‘Indian orphan nobody wanted gets parents’: The dark history of the Indian Adoption Project

By PJ Randhawa

On June 23, 2023

In 1958, as the US government began to shut down Indigenous boarding schools, they developed another way to assimilate Native children into white society.

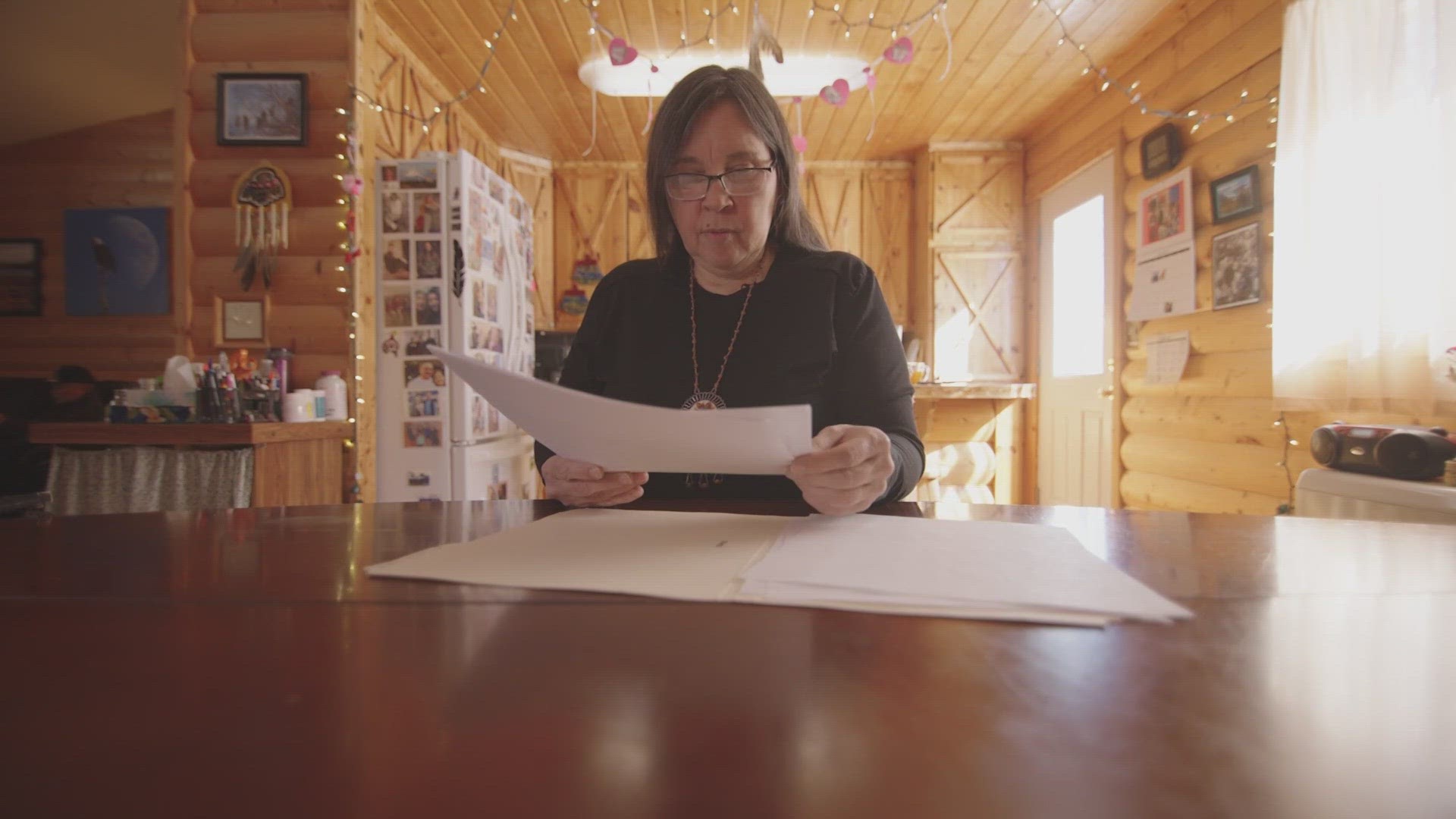

Anecia Tretikoff is a lost link, off a broken chain

“My mother had no support and no family connections. She cried and cried while signing the [adoption] papers,” said Tretikoff.

