls. “That, for me, was key. Because we go through all the numbers, and that’s easy to do; it’s when you hear those stories, to me, that’s what is powerful.”

Another nice thing to see, Hegg says, is the fact that the La Raza Report uncovered “no statistical differences” between district-run schools and charter schools. He notes how public charter schools have been gaining popularity, locally and nationally, for the past couple of decades due to their cost-effectiveness and ability to keep up with district school test scores.

“From a policymaker perspective, whether or not you support charter schools, in my opinion, should depend on what the data says,” Hegg tells Westword. “If they are outperforming district schools, that’s not to say that the district will shut down, but perhaps administration should look at where they are succeeding, and vice versa. If the district-run schools are outperforming, they should be talking to each other because they serve different populations.”

The Colorado League of Charter Schools reports that there are currently 135,000 kids enrolled in 261 charter public schools across the state. That’s over 15 percent of total public school enrollment in Colorado; more than 50 percent are said to be students of color.

As of 2022, over 20 percent of Colorado charter school students were English Language Learners (ELLs), while only 16 percent of traditional public school students are ELLs. According to the league of charter schools, seven of the state’s top ten public high schools are charter schools. Nine of Colorado’s top twenty public middle schools are charters.

However, the La Raza model showed “no statistically significant difference between students in their math and reading annual scores — students who attended charter schools versus students who attended district schools,” Hegg says.

“It was nice to see a quantitative analysis comparing district-run schools to charter schools, because it’s hard. There’s plenty of people who have done good research on it, but it’s really tough to extrapolate how charter schools work in different states — different districts, even. So it was it was nice to see that we were able to test if there was a difference between district-run schools and charter schools,” he concludes.