Overtown residents got a shot at homeownership 50 years ago. Now it’s falling apart

By Joshua Ceballos and Daniel Rivero

On May 3, 2024

Lillian Slater has lived in the Town Park Village co-op since the 1970s. More than 50 years after the co-op was built, Slater fears that her longtime home is falling apart.

When Lillian Slater moved into her Overtown apartment in Town Park Village in 1976, she bought into the utopian vision behind the project. One of the few cooperative housing complexes in Florida at the time, the pitch was for Overtown residents to come together and own something for themselves.

“Each one that pays rent here, they has a share. They’s a shareholder. We all in it together,” Slater said of the idea that she and her Miami neighbors believed in upon moving in.

Slater was so invested in the co-op’s mission and its 147 units that she served for decadeson the cooperative board that oversees it. The 84-year-old’s neighbors know her as the person who’s fought for them and for the community.

But now, things are falling apart.

Shareholders own percentages of the nearly 7-acre property right in the middle of the city of Miami. Some have lived in their apartments for decades. Four were evicted by the co-op board on a single day in March. An $18 million grant meant to rehabilitate the crumbling complex has nearly dried up — with little to show for it.

To top it all off, the entire property was recently put up for sale to developers for $38 million, at a time when the people of Overtown face rampant gentrification.

Residents were shocked at the potential sale. Shareholders, they said, were kept in the dark.

“A lot of people that was on the board have passed away, and I was the only one left trying to keep it together all these years,” Slater told WLRN, fighting through tears. “It really hurts me, to my heart, that it’s in this situation.”

The story unfolding in Overtown — one of Miami’s poorest neighborhoods — is a tale of what happens when the hard realities of self-government in a low-income community collide with the pressures of real estate development, while a government bureaucracy tries to fix the problem with money.

Apartments at Town Park Village, which was built in 1970, are in a state of disrepair. Mold covers several walls and surfaces, and layers of paint have long since chipped away.

Residents are struggling to piece together the complicated puzzle, but what they have shared raises serious alarms. One government official involved with the property’s renovation is similarly confused and put off by the situation at the co-op.

