Nearly one in five state prisoners go directly from maximum security to the street

By Jenifer B. McKim and Margot Amouyal

On November 7, 2023

Jenifer McKim GBH News

Jamaul Vital says he was restricted to a cell for at least 20 hours a day while incarcerated at the state’s maximum security prison in Lancaster for more than two years.

The 28-year-old Lynn man remembers his last night behind bars — pacing in his cell, listening to the yells from nearby prisoners. And then, in what still seems like a blur, Vital was escorted — in chains, still wearing his prison-issued shoes — out of the Souza-Baranowski Correctional Center and onto the street.

Vital is one of about 3,000 prisoners who were released directly from a state maximum-security prison since 2013, an average of 289 a year, according to state data obtained by the GBH News Center for Investigative Reporting. These prisoners have far fewer opportunities than lower-security inmates to participate in programs and classes that prepare them to succeed upon their release.

Now all Vital wants to do is bond with his 22-month-old son, get a job and stay out of trouble. He knows the odds are against him.

“The statistics speak for themselves. Everybody goes back in,’’ Vital told GBH News recently. “I’m not a monster. … All the trauma that I’m going through, I feel like I have a lot to lose, even more now.”

The state’s goal, prison officials say, is to make sure prisoners have time in lower-security institutions like pre-release and minimum-security institutions in the months leading up to their release. In those types of facilities, prisoners may have access to public transportation and be able to work outside the prison walls.

But state prison officials say some prisoners “disqualify themselves … because of the significant disciplinary record incurred during their incarceration,” according to a written statement. Others who are included in those tallies are parole violators who are housed at Souza for shorter stays, the state says.

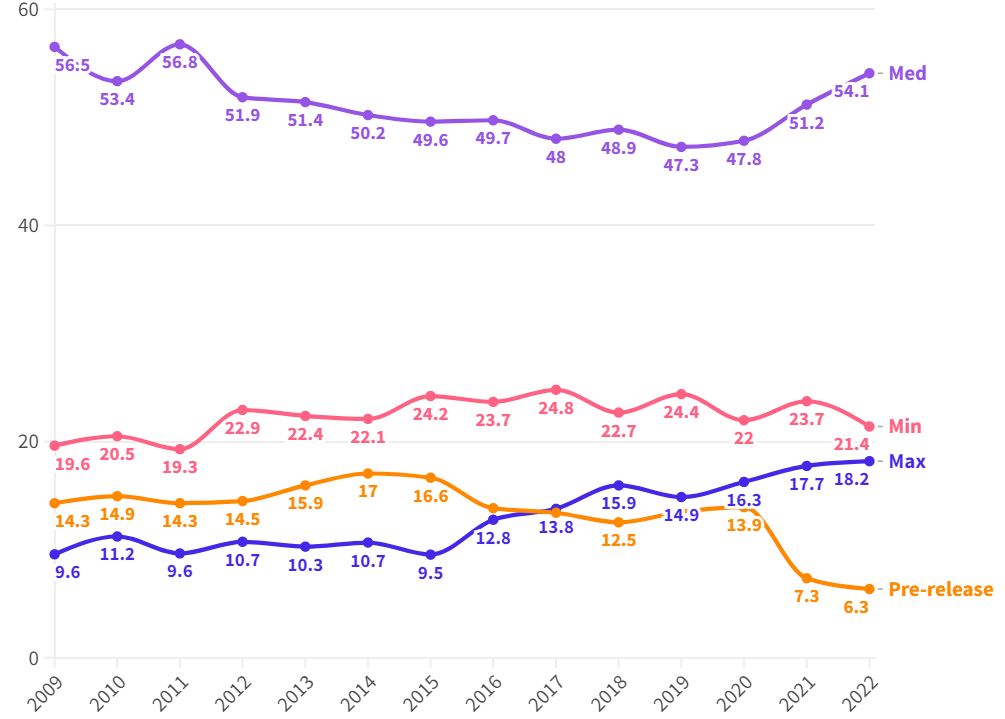

As the prison population has dropped dramatically, a greater share is being released directly from high-security prisons. Last year alone, the state released 249 prisoners from the state’s highest security prisons, representing 18% of all prisoners released from the state Department of Correction, data shows — about twice the rate of a decade ago.

Visualization by Lisa Williams / GBH News

Prisoners’ advocates say these numbers reflect deep flaws in the state system that puts formerly incarcerated people, and the public, at increased risk.

Rates of recidivism are higher for those released from maximum-security prisons — 40% of prisoners released from maximum security in 2018 were re-incarcerated within three years, state data show, almost twice that of people who complete their sentences in minimum-security or pre-release programs.

