Immigrant who died in Louisiana ICE detention center had filed at least 29 grievances

By Bobbi-Jean Misick

On July 13, 2023

In the months leading to his death in June, a 42-year-old man held in a privately run Louisiana immigration detention center submitted dozens of grievances alleging that he was refused medical care, denied access to his personal detention records and was subject to mistreatment and negligence by guards, records obtained by Verite show.

In one incident from August 2022, Ernesto Rocha-Cuadra, a Nicaraguan national seeking political asylum, claimed that guards at the facility allowed another detainee in the same unit to repeatedly assault him. Precise details were unclear, but it appears from the grievances that the detainee was throwing water contaminated with urine and feces at him through a food tray port in his cell. When Rocha-Cuadra asked to be moved to a different cell, he said the guards tied him up and used excessive force against him.

In an interview, his younger brother, Frank Rocha-Cuadra, said he remembered a phone call in which Rocha-Cuadra told him he’d agitated the guards by insisting he get medical attention.

“Minutes later you could hear a big scuffle. I could hear my brother just trying to fight. I could hear him taking little blows,” Frank Rocha-Cuadra said.

“I could hear his pain through the phone,” he said. “It was very upsetting because there was nothing I could do. It broke my heart. I broke down and cried.”

Ernesto Rocha-Cuadra, who had been previously deported, turned himself into U.S. Customs and Border Patrol after crossing into the United States last year, according to the records reviewed by Verite. He was then brought to Louisiana and placed in the custody of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

He was detained at the Central Louisiana ICE Processing Center, then known as LaSalle ICE Processing Center, in Jena from May 19, 2022 until last month. The facility is run by the GEO Group, a multinational private prison operator that has contracts to run ICE detention centers, as well as state and federal correctional facilities, around the country.

Rocha-Cuadra died on June 23 at Rapides Regional Medical Center in Alexandria after suffering a heart attack at the processing facility, according to ICE. Last month, The Advocate reported that Rocha-Cuadra, who was seeking a deportation delay — citing a reasonable fear of persecution or torture in his home country — had been recommended for release from the facility months before his death.

I could hear his pain through the phone.

– Frank Rocha-Cuadra, Ernesto Rocha-Cuadra’s brother

During his time at the facility, Rocha-Cuadra submitted at least 29 grievance forms all while in the facility’s segregation unit, where he spent 20 hours per day alone in his cell.

Rocha-Cuadra included more than two dozen grievance forms as part of a petition for release from detention, which he submitted to the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Louisiana in December.

Asked for comment, GEO Group responded with a blanket denial of the allegations made in Rocha-Cuadra’s grievances. ICE said “the agency takes allegations of misconduct very seriously.” Neither commented on specific allegations.

‘I’m in excruciating pain’