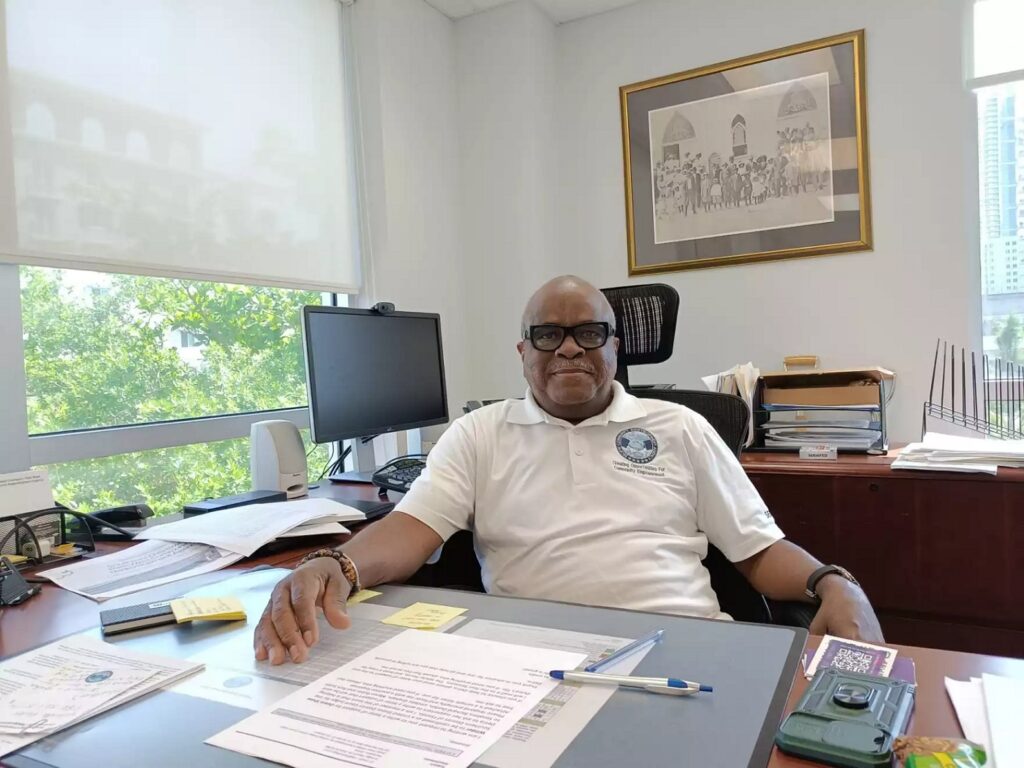

“What’s going on at Town Park Village is horrendous, in my opinion,” James McQueen, the executive director of the Community Redevelopment Agency for Overtown, told WLRN. “We continue to investigate what’s going on there because of the dollars we have invested.”

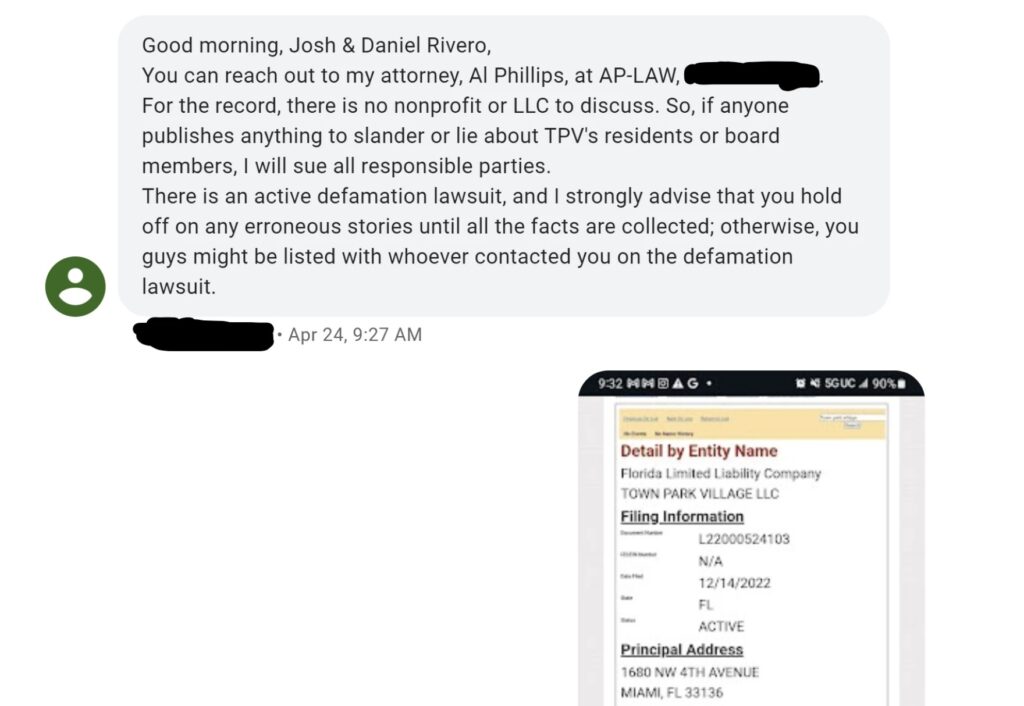

Dana Milson, the president of the cooperative board, would not agree to multiple requests for an interview with WLRN to address widespread confusion in the community or the potential property sale. Nor did she or her attorney respond to questions sent by WLRN via email. In a text message, Milson referred to residents voicing concerns and confusion about the situation as “cowards.”

A text message from Town Park Village President Dana Milson to WLRN reporters.

“The folks complaining or stating they have no clue continue to lie,” she wrote.

The same day WLRN sent questions to Milson and her attorney, a law firm representing Town Park Village sent a cease and desist letter to Bernice Slater, Lillian Slater’s daughter and caretaker. The letter threatened legal action and “further disciplinary action” if Bernice communicated at all about Milson, her associates or Town Park Village.

Bernice said she fears retaliation against her and her mother.

The stakes could not be higher for Town Park Village residents. In a city with one of the worst affordable housing crises in the nation, low-income families at Town Park Village are able to pay less than $700 per month for a four-bedroom apartment.