In 1961, Tretikoff was put up for adoption moments after being born in a Seattle hospital. She was born into a family fragmented by the U.S. government’s Indigenous boarding schools.

“My mother and her family were separated in the boarding school. The connections to the village were largely broken due to the boarding school experience and being 1,000 miles from her village,” said Tretikoff.

Just like her mother, Tretikoff’s life would soon be shaped by another dark chapter of American history.

The Indian Adoption Project.

In 1958, as the US government began to shut down Indigenous boarding schools, they developed another way to assimilate Native children into white society.

Kalispel tribal attorney Lorraine Parlange explains.

“Agencies, both private agencies and public agencies, began this project of about 16 western states, removing children from Indian parents and placing them on the east coast of this country, predominantly with white families,” said Parlange.

They called it “The Indian Adoption Project.”

“There’s this goal of assimilation and really cultural genocide and termination of tribal units, tribal families, tribal governments and their culture,” said Parlange.

“White Parents for Indian Orphans” read the headline of the St. Louis Post Dispatch in 1968. Underneath- a crude cartoon of children in Native regalia performing a dance around a cowboy.

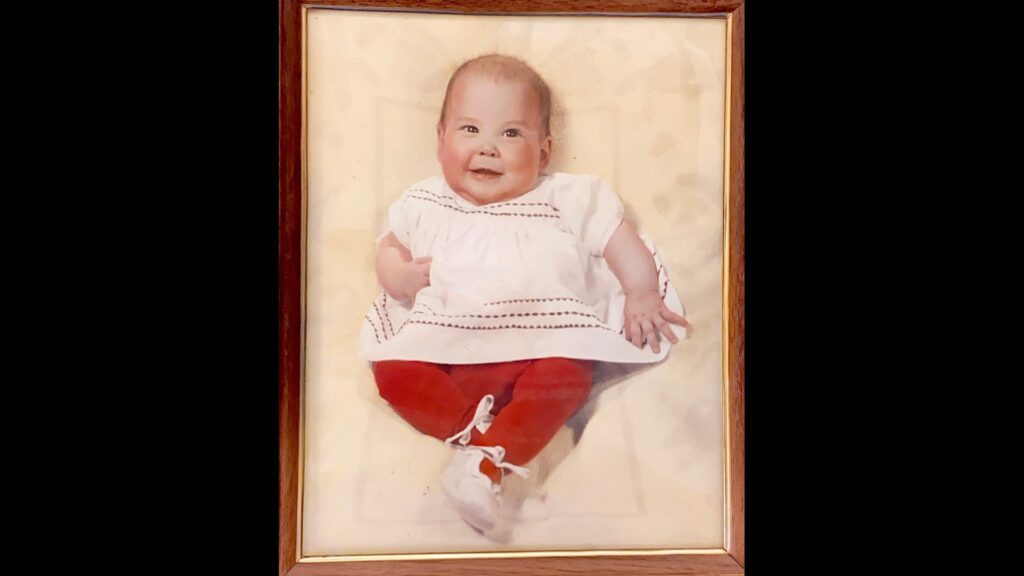

The Indian Adoption Project ran from 1958 until 1967. Experts say the initiative separated thousands of children from their families. Tretikoff was one of those children. She was adopted into a Christian family in Olympia as a newborn.

“I was led to believe that by virtue of my birth, I was a damned sinner damned to hell, and the best I could do is to be very good, and then I could have a cooler place in hell,” said Tretikoff.

To Treikoff, it was a world of blond hair and blue eyes, “and then I look in the mirror. and I am shocked, I am ugly, and I don’t fit and I try not to look in the mirror.”

“Propaganda”