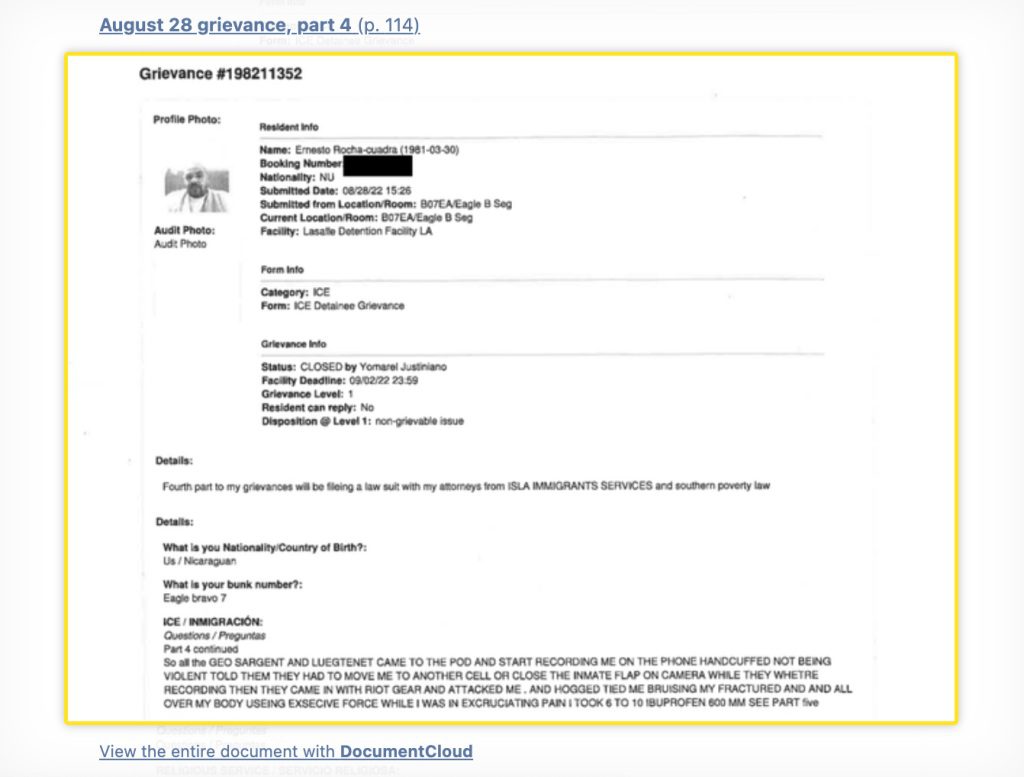

The most troubling of Rocha-Cuadra’s allegations were contained in grievance forms he submitted in late August 2022.

On Aug. 25, 2022, Rocha-Cuadra submitted a grievance about a detainee in a nearby cell.

“The GEO staff just let the inmate in cell 5 assault me by letting him throw human p— and s— on me and they will not let me go wash it off they are not letting me take a shower,” he wrote.

Litigation over immigration status is a civil matter, not a criminal one. Therefore people held in ICE detention are not inmates and the guards are not correctional officers. Of Louisiana’s eight ICE detention centers, seven are run by private companies. All of those are located in former prisons. The eighth facility, run by the Allen Parish Sheriff’s Office, is a jail. Detainees often refer to the facilities as prisons.

According to Rocha-Cuadra’s allegations, the assaults were occurring through “food flaps” in the two detainees’ cells. In a subsequent grievance form, filed on Aug. 26, he said that the guards at the facility were not listening to his demands that the other detainee’s flap be closed, despite a history of such attacks on himself, other detainees in the unit and guards.

“ICE NEED TO GET INVOLVED IN THIS MATTER,” he wrote. “I HAVE BEEN ASSAULTED twice BY THIS INMATE And GEO DOSE NOTHING TO prevent OR STOP THIS FROM HAPPENING.”

Two days later, on Aug. 28, 2022, Rocha-Cuadra submitted a series of grievance forms, about the previous day. According to his narrative, the problem with the nearby detainee had escalated, and he claimed that GEO Group guards did little to stop it. Instead, he said, they ultimately “attacked” him and restrained him when he demanded that action be taken.

The grievances from that day are only partially available in the court records. In the second form he submitted about the events of that day, Rocha-Cuadra wrote that the other detainee threw “PEE” and “S— water” in a guard’s face. The guard left to file a complaint with “police” about the incident, Rocha-Cuadra wrote, but said the alleged behavior continued — this time against Rocha-Cuadra, with some of the bodily fluids ending up in his food.

In part four, Rocha-Cuadra wrote that, while apparently in the same unit but outside of his cell, he spoke to high-ranking officials at the facility, telling them he would not return to his cell until they secured the food flap and stopped the assaults. He alleged that the guards responded with force.

Guards “CAME IN WITH RIOT GEAR AND ATTACKED ME. AND HOGGED TIED ME BRUISING MY FRACTURED [hand] AND ALL OVER MY BODY USEING EXSECIVE FORCE WHILE I WAS IN EXCRUCIATING PAIN. WHILE I WAS IN EXCRUCIATING PAIN TOOK 6 TO 10 IBUPROFEN 600 MM,” he wrote.

The incident aggravated an old injury to his hand. He sustained the injury in April 2022 while being transported from an ICE staging facility in Alexandria to Richwood Correctional Center, another immigrant detention facility in Louisiana that is run by private prison company LaSalle Corrections. Medical records obtained by Homero Lopez, legal director at Immigration Services and Legal Advocacy, and Rocha-Cuadra’s immigration attorney, from his time at Richwood show that he was treated for an injury to his right hand and wrist.