Town Park Village was founded on the idea that self-governance and ownership is better than renting. The reality of the experiment has been filled with triumphs and pitfalls, with threats of displacement and homelessness always looming over the horizon.

This time feels different, residents say. Distrust and a palpable sense of confusion abound, along with fear and a sense of powerlessness despite the democratic ideals the community was founded upon.

“Where’s our voice? We have no voice around here,” said Tracy Black, who moved into the complex in 1971, at age 7.

“I don’t know what’s going on, but they saying we gotta leave,” she said.

A mural in the Town Park Village cooperative apartment complex in Miami’s historic Overtown.

A radical vision for a shot at ownership

When Town Park Village was first built in 1970, its founders saw it as a chance for low-income Miamians to have something they could only dream of.

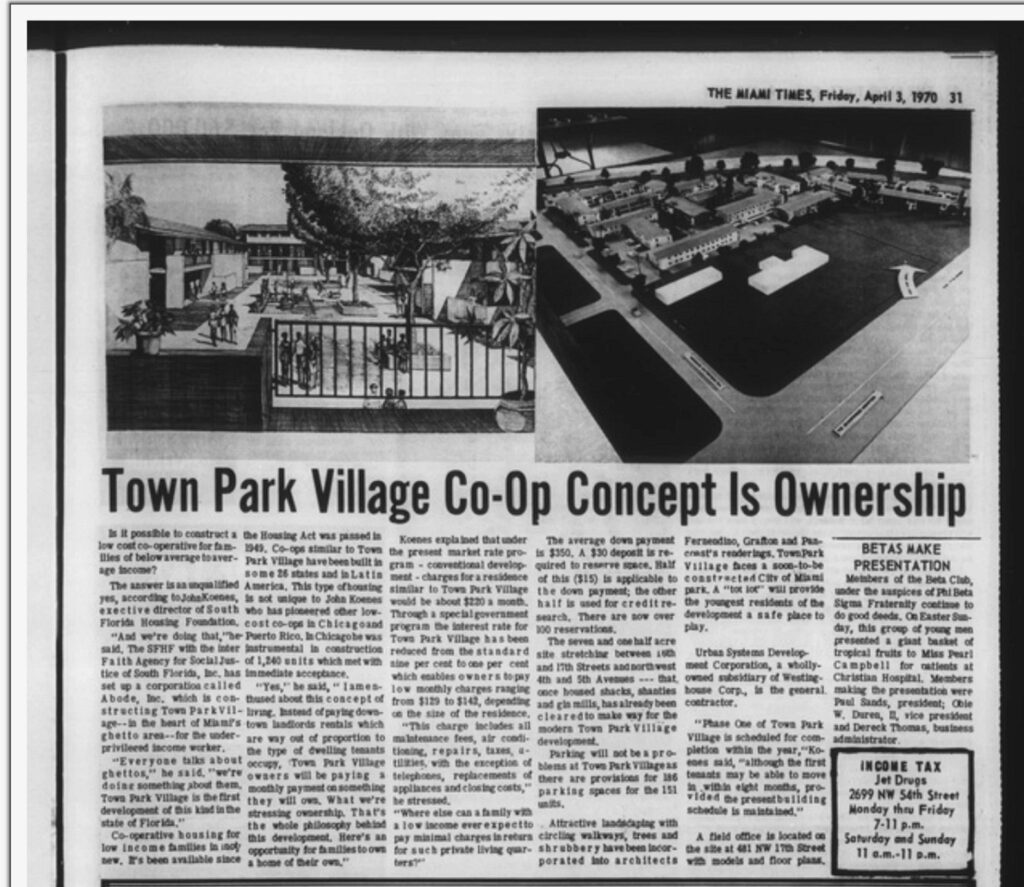

“What we’re stressing [is] ownership. That’s the whole philosophy behind this development. Here’s an opportunity for families to own a home of their own,” John Koenes, then-executive director of the South Florida Housing Foundation told the Miami Times in April of that year.

A newspaper ad placed in 1969 boasted: “Only $350 required to become an owner in the newest concept of homeownership.”

