Exclusive: DOJ report recommends ways to improve detainee access to lawyers in prisons

By Bart Jansen

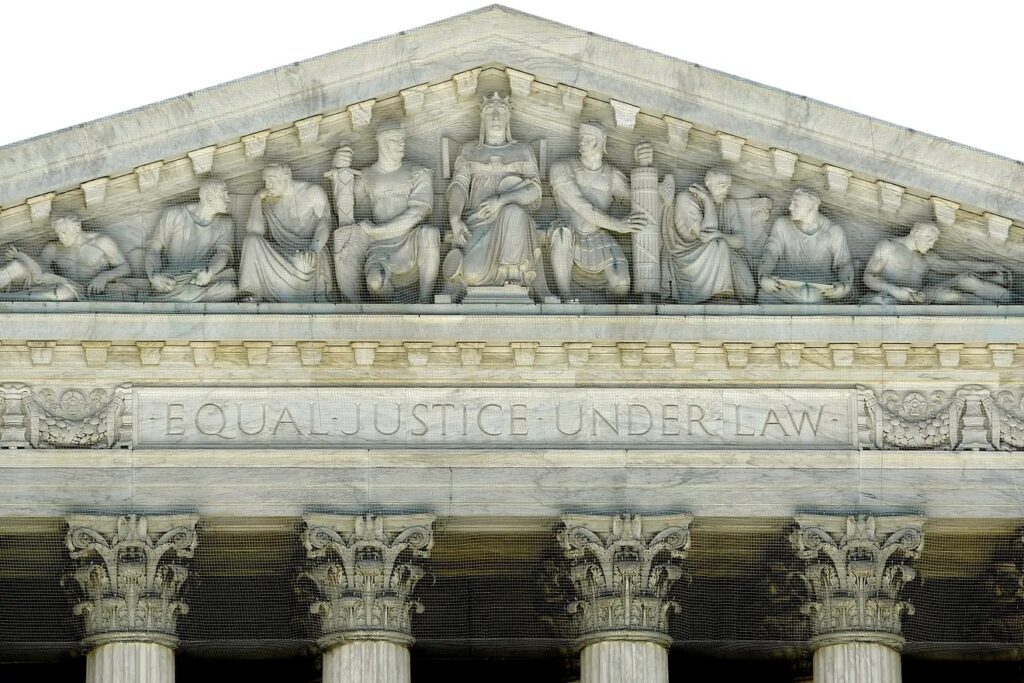

The review led by the Bureau of Prisons and the Office for Access to Justice coincided with the 60th anniversary of a Supreme Court decision that guaranteed a right to counsel for criminal defendants.

WASHINGTON – Criminal defendants hear “you have the right to an attorney” when they are arrested, but getting access easily to one in federal prison has been a challenge. New reforms may change that.

The Justice Department is releasing a report Friday with recommendations to improve the ways attorneys confer with people detained in federal prisons before trials through steps such as limiting the length of meetings, to avoid logjams in confidential rooms, and by allowing lawyers to use laptops more to review evidence.

Making it easier for detainees to meet, call and email their lawyers are among more than 30 recommendations from the review led by two department divisions, the Bureau of Prisons and the Office for Access to Justice.

Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco asked for the review in March, coinciding with the 60th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision Gideon vs. Wainwright that guaranteed defendants a right to counsel in criminal cases.

“The right to counsel is fundamental to protecting the fairness and accuracy of our criminal justice system, and the federal Bureau of Prisons plays a critical role in safeguarding this bedrock right,” Monaco said in a statement announcing the report.

Other proposals aim to boost prison staffing to facilitate communication and create a central leadership position to coordinate policies across the Bureau of Prisons.

“We’re excited because the report is very comprehensively stating we recognize these are barriers and let’s figure out solutions,” Rachel Rossi, director of Access to Justice, told USA TODAY. “Implementation is the next piece of this.”

The review featured prison wardens, corrections officers, public defenders and experts. It spanned 10 facilities, from Honolulu to New York, to gauge differences in policies across the country and what works best.

For example, eight of 10 federal detention centers have phones in common rooms programmed to call public defenders directly from common rooms. But only three facilities − San Diego, Los Angeles and SeaTak, Washington − posted numbers for detainees to call other court-approved lawyers who represent defendants unable to afford counsel.

Access between detainees and their lawyers is important because delays can lead to postponements in court decisions and longer detentions before trial. The detainees overwhelmingly have lower incomes that don’t allow them to post bail and remain free before trial.

“We need consistency and we need clear direction both to those who are incarcerated, to those who work in prisons and to counsel themselves, about what the expectations are,” Bureau of Prisons Director Colette Peters told USA TODAY.

Hurdles to access include restrictions on correspondence and limits on meeting space. Prison officials aren’t allowed to open mail, but allowing email means confirming incoming messages are really from lawyers, and providing computers for the correspondence.

“That might just seem like a no-brainer, that we could have confidential email communication,” Peters said. “But there are security implications. How do we figure out how we validate these email addresses and confirm that they are really talking to counsel on the other side?”

Meetings are another challenge. In a prison with five confidential meeting rooms, the sixth lawyer arriving to meet a detainee must wait for a room to open up. The report suggested setting a 60-minute timer on meetings, like for popular equipment at a gym.

The report also recommended adopting a calendar to schedule attorney-client visits, particularly for lawyers traveling from out-of-town, while still allowing walk-in visits. Miami is the only federal detention center that requires appointments for every legal visit. Defense lawyers said the system generally works, but can be a challenge for urgent meetings such as reviewing a plea deal.

One of Monaco’s immediate responses to the report was to designate an Access to Justice adviser to serve in the Bureau of Prisons’ central office, to deal with attorney-access issues.

“It may sound like a small thing, but it will be a game-changer,” said Rossi, a former county and federal public defender.

Differences in prison policies can also be confusing because they vary between facilities. A lawyer might be allowed to bring a laptop into meetings in one prison, but not in a higher-security facility. Monaco set a priority to promote the use of attorney laptops for reviewing evidence during prison visits and to limit the number of officials who can deny them.

One of the first changes from the review came soon after it began in March, when Monaco and members of the review group learned from public defenders that detention centers in Miami, Honolulu, Chicago and Houston were still restricting hours for legal visits because of COVID-19. Hours were expanded within days of visits to each facility, including into evenings and weekends, and all facilities have ended reduced hours for the pandemic.

Monaco asked for a plan within 45 days about how the recommendations will be adopted and additional reports every 90 days about the progress.

“We haven’t figured out how to operationalize these recommendations. They’re new. They’re hot off the press,” Peters said. “Will it all be in place Monday? No. But this is a great start.”

This piece was republished from USA Today.