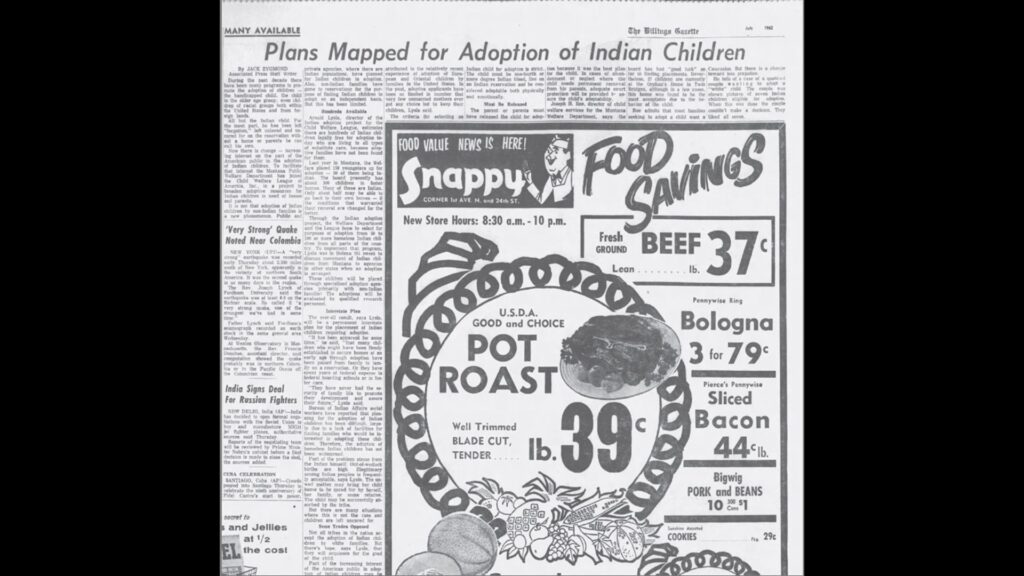

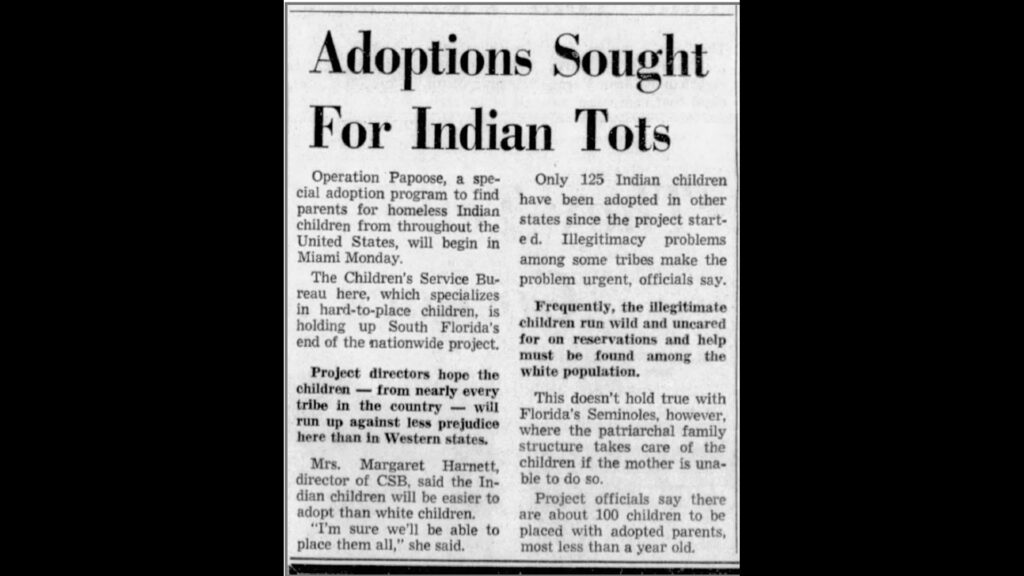

Advertisements and news stories from the time paint a much different picture of life as a Native adoptee.

A headline from an article in the Des Moines Register in August 1964 proclaims “Indian Boy, 3, Finds No Prejudice in Hampton.”