Even 50 years ago, people in Miami were concerned about unaffordable rents in the urban core. Town Park Village was imagined as a cooperative haven where Overtown residents could own their apartments at a reasonable price.

“Instead of paying downtown landlords rentals which are way out of proportion to the type of dwelling tenants occupy, Town Park Village owners will be paying a monthly payment on something they will own,” Koenes told the Miami Times. “Where else can a family with a low income ever expect to pay minimal charges in return for such private living quarters?”

Residents of Town Park Village aren’t renters, they’re shareholders. When they put a down payment on a unit, they’re buying shares in the property. Rather than rent, they pay monthly “carrying charges” which consist of mortgage payments, taxes and maintenance fees. Unlike regular tenants, shareholders are registered with the Miami-Dade County Property Appraiser as owners of their individual units, like a condo.

When the mortgage on a co-op is paid off — like it was at Town Park Village — the shareholders own the property together.

Stressing homeownership for low-income groups — not private rentals or government-funded public housing — was a radical vision of the future of housing that spread throughout the U.S. between the 1950s and 1970s.

Town Park Village No. 1 was among the first projects of its kind in Florida, and hopes were high it could bring systemic change to impoverished areas.

A clip from the April 3, 1970 issue of the Miami Times, Miami’s Black-owned newspaper, announcing the construction of the Town Park Village co-op.

The utopian vision quickly butted heads with reality after residents moved in. The year was 1971.

Koenes told the Miami Herald at the time that while he believed in the vision, people accustomed to renting needed to be “guided in their new experiment of self-governance.”

As a cooperative, the shareholders would have to elect a board of directors among themselves, and that board would be charged with making decisions that would affect the low-income residents, many of whom had been displaced from the construction of Interstate 95 a few years earlier.

To help the residents, Koenes set up a management group to manage the property for the first three years. After that, residents would be on their own. He feared that, without help, residents would struggle to collect payments from their neighbors to repay the $2.6 million federally-backed mortgage loans, at a 7.5% interest rate. Accounting for inflation, that loan would be worth more than $21 million in 2024.

Most of all, Koenes worried the low-income shareholders would struggle to raise funds and manage the property.

His fears were soon realized.

Financial troubles emerge

In 1977, the cooperative defaulted on the mortgage loan, and the federal government had to step in to square things with lenders. Then, it happened again. By 1982, the cooperative owed the federal government $382,000 in missed mortgage payments.

With interest accumulating, more money was owed than the original loan. Some residents owed thousands of dollars in back payments. When the then Reagan administration threatened to foreclose the whole property, evict everyone and sell the development off on the private market, a 1982 shareholder meeting was described as “warlike,” the Miami Herald reported at the time.

Someone shouted from the back of the room in the shareholder meeting: “They’ll get nothing but ashes.” Another resident warned of “riots” if the plan moved forward, saying: “They’ve never had a Vietnam in Miami. They will.”

Miami’s Black community was only two years removed from the 1980 riots that occurred after a jury acquitted white police officers for killing motorist Arthur McDuffie. Seventeen people were killed in the unrest.

Just months after that meeting, another riot erupted in Overtown, just blocks from Town Park Village, after a Latino police officer shot and killed an unarmed 20-year-old Black man at an arcade.

The Reagan administration backed off. Payments restarted, but upkeep problems continued, and the property deteriorated. By 2010, things had gotten so bad that the entire property was at risk of being condemned by Miami-Dade County. A report showed an estimated $7.7 million in repairs was needed to bring the property into compliance.

But that was the year the cooperative hit a major milestone, even if it came 20 years later than planned: the full mortgage was paid off. Shareholders finally owned the property outright.

The mortgage on the property was insured by the Federal Housing Administration. According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the shareholders paid off the loan in 2010, 40 years after Town Park Village was built.

With the loan paid off, HUD no longer had any oversight on the property, aside from 30 Section 8 units, and the federal government could not put restrictions on the co-op to require low-income housing. Section 8 is a federal program that provides money to low-income families to rent an apartment or house.

All the shareholders and residents had to do was figure out how to get money to pay for the repairs.

