Massachusetts Is Poised to Make Communications Free for Incarcerated People

By Alex Burness

On August 4, 2023

The reform would eliminate the exorbitant charges people face to keep in touch with loved ones in jail and prison, removing a heavy financial burden for thousands.

Annalyse Gosselin would like a new coat. Hers is ripped, and its zipper doesn’t work anymore.

She’d also like a new phone and to eat at a restaurant one of these days—the last time she dined out was in May, on her 20th birthday—but can’t afford those things either. Gosselin works two jobs, at a grocery store and part-time as a nursing assistant, but she says that nets her less than $20,000 a year. That isn’t nearly enough to thrive where she lives in Boston, where the median one-bedroom apartment rents for about $3,000 a month.

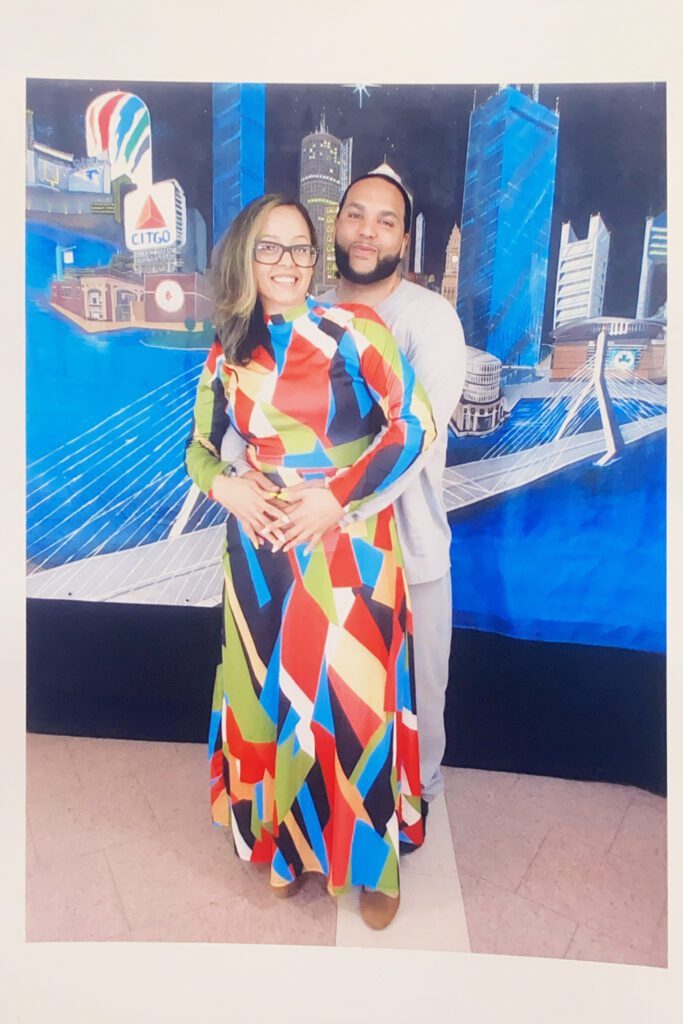

Fifteen months ago, she started a relationship with an imprisoned man she’d been corresponding with through a pen pal program that connects incarcerated people with concerned strangers. Now budgeting is even harder: her boyfriend, Syrelle, is held in Norfolk, 30 miles from her home, and keeping in regular touch with him is enormously expensive. It costs about $2.50 to talk with him for 20 minutes on the phone, and twice that if they do a video call. Emails cost 25 cents apiece. The private company the prison system uses to run communications takes a $3 surcharge every time she adds money to her account.

Gosselin says she’s spent about $5,000 just to talk with Syrelle since the start of their relationship, and roughly the same amount on purchases for him at the prison commissary: an extension cord, a small television, chicken, vegetables, medicated protein shakes.

“I go broke, literally. I make my bank account negative,” Gosselin told Bolts. “I don’t do much for myself; I just do for him. My mom and everybody always tells me, ‘You can’t keep making sacrifices for your relationship.’ But who else is going to do it?”

Massachusetts is now poised to ease that financial burden for Gosselin, as well as for the thousands of people held in the state’s prisons and jails, and their loved ones. Lawmakers just approved reforms on Monday that would eliminate charges for communicating with incarcerated people. It would also limit commissary markups in all jails and prisons to 3 percent above an item’s purchase price.

Gosselin says making communications free would change her life. She’d be able to speak with her boyfriend without watching the clock or her wallet. “It will honestly be the best thing,” Gosselin said. “It just feels like a burden taken off my back once it happens.”

The reform, which is part of the state’s annual budget, now awaits the signature of Governor Maura Healey, a Democrat who has expressed support for the change and is expected to approve it. Her predecessor, Republican former Governor Charlie Baker, denied a similar proposal last year.

If Healey does approve this change, Massachusetts would be the fifth state to make prison phone calls free. Connecticut in 2021 became the first to do so, followed by California in 2022 and Colorado and Minnesota earlier this year. Several large U.S. cities have also mandated free phone calls for people in jails, starting with New York City in 2018 and followed by Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Miami, among others. Last year, Congress also passed a law granting the Federal Communications Commission new and greater authority to regulate the high cost of calls to and from incarcerated people.

The Massachusetts reform would be among the most wide-reaching: The state would join only Connecticut in making communications of all kinds free for all incarcerated people—that is, not just phone calls, but also video, email, and messaging. Massachusetts would pay for the communications out of a $20 million state trust fund meant specifically to cover those costs.