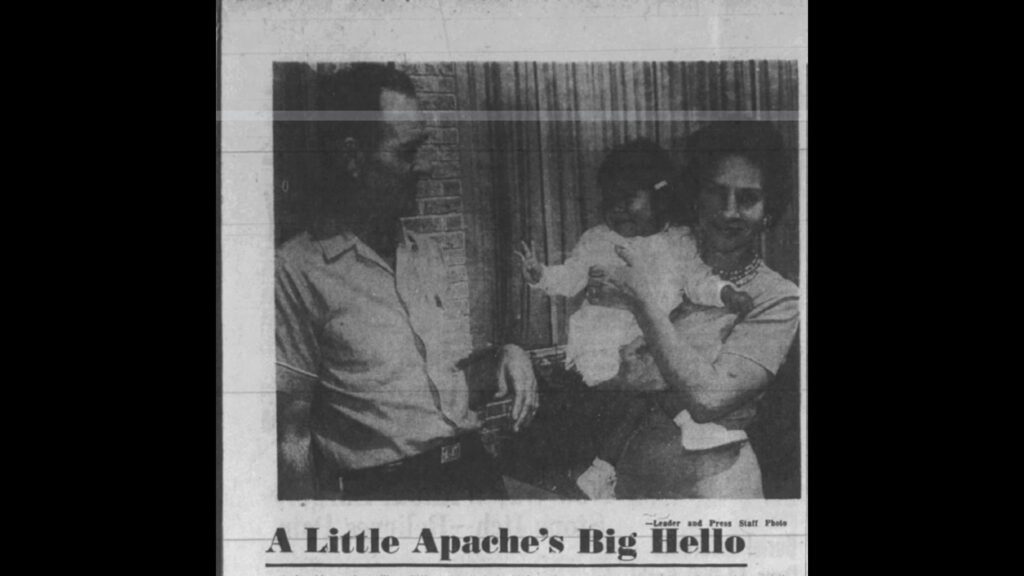

While dozens of other newspaper articles from the time show images of doting Caucasian parents holding newly adopted Indian children with headlines like “A Little Apache’s Big Hello.”

“Racist terms. Oh, fantasy! What utter fabrication,” said Tretikoff after reading several articles from the ’50s and ’60s detailing adoptions under the initiative.

Other articles from the era downplay the difficulties many Native adoptees would face. A headline for a 1968 article from The Daily Oklahoman reads “Adopted Indian Children Fit Easily into White World.”

“Oh my god,” said Tretikoff upon reading the articles. “I’ve never ever associated my adoption with the word welcome or acceptance. I had never felt accepted in that family. In my neighborhood, in my school, in our community. I was the only brown person.”

Stolen from home

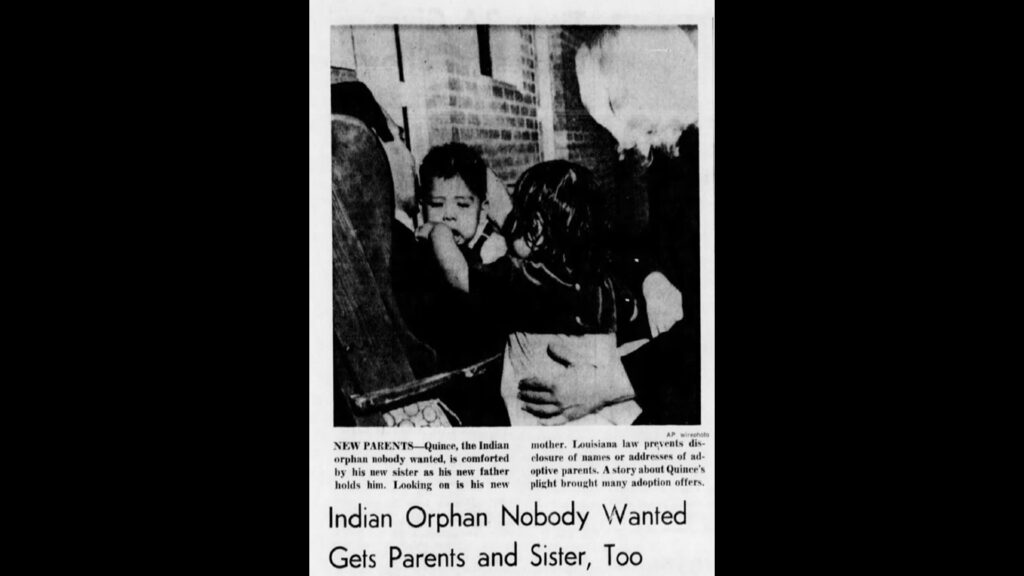

In the ads and articles, Native children were described as ‘unwanted’ or ‘neglected’ by their Native families. Headlines from the time include: “Indian Orphan Nobody Wanted Gets Parents and Sister Too,” and “Once Unwanted Indian Child has Long List of Prospective Parents.”

Experts say that was often far from the truth.

“I’ve talked to other tribal members who have discussed social workers showing up on the front lawn and taking children, not going in and talking to the adults that were present, just removing them from the front lawn and leaving, there was not an accountability,” said Parlange. “Many of [the children] had many family members still alive, who would gladly have had, would have wanted to have been part of their life.”

“It’s really… I… I’m angry,” said Tretikoff. “I feel very sorry for those children.”