Letters and sensitive mail have to be stuffed behind a sign at Town Park Village because residents’ mailboxes have been broken and don’t close. Residents say the mailboxes have been broken for some time.

$18 million almost gone

Community Redevelopment Agencies, or CRAs, are used by governments nationwide to revitalize poor or blighted areas of a city with taxpayer dollars.

After nearly a decade of discussions, in 2019, the Southeast Overtown Community Redevelopment Agency — a City of Miami agency headed by the city commission — allocated $18 million in an effort to rehabilitate Town Park Village and keep it in the good graces of the federal government.

HUD had inspected the property and found it had “physical deficiencies” that did not meet federal standards. If nothing was fixed, 30 families at the property that receive Section 8 housing subsidies would have to be cut off, potentially rendering the families homeless.

Structures throughout the apartment complex are in various states of disrepair. Mold climbs up concrete staircases and walls, and mailboxes for co-op residents are broken open. Letters are stuffed behind a sign above mailboxes whose latches won’t close.

Even though the mortgage was fully paid off, the federal government maintained a foothold in the property, and the threat of pulling funding pushed the city to act.

In order to rehab all the housing units, hundreds of residents would first have to be temporarily relocated, building by building, until work was completed. The $18 million was meant to fund the renovation of 12 of 19 buildings — 86 living units.

Two years after the spending was approved, major work finally began on rehabilitating the first batch of units at Town Park Village, according to an annual report. Some residents had already been displaced for two years by this point, and the costs were overrunning before work even started. The Community Redevelopment Agencystaff warned additional money would have to be spent for future phases of the project.

According to public records reviewed by WLRN, the city-selected contractor, H.A. Contracting, has already exhausted much of the funding for the project without being close to finished. As of this March, the contractor billed the CRA for close to $14.4 million to complete only the first phase of renovations — just 46 units. That’s less than one-third of the total units at Town Park Village, and about half of what the $18 million was supposed to accomplish.

The original agreement with the contractor was that all the work on the first two phases of the project was expected to be complete for a total of $18 million, including the cost of relocating residents.

WLRN reached out to Miami City Commissioner Christine King, whose district includes Overtown. She is also chairwoman of the Southeast Overtown/Park West CRA. King referred all questions to the CRA’s executive director.

James McQueen, executive director of the Southeast Overtown/Park West CRA. Pictured here in April of 2024.

James McQueen, the current executive director of the CRA since 2021, said project costs were blown out of proportion from the CRA’s initial estimate for one major reason: the pandemic.

“When we assigned the number to that project, that was pre-COVID,” McQueen told WLRN. “When they set this program up [in 2019], they were operating with the idea that you could have a one-bedroom apartment for $800, $900 … It’s $1,600 now.”

Relocation costs for three years of renovation ate up a huge chunk of the CRA’s grant, as well as increased materials costs for construction after the onset of COVID-19.

The agency ended up spending more than $300,000 per unit from 2020 to 2024, according to records reviewed by WLRN.

When the work on the first phase is done later this year, the CRA won’t be funding any more construction at Town Park Village, because, McQueen said, the property was put up for sale without the agency’s knowledge.

Alongside renovations, evictions

The purpose of the $18 million grant was to keep Overtown’s residents in place and bolster the City of Miami’s stock of affordable housing. The CRA lauded the project as one of its efforts to create or maintain 4,099 affordable housing units in the city.

Miami Homes For All, a local housing advocacy group, estimates Miami-Dade County needs more than 90,000 housing units for households earning $75,000 a year or less to meet demand.

But while the renovations went on, some of the residents who were living in Town Park Village, and some who were relocated, were forced out.

In a single meeting last December, the board of Town Park Village took possession of the shares for 38 low-income housing units, putting the apartments in the corporation’s name. In documents published in property transaction records, the board said the previous shareholders had “abandoned” the properties.

One of the recently renovated buildings at Town Park Village. The Community Redevelopment Agency for Overtown has so far spent more than $14 million on the rehabilitation of the apartment complex.