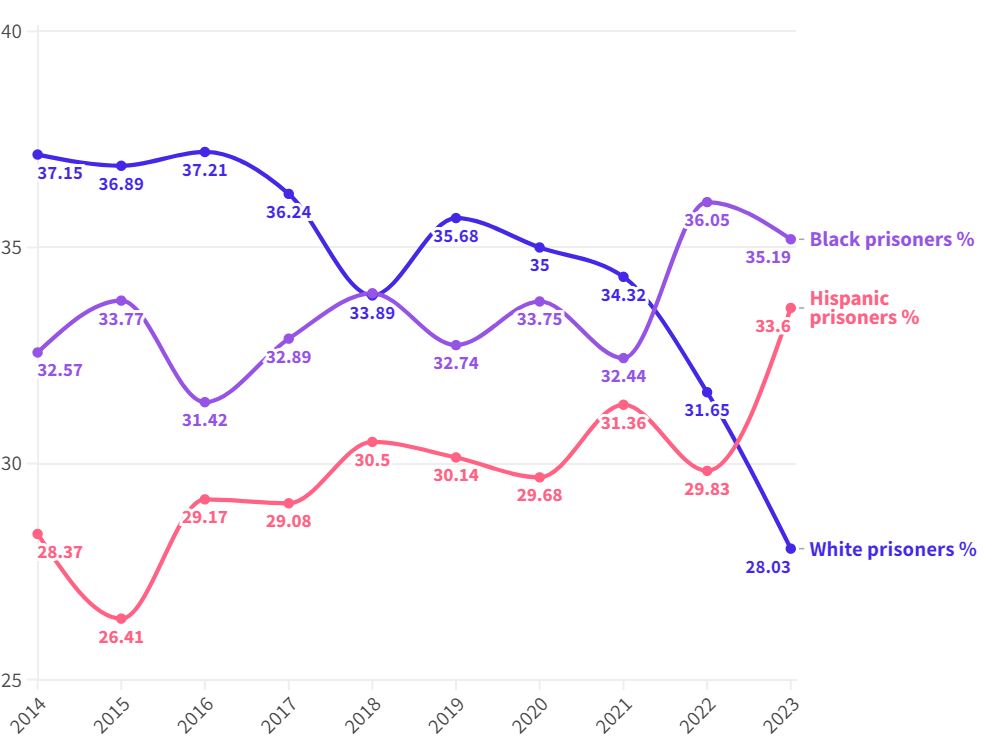

Numbers also point to racial disparities. Black and brown prisoners like Vital are more likely to be classified as high risk and incarcerated in higher security prisons than white prisoners and less likely to be in pre-release programs according to data obtained by GBH News.

Mac Hudson, a formerly incarcerated person now working for the nonprofit Prisoners’ Legal Services in Boston, says the state has historically over-classified prisoners of color to keep beds full in more costly, higher-security prisons in a system with a budget of some $780 million. Hudson says he’s been helping Vital find work and get involved in community support programs because he’s seen too many formerly incarcerated men from Souza end up homeless, addicted to drugs or dead of an overdose.

“When these people get out and they’re unprepared,” he said, “and they create this harm, who’s responsible? We are, as a society.”

Jenifer McKim GBH News

Massachusetts’ prison population is now about half of what it was in 2012. It now costs the state more than $125,000 to house and provide services for each of its estimated 6,200 prisoners, state data shows. Advocates say the state should spend more money on programming and re-entry and less on keeping prisoners in toxic situations.

“You have people locked in their cells, traumatized,’’ said Bonnie Tenneriello, a senior attorney at Prisoners’ Legal Services. “People are not getting programming that they need to succeed on the street. Souza Baranowski lacks a wide range of programming. And then we’re putting them out the door and telling them to go find a job. It’s a recipe for failure.”

Manuel Eusebio told GBH News in August that he, too, was released from Souza earlier this year — completing a five-year sentence surrounded by men serving life sentences without parole. He said his shorter sentence made him a target.

The transition also was a challenge, he said, because the strict controls on his life in the state prison contrasted so dramatically to his life on the outside, where he is expected to find a job and housing — all made harder by his criminal record.

“They limit your showers, they limit everything, they limit your phone calls,” he said. “They don’t prepare nobody.”

Jenifer McKim GBH News

The consequences for other members of the public, too, can be fatal. A 2016 state report shows that people released directly from maximum security facilities are more likely to commit violent crimes. Since that year, at least three people released from Souza were convicted of murders committed months after their release, according to a GBH News search of online media. These include the case of Kelvin Vickers, who was convicted in October of killing three men about two months after his release from Souza.