Adopting an Indian child: The “in” thing to do

“[The articles] talk about [how] you could have an Indian child… for $10,” said Parlange. “It is pretty, pretty hard to read and to see. But clearly, there was the overall discriminatory and racist attitude was prevalent, strongly prevalent at that time.”

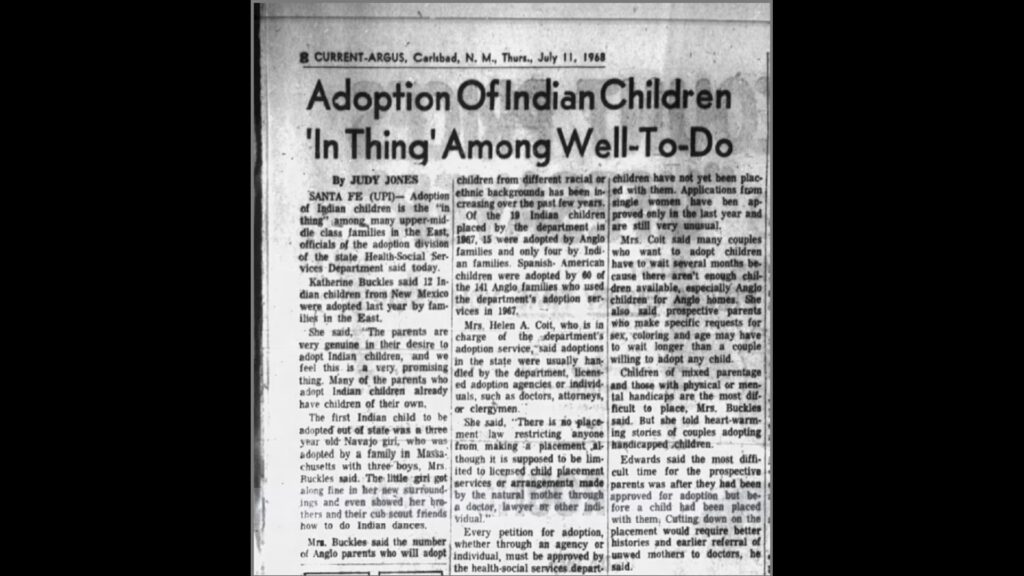

Some articles even promoted adopting Indian children as the “in thing” to do among the upper class.

“A saving of the children was some of the sales pitch. The families that were doing the adoption were portrayed as the enlightened people that were willing to have these children in the home,” said Parlange.

“This is pretty much nauseating. From that, it’s so far from the truth and it is told in a way to manipulate and I mean, it’s propaganda,” said Tretikoff.

Finding Home

It wasn’t until Tretikoff entered college that she saw another Native person for the first time. She says she felt a sense of instant belonging.

“I was stunned, shocked, adrenalized. And I just stared at her this poor girl. And she seemed to have some recognition of me,” said Tretikoff.

Yet a deeper recognition was still absent from her life. In her 20s, Tretikoff was finally able to access her adoption records and track down her birth mother in Alaska.

“We just like magnets, embraced each other and just hugged and held each other and we just cried and cried and cried,” said Tretikoff. “It was just soaking in identity, really for me.”

She learned her true identity, Alutiiq Sugpiaq, which is one of eight Alaska Native peoples.

Decades later, a new job brought Tretikoff home to Alaska permanently, where she met and married the love of her life.

“He is my Alutiiq-Sugpiaq soulmate. And he says, ‘Where have you been all my life?’” said Tretikoff. “I think it’s just delightful and that he grew up eating traditional foods that he and his siblings and his mother and his father, harvested, gathered, processed and put up is just a rich, rich thing to have in one’s soul. How wonderful that must feel to feel settled in one’s home with people that look like you.”

Connected

No longer a broken link, Tretikoff is now connected to a culture and history once ripped from her and so many others.

“There’s so many smiles and there’s so many hugs and there’s so many eye to eye, heart to heart, feelings of ‘I see you’. And there is an incredible amount of healing that comes from ‘I see you’ after being invisible and unseen for the majority of my life.”

Protections in place

The Indian Adoption Project ended in the late 1960s as Native American activists and allies ramped up their fight for civil rights and equality. Their efforts paid off- a few years later, the “Indian Child Welfare Act” was passed by Congress, which made adopting native children to non-native parents extremely difficult.

That act was just upheld by the US Supreme Court earlier this month.

This piece was republished from King News 5.