Rocha-Cuadra was transported to Rapides Regional Medical Center. He wrote that staff “THREW ME IN THE SUV AND ME HITTING MY HEAD AND THEY THREW ME IN SHACKLED FROM HEAD TO TOE ON MY BACK AS THE CAMERA WILL SHOW VOMITING AND CHOKING ON MYSELF .. THINK I WAS GOING TO DIE.”

Medical records note the visit to the emergency room at Rapides Regional Medical Center on Aug. 27, 2022 for “ingestion of substance,” specifically an overdose of ibuprofen. A doctor’s note from the hospital said Rocha-Cuadra reported that he had taken 14 or15 ibuprofen that day to treat chronic pain.

The doctor wrote that Rocha-Cuadra said he felt nauseated and had vomited, which is consistent with what he wrote in his grievance form. It mentioned the injury to his hand, calling it a “wrist fracture in April that was not treated per patient.” It also mentioned pain around his ankles, “where the handcuffs are on him.”

The doctor wrote that Rocha-Cuadra said he had been “jumped and kicked in the head, back and chest.” The note said officers denied assaulting him, saying Rocha-Cuadra was held on the floor for being “non-compliant.”

By late afternoon the day after the hospital visit, Rocha-Cuadra wrote that he was still in pain.

“IT IS NOW 4PM. AND HAVE NOT RECEIVED ANY MEDICATION,” he wrote. “I’M IN excruciating pain … Need ICE help.”

When asked via email about Rocha-Cuadra’s claims that GEO staff allowed a fellow detainee to toss urine and feces contaminated water onto Rocha-Cuadra and that staff later assaulted him, Christopher Ferreira, a spokesperson from GEO Group, said, “We strongly deny these baseless allegations. We are unable to provide comment regarding specific cases related to individuals in the custody of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which would include any grievances filed by such individuals.”

The records show that the Aug. 28 complaints were closed on Aug. 30, 2022 by Yomarel Justiniano, who works as a deportation officer for ICE.

“We received the videos, everything was documented and your grievance is unfounded. Please see medical if you are not feeling well. Please know that this messaging system is not to be abused with 9 plus grievances of the same issue. ”

Justiniano labeled the grievances a “non-grievable issue.”

Reached for comment, Sarah Loicano, a spokesperson from the New Orleans ICE Field Office, provided a statement that did not directly address Rocha-Cuadra’s allegations.

“U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is committed to ensuring that all those in its custody reside in safe, secure, and humane environments under appropriate conditions of confinement,” Loicano said in an emailed statement. “The agency takes allegations of misconduct very seriously – personnel are held to the highest standards of professional and ethical behavior, and when a complaint is received, it is investigated thoroughly to determine veracity and ensure comprehensive standards are strictly maintained and enforced.”

History of mental health issues

Rocha-Cuadra had a long history of mental health problems, and those were exacerbated by his time in Jena, his attorney told Verite.

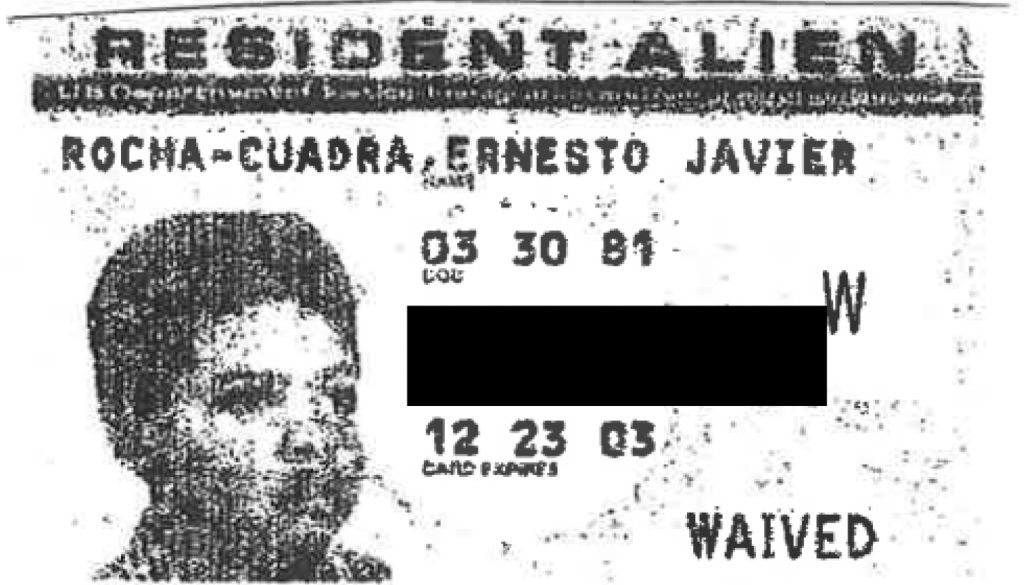

According to details in his habeas corpus petition, Rocha-Cuadra first entered the United States with his family as a child in 1988 and was granted political asylum in 1989.