The changes were guided in large part by the advocacy of people directly harmed by the exorbitant costs of communicating with loved ones in prison. For instance, many of those people expressed worry that some facilities would respond to free communications by further restricting the amount of time people can spend on phone or video calls—indeed, Healey’s initial budget proposal called for just such a cap, and also excluded jail communications. Advocates told Bolts that incarcerated people helped add a provision to the current budget prohibiting jails and prisons from limiting communication access beyond their existing policies as those services become free.

“We’re feeling extremely happy with the language that came out of the legislature,” Jesse White, policy director at Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts, told Bolts. “Not only will phone calls be free, but also access should not be reduced.”

Many people now cheering the prospect of free prison phone calls once thought such reforms would never happen. Jarelis Fonseca, whose partner is incarcerated in Norfolk and who says she spends more every month on prison communications than on her car insurance, rent, and groceries combined, told Bolts she long ago accepted that extreme costs come with the territory of having a loved one in prison.

“It’s something we feel like we just have to deal with, and deal with by ourselves,” she said. By becoming active in advocating for the Massachusetts change, she added, she’s come to understand how common her struggle is.

“I was like many families: in the dark. I knew what I knew from what I pay and how much it cost for me. Many people are not able to talk about it,” she said. “We’re all deciding what we’re going to go without, putting things off, to add money to continue to speak to our loved one. It’s stressful.”

In recent years, a groundswell of activism has coalesced around cutting the high costs of communicating with people behind bars. Bianca Tylek, executive director of Worth Rises, an abolitionist organization helping lead a nationwide movement for free prison and jail communications, says organizers wanted to help incarcerated people and their loved ones while also chipping away at the network of private companies that profit off them.

“Our strategy, when we started this work in 2017, was that we had to start somewhere,” Tylek told Bolts. “If we’re going to dismantle an industry—one that very few people know anything about—we have to start somewhere that feels accessible.”

Worth Rises estimates that prison telecommunications companies make nearly $1.9 billion annually from contracts with jails and prisons. That money goes mostly to a small group of private equity-owned corporations, but those corporations typically send kickbacks to governments who award them exclusive contracts. For instance, before Colorado made prison phone calls free, the state received up to $800,000 per year from the company Global Tel*Link for rights to run the prison system’s phone program.

Tylek says organizers highlighted the exorbitant cost of prison phone calls because they thought it would resonate with others. “I don’t think there’s anything more accessible than a simple phone call,” she said. “A phone call to your mom, to your child, to your partner. That seemed like something we could explain to people: that children deserve to hear ‘I love you’ whether or not their parent can afford a phone call.”

Tylek says there’s legislation planned for next year in Hawaii, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, Washington and Wisconsin, and that advocates are actively organizing for reforms in a half dozen other states. She says organizers hope to make at least prison phone calls free in every state by 2027.

Free communications may well enable even more advocacy from incarcerated people in Massachusetts, who could participate remotely in policymaking at no cost if prison calls are free. As this reform nears the finish line, organizers are already working on other legislation to loosen restrictions on in-person visitation that the prison system implemented in 2018.

James Jeter, director of Connecticut’s Full Citizens Coalition, said he’s been able to dramatically expand his advocacy network since his state made calls free in 2021. That reform led to an immediate doubling of both total phone calls by incarcerated people in Connecticut and of average call duration, CT Insider reported.

“We had this idea that once the phone calls went free, we could actually start in the prisons, educating guys in there on how to be advocates to their families, to run a phone-banking campaign through the incarcerated and their families,” Jeter, who is formerly incarcerated and whose organization is working toward full enfranchisement for all people in Connecticut with felony convictions, told Bolts. He added that his coalition now sends about 400 emails into the state prison system every day.

“We’re having conversations with people that we would otherwise have no access to,” Jeter said.

In this way, Tylek said, the movement to make communications free is already building on itself.

“We plan to get people from talking about prison telecom to talking about how we get into financial services or food or health care or commissary. Talking about telecom has allowed us to talk about exploitation more broadly,” she said.

For now, in Massachusetts, those most closely affected by the big business of calling home are hoping for financial relief and also closer connection to their loved ones behind bars. Research has consistently shown that maintaining close ties with family and friends is critical not only in improving outcomes for people while incarcerated, but also in giving those people a better shot at success once released.

Fonseca says she calls the prison about five times a day to talk with her partner in hopes that he feels connected to home. “For him and for anyone incarcerated, we know that when people feel incorporated still to their family and friends, they’ll do better when they’re in there and they’ll do better when they come out,” she said. “It’s about him knowing he’s supported, that sacrifices are being made for him, because he’s worth that.”

Joanna Levesque has also been stretching her budget to keep in touch with her partner, who is incarcerated in a prison in Bridgewater, Massachusetts. “It’s amazing what the consistency of having someone to talk to does for someone’s mental health,” Levesque said. “Nobody wants to be alone.”

“It makes little sense to me that the cost of phone calls for inmates is so insanely high when the vast majority of us are indigent,” Levesque’s partner, Christopher O’Connor, told Bolts by email. “I often feel so bad for being a financial burden to my friends and family.”

Levesque says she hopes free calls allow them to remain close and also enable her to live more comfortably, including by eating breakfast and lunch more often. At the moment, she told Bolts, she works multiple jobs and prioritizes communication with her O’Connor over her own wellbeing—which, she says, means long stretches of fasting.

“I am so beyond excited,” she said.

This piece was republished from Bolts Magazine.