Lillian Slater, a resident and board member, said she was left in the dark about the decision to strip shares away from longtime residents and families. As a board member, she should have known. Town Park Village’s by-laws require that board members be given at least three days notice of any board meetings unless they waive their right to notification.

“Nobody said a word to me about anything,” she said. “Not at all, baby.”

The other members of the Town Park Village board did not respond to WLRN’s requests for comment.

On top of shareholders losing their shares, the cooperative has been filing a spate of evictions, including against shareholders.

Carolyn Patten had an agreement that she would leave her apartment in March 2021 and that she’d return when renovations were complete. In the meantime, she continued to pay her monthly $646 to the cooperative. This past March, the board moved to evict her from her unit — but she was already locked out.

According to court filings from the eviction case, Patten was not allowed back into her apartment when renovation work was complete last year, so she just left.

“When defendant [Patten] tried to get possession/access to the unit in 2023, plaintiff [Town Park Village No. 1, Inc.] was non-responsive. As a result, defendant stopped paying rent April 2023 and has no rental obligation to plaintiff,” Patten wrote in a court filing.

Other relocated residents were allowed back, but found that while they were gone, their monthly payments — which they refer to as “rent” though they are, strictly speaking, carrying costs — have gone up. They also faced an imminent potential property sale that many of them knew nothing about.

A Town Park Village shareholder who asked not to use their name for fear of retaliation from the co-op board told WLRN they were out of their unit for three years. When they tried to move back in, they were told that the monthly payments had gone up because the unit was renovated.

Payments went up by $150 per person in the household to cover water and maintenance, they were told. Their monthly costs for the unit doubled from around $700 to $1,400.

While they can afford that rent for now, the resident said if it went up any higher they’d have to pack up and leave.

“I’m really feeling like we don’t really stand a chance. How can we beat gentrification and people working behind the scenes against us?” they told WLRN. “That’s the state of the world we live in. Everyone’s a paycheck away from being homeless.”

Brian Zeltsman, director of architecture and development for the Overtown CRA, said the agency heard that relocated shareholders were being charged more rent but cannot do anything about that because the board has ultimate control over the co-op.

“Obviously that’s an issue that we’re not in support of. I don’t know how that came about,” Zeltsman told WLRN.