He became a lawful permanent resident in the early 1990s, records in his petition show. But he was deported in 2009 after convictions on charges related to burglary in 2002 and petty theft in 2005.

Rocha Cuadra re-entered the United States near Yuma, Arizona in early April last year, attempting to seek political asylum. He was deemed eligible for withholding of removal under the convention against torture, which has a higher threshold to receive protection but keeps recipients from being deported and allows them to work in the United States. Before his death he was seeking to be entered into regular asylum proceedings.

Lopez was appointed to be his counsel by an immigration judge because Rocha-Cuadra was deemed mentally incompetent due to post traumatic stress disorder. It is documented that Rocha-Cuadra was tortured while held in jail in Nicaragua, after he was deported. Lopez reviewed videos of hearings from Rocha-Cuadra’s 2009 deportation and concluded that he may have been experiencing some cognitive difficulties even then. His brothers believe he already suffered from PTSD from his time in jail in Southern California.

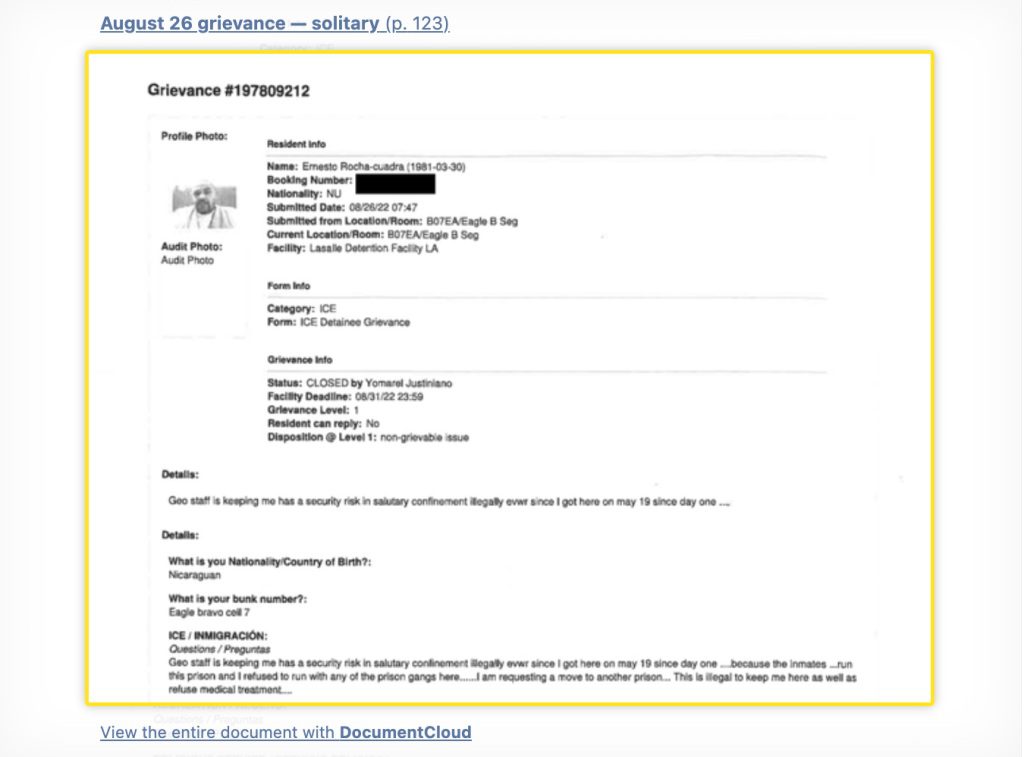

Along with his grievances about specific incidents, like the one that ended with the hospital visit last year, Rocha-Cuadra also complained about the general conditions of his confinement in Jena. According to the records obtained by Verite, as well as interviews with attorneys who worked with him, he was held in a restrictive segregation unit the entire time he was there.