Ben Forman, research director for the Massachusetts Institute for a New Commonwealth, or MassINC, says he and others have long been pushing to reduce the number of prisoners released directly from maximum security prisons. He referenced a 2004 report submitted to then-Gov. Mitt Romney detailing how many prisoners, “walk directly out of a maximum security facility onto the street” — a practice he calls a “ticking time bomb.”

“I don’t know if there’s a better word for it than madness,” Forman told GBH News recently. “Idon’t know why we don’t pass a law that says that you can’t take that route back to the community, and there has to be some sort of step-down process to give people the ability to relearn how to be self-sufficient.”

‘I didn’t have a chance’

Vital has a round face covered in tattoos, designs he says he started to amass as a teen growing up in Lynn. He was first brought into the criminal justice system at the age of 11 after he said he assaulted a teacher with a pencil. He was frustrated because he didn’t understand the math and other kids made fun of him. “That was a turning point in my life,” he said.

Vital describes years of living in Department of Youth Services facilities as well as a series of foster and group homes. At 19, he was convicted as an adult of gun and drug charges and sent straight to a maximum-security prison.

“You think that an 18-year-old or 19-year-old should be in a maximum-security prison with grown men?” he asked. “I never had a chance.”

State officials say the Department of Correction uses an “evidence-based, objective, point-based system” to classify prisoners into the appropriate level of security. But there is growing concern that the system is racially biased. Authors of a 2022 report on structural racism submitted to the state Legislature pointed to the practice of using a prisoner’s youth, lack of education, and/or employment history to keep them in higher-security prisons — when young Black and brown people are more likely to be arrested and sentenced. “Race disparities in the external criminal justice system outside the walls are imported into Corrections,’’ the report concluded.

Jason Dobson, a spokesman for the Department of Correction, said last week that the state is partnering with the UMass Chan Medical School to examine whether the classification system used across the country contributes to racial disparities and seek improvements. He said the state has one of the lowest recidivism rates in the country and has managed to reduce re-incarceration rates for those who require maximum security over time.

The demographics of maximum security in Massachusetts has changed dramatically in the last 10 years

Visualization by Lisa Williams / GBH News

“We remain deeply committed to the continued implementation and expansion of education, vocational training, and programming that we know leads to lasting rehabilitation,” he said.

Vital — who is half Black and half white — says he was terrified when he was first sent to a now-closed maximum-security prison in South Walpole, housed next to rival gang members and adult men convicted of life sentences without the chance of parole. “Within the first day on a unit, I had a knife. I’m 19 years old, scared to death, but I can’t show it,” he said.

His three-year conviction expanded to seven and a half, he says, because of punishments he amassed in prison involving fights with other prisoners and correctional officers. In 2020, he was released on probation — also directly from Souza, now the state’s only maximum-security prison. A year later, he was re-arrested after being found asleep at the wheel of a parked car. Boston Police found drugs and a gun; Vital is fighting the charges, claiming the search was unwarranted.

“We’re putting them out the door and telling them to go find a job. It’s a recipe for failure.”

BONNIE TENNERIELLO, A SENIOR ATTORNEY AT PRISONERS’ LEGAL SERVICES

State officials say prisoners who do not qualify to transfer to a lower-security prison are generally moved to a different Souza unit within 18 months of their release. “The unit allows individuals without external distractions to participate in the standard discharge process, focus on individualized reintegration plans, and have access to community transition opportunities,” state officials said in a written statement.

But Vital says he was never given that opportunity. He also unsuccessfully lobbied the state to transfer him to a lower-security prison in 2021. He argued that he was a different man from the troubled teen first locked behind bars. He doesn’t deny his past relationship to gangs, but says his focus now is on taking care of his son and getting a job.

“I am not ashamed of where I came from,’’ he said. “I’m trying to change the direction of even my young homeboys — that you can do positive things. Where you’re from don’t define you.”

Courtesy of Jamual Vital

Just prior to his release, Vital says he was locked into the “Secure Adjustment Unit” — even more restrictive than a regular cell — because of an altercation with other prisoners. Locked in his cell for 21 hours a day, he said the only time he was allowed out was to a cage to exercise or sit, shackled to a table.

The night before his release, Vital says he paced in circles, listening to yelling and recoiling from the stench of feces that wafted from other cells.

That morning, his younger brother met him at the prison gates and took a picture: Vital looked dazed, standing in front of the facility.

A few weeks later, Vital told GBH News he was having trouble thinking clearly. He is now looking for work but says everyday tasks like shopping for diapers at CVS can leave him in sweats.

“I’m just taking it day by day,’’ he said. “That’s all you can do.”

This piece was republished from WBGH.org.