Entire property listed for sale

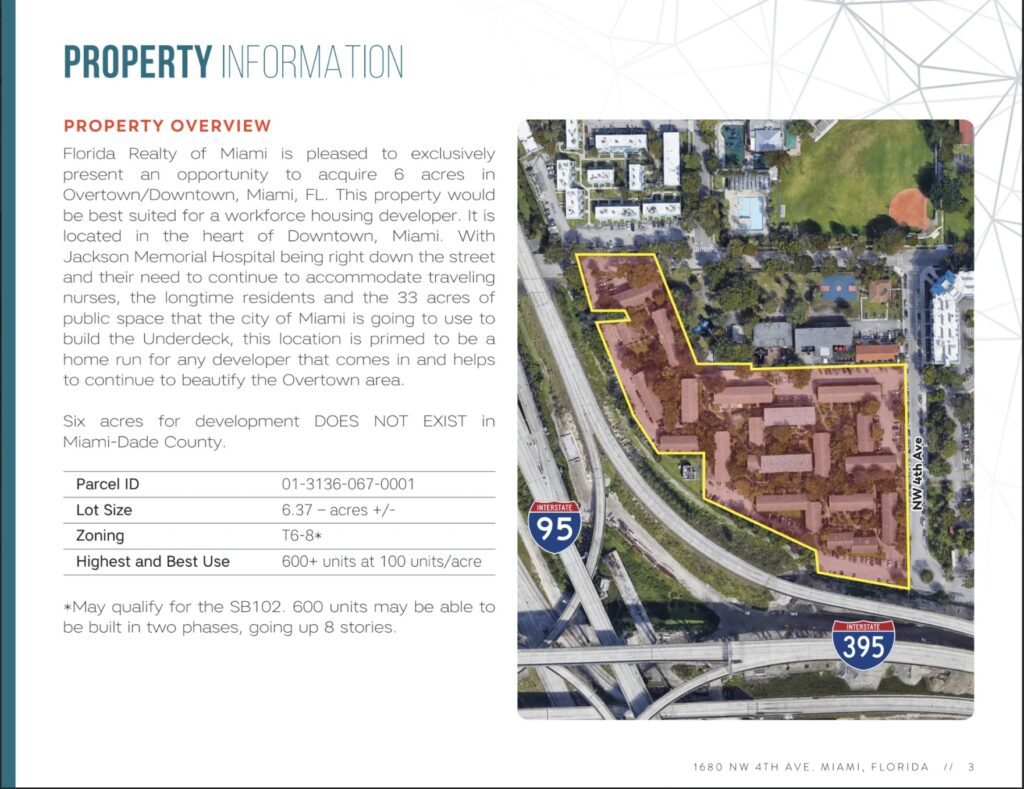

Last November, the entire property of the Town Park Village cooperative housing community — spanning nearly seven acres in Overtown — was listed for sale online for $38 million.

Nellie Spann has been in Overtown since 1971. Her unit is owned by the estate of her husband, Freddie, who died in 2019. She told WLRN that the co-op board has left residents out of the loop. She wouldn’t have known her longtime home was up for sale if not for word of mouth.

“They don’t tell you that much or nothing. They didn’t even tell [us] it was on sale. But if you looked it up online, we saw it online,” Spann said.

A PowerPoint presentation for the sale prepared by Florida Realty of Miami advertises the Town Park Village property as an ideal opportunity for a workforce housing developer in “the heart of Downtown, Miami.” Up to 600 units can be developed on the site, according to the presentation.

The listing agent for the property declined to comment for this story.

As recently as Wednesday, May 1, the property was listed on the real estate website Loopnet.com. As of the afternoon of May 2, the property no longer appears listed.

“This location is primed to be a home run for any developer that comes in and helps to continue to beautify the Overtown area. Six acres for development DOES NOT EXIST in Miami-Dade County,” the presentation states.

Residents told WLRN they weren’t consulted about the sale, despite most of them being partial owners of the property. When they brought up the listing at a board meeting, residents said board leadership told them that the sale would go through and they would have to find somewhere else to live.

Even the Southeast Overtown/Park West CRA, which had committed $18 million to preserving Town Park Village for its residents, learned of the sale by chance.

“Through no conversation with the board of Town Park Village, it came to our attention that the place was for sale. We weren’t noticed that it was for sale, it was just that someone looked in the real estate section and saw that,” McQueen told WLRN in April. “My first reaction was, ‘How could that be without them [giving us notice?]’ But they did not.”

McQueen said the CRA put in an offer to the co-op board to buy the property, to maintain it as an affordable housing option for Overtown. Though the board president expressed initial interest, he said, she ultimately told the CRA that they had another buyer lined up.

Since the board is selling the property to a developer and seemingly not trying to keep the affordability for the residents, McQueen said he’s instructed the CRA to finish funding the first phase of repairs but stop all work after that. He won’t continue to bankroll a project with taxpayer dollars if it’s just going to be sold and redeveloped.

“I don’t think it’s fair for the CRA to take money that could be used to improve other housing in the area that’s in desperate need of improving when some private developer could come and not make any of the properties affordable,” he said.

If the property is ultimately sold, McQueen said the millions of dollars the CRA has already invested must be paid back to them — millions of dollars that could have gone to other affordable housing projects over the last five years.

A map of Town Park Village with an accompanying pitch explaining why it is ideal for sale, according to realtors putting the property on the market.

In a real sense, McQueen feels regretful that things are turning out this way. Residents beg him for answers, for some capacity to shed light, to make sense of whatever is happening. But he is not an investigator. His agency controls the money, but the project was greenlit before he came on board. Now the whole thing is a mess.

Maybe more of a mess than if the CRA never got involved at all.

“If the CRA had not gone in and tried to improve, none of this would have ever come up,” said McQueen. “The people’s condition would have been their condition. They’d have stayed in those units. They’d have been dealing with this board. When stuff broke down in their various units, they would have had to find a way to fix it.”

A void in communication

Residents say the cooperative board has signaled that the money is all spent, and that they should not expect more rehabilitations to be done.