In a grievance on Aug. 26, 2022 Rocha-Cuadra wrote, “Geo staff is keeping me has a security risk in salutary confinerentillegally [ever] since I got here on may 19 since day one.”

“I am requesting a move to another prison,” he wrote.

In notes from a phone screening with the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Southern Immigrant Freedom Initiative attorney Rose Murray, Rocha-Cuadra said he had been placed in the segregation unit for protection due to suspected gang affiliations. He said he was not gang affiliated. He described the unit as a cell block with 12 cells, each with two beds, although they house one detainee at a time. He said people in the segregation unit were given two hours of free time outside of their cells in the morning and in the evening for a total of four hours.

Occasionally, Rocha-Cuadra was even further isolated, placed into solitary confinement for alleged disciplinary infractions.

“We do know he was repeatedly placed in disciplinary solitary confinement,” Lopez said in an interview.

Lopez said that people placed on disciplinary segregation, even for non-violent infractions, were handcuffed whenever they were outside of their cells and were not allowed to convene with other detainees, even during meal time. He said in his in-person and video meetings with Rocha-Cuadra, his client was often handcuffed.

Lopez said Rocha-Cuadra had a strong grip on reality but would become quiet or drift off at times during their meetings. He said the longer Rocha-Cuadra remained in detention the more his mental health seemed to deteriorate.

“He would make references. I would push him on it. He’d blank out and then say, ‘OK where were we?’ or ‘I need a rest,’” Lopez said.

‘There has to be an answer somewhere’

Medical records related to his June 23 death from a heart attack said Rocha-Cuadra was found unresponsive in his cell and was taken to a nearby hospital. He was initially stabilized but later died, the records say.

Frank and Ronny Rocha-Cuadra, another of his brothers, have expressed suspicions regarding the death. They both maintain that there are no known heart issues in his family’s medical history.

“There has to be an answer somewhere,” Ronny Rocha-Cuadra said. “I don’t care what it takes. I’m going to keep looking into this.”

Ronny Rocha-Cuadra was concerned when he learned that his brother was categorized as obese when he died. He said his brother weighed roughly 160 pounds when he re-entered the United States in April 2022. Medical records list his height between 5 feet 5 inches and 5 feet 6 inches. A medical record from Richwood Correctional Center lists him weighing 177 pounds on May 6, 2022. A medical record from June 23, 2022 listed his weight at 195 pounds – a nearly 20-pound increase in weight in less than two months.

On June 12, 2023, he was listed as weighing 263 pounds.

Ronny Rocha-Cuadra wondered how his brother’s weight could change so quickly.

“He was never a big person,” he said multiple times.

On May 3, 2022, while Rocha-Cuadra was still at Richwood Correctional Center, X-ray findings revealed, “The heart is normal in appearance,” according to a patient record obtained by Lopez.

Lopez suggested that extended detention contributed to Rocha-Cuadra’s deteriorated physical health.

In November 2022, an ICE panel recommended that Rocha-Cuadra be released from detention. However, he remained in detention until his death. Ernesto Rocha-Cuadra’s family held a memorial service for him in Southern California on Saturday (July 8).

Speaking over the phone through tears, Frank Rocha-Cuadra called his older brother a father figure and a protector. The boys’ father worked as a truck driver and was away a lot. Frank Rocha-Cuadra said his brother always looked out for the family.

“He kinda showed me how to become a man and [be] responsible,” Frank Rocha-Cuadra said.

He said when Rocha-Cuadra worked in the custodial department at Biola University in California he would bring food from the school’s cafeteria home to feed the family.

Ronny Rocha-Cuadra said his brother would often walk his elder cousin, a woman, home from work when she got off at night.

“He was always looking out for people,” Ronny Rocha-Cuadra said.

Ronny Rocha-Cuadra said his brother was always a hustler. He remembered when they were children, Rocha-Cuadra realized that Pogs, cardboard game pieces from the 1990s, were as thick as quarters.

It was his brother’s idea to “cut ‘em in[to] quarter size and go to the candy machines and get the candy from the machine,” Ronny Rocha-Cuadra said.

This piece was republished from the Louisiana Illuminator.