But the cooperative board has been elusive and difficult to communicate with, residents said. Monthly payments must now be slipped into a crack on an office door, several residents told WLRN. The previous property management company used to staff the office. Phone calls, texts and emails are no longer answered, residents told WLRN. In the void of communication, and as the property was listed for sale at $38 million, many feel betrayed.

“Yeah, now we just have to put it in a drop box,” Tracy Black, a longtime Town Park Village resident, told WLRN.

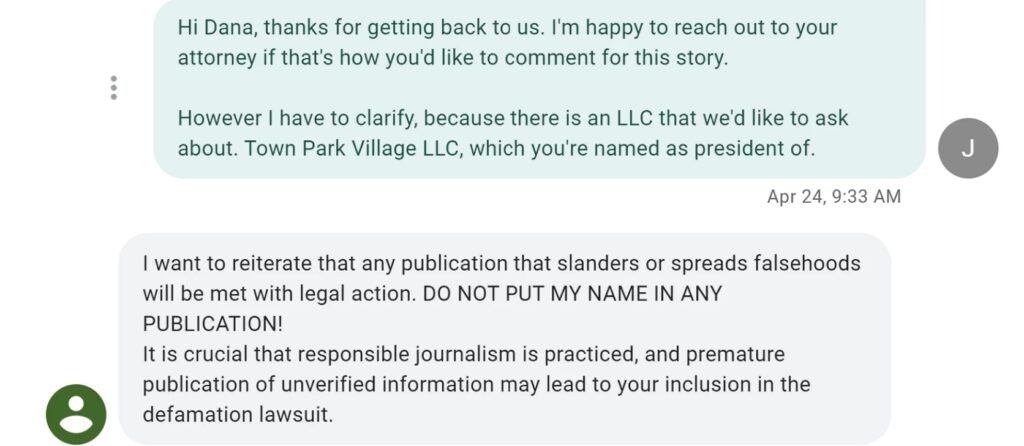

In part the skepticism comes from the fact that in 2022, two cooperative board members helped start a new company with a familiar name: Town Park Village LLC. The new company lists the same address and phone number as the original board. The president of the new company is Dana Milson, who also serves as the president of the cooperative board.

In a series of text messages, Milson wouldn’t answer questions about Town Park Village LLC. When WLRN showed her a screenshot of a corporate filing with herself listed as President, she responded with a threat of legal action.

In a text message to WLRN, Milson declined to talk about an LLC with a nearly identical name to the co-op board. Residents are unclear on what the LLC does. Milson is president of both the board and the LLC.

A text exchange between WLRN and Town Park Village president Dana Milson

It’s unclear who exactly is in charge of the co-op, and what management company is responsible for running the day-to-day operations.

Milson and her attorney did not respond to any questions asked by WLRN.

Residents are told to make their checks or money orders out to “Town Park Village” and leave them in an open slot at the management office, which has no one in it for most of the week.

McQueen, the CRA director, said it’s been a challenge to figure out who is in charge to communicate about the rehabilitation and the sale.

“With a co-op, it becomes very difficult to find out who’s the ownership, and it becomes even more difficult … to find out who’s in charge on a daily basis,” McQueen told WLRN.

Plea for help

Bernice Slater lives in Town Park Village with her mom, Lillian, who has been a leader in the community since the 1970s.

The people of Town Park Village are longtime Overtown residents, many of whom are low income and have few options for where to live as Miami becomes increasingly unaffordable.

More than anything, they’re looking for someone to help.

Slater, the longtime co-op board member, has reached out to numerous local and state agencies to find a solution to the crisis she and her neighbors find themselves in.

Slater wrote to Florida’s Division of Corporations raising concerns about what she called a “fraud” taking place in her community.

She’s also written to the Florida Attorney General’s Office, the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office, the City of Miami Police Department, and sent certified letters to the Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation, the agency that is supposed to regulate condominium boards and cooperatives.

“We emailed everybody. State Attorney’s Office, even the feds. The housing people, everybody we could get to. And still, nobody’s come forward to help us,” Slater told WLRN. “Somebody needs to help us.”

This piece was republished from WLRN.