Paid or unpaid, child care is vital to the economy. This program recognizes that

Andrea Hsu/NPR

A half dozen women — in their 30s, 40s and 50s — gather in a classroom in Phoenix for a few hours on a weekday morning.

They are all caregivers of young children.

There’s Yosbri Rojas. When her own 8-year-old is at school, she takes care of two younger children, whose father works with Rojas’ husband installing fiber optic lines.

“I like that the children feel happy with me,” Rojas says in Spanish.

Graciela Cruz is also here. She works early mornings in a warehouse, from 4 to 9 a.m. During the day, she parents her own 2-year-old daughter and also watches her neighbors’ 1-year-old while the child’s parents are at work cleaning houses and offices.

Cruz and Rojas are participants in an Arizona state-funded initiative called Kith and Kin. The 12-week program aims to give family, friend and neighbor caregivers the kind of training and support that licensed caregivers are required to have.

Licensed or not, caregivers make work possible

While most federal and state funding for child care in the U.S. goes to licensed settings, Arizona is one of a number of states that have long recognized the importance of informal caregiving arrangements that are allowing millions of parents go to work.

Such arrangements, which can be paid or unpaid, are especially common in immigrant communities and communities of color, where many parents hold jobs with nontraditional hours and prefer caregivers who share their language and culture.

Andrea Hsu/NPR

A study in the south Phoenix area found that 60% of children from birth to 5 years old were being cared for outside of licensed child care settings.

That study led the nonprofit organization Candelen to launch Kith and Kin in 1999.

“There was the high need to provide both training and support” in communities where families with young children live, says program director Angela Tapia.

Now, 25 years later, programs like Kith and Kin are getting renewed attention in the wake of the pandemic, which put a spotlight on the fragile state of the child care industry.

There’s increased urgency from federal and state policymakers and businesses to ensure communities have access to affordable, high-quality child care, paving the way for parents — especially women — to work, an essential element of a robust and well-functioning economy.

A crash course in caregiving fundamentals

The aunts and grandmothers and neighbors who attend the Kith and Kin classes often don’t think of themselves as caregivers, says Tapia, much less as contributing to the economy.

“It’s more something they do out of love and to help their family and friends,” she says.

But caregiving requires more than love, and that’s where the program come in.

Over 12 weeks, the caregivers, who are predominantly women (though they do see the occasional grandfather or uncle) undergo training in basic health and safety, including CPR, as well as more advanced topics such as child development, positive discipline and injury prevention.

The women share personal challenges, ask for advice and offer comfort and support.

Funding comes from Arizona’s tobacco tax

The sessions are paid for in part by Arizona’s tobacco tax. Candelen estimates it trains about 1,000 caregivers a year.

Melinda Gulick, CEO of Arizona’s early childhood agency First Things First, says the funding is recognition that all children, regardless of where they spend their first years, deserve a high quality early childhood experience.

“Being ready on the first day of Kindergarten is the biggest indicator of academic success and success in life as well,” she says.

Gulick points out, in some rural parts of Arizona, there is no licensed child care, and even where there are options, Arizonans are known for wanting choice.

“This is a liberty and freedom state,” she says. “For many parents, the best place for [children] to be is with their auntie or their grandmother or in a co-op in their neighborhood.”

Andrea Hsu/NPR

Keeping caregiving in the family

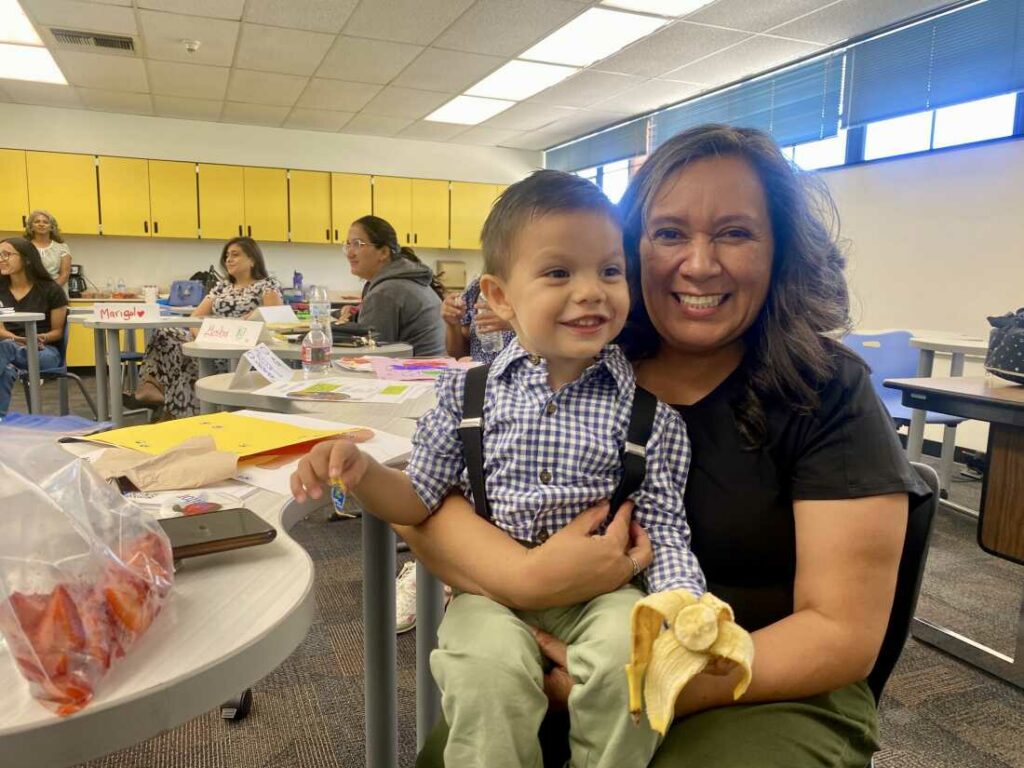

That’s certainly how Cynthia Diarte felt when she had her son Esteban. He’s now two and a big fan of Bluey, the beloved children’s television character.

Diarte, a teacher, grew up on the Texas-Mexico border, cared for by her grandmother while her mother went to work at an airport restaurant.

Diarte says it was never a question who would watch her children when she became a mother herself. Her mother, Elvia Elena Nunez, insisted she be the one, carrying on their family tradition.

As a Kith and Kin participant, Nunez has appreciated learning new ways to keep Esteban entertained without screens. She also cherishes the community she’s built with the other caregivers and the enrichment Esteban has gotten through the program.

While class is in session, Esteban is with other toddlers, singing songs and playing games in the child care room down the hall.

“He’s bringing more vocabulary. He’s starting to speak up a little bit more,” says Diarte. “He really needed that social aspect, the relationship with other kids.”

And she expects those relationships to endure. A side benefit of the Kith and Kin classes is how close the caregivers become.

“They end up becoming like the madrinas, like the godmothers, the godparents, to each other’s children,” says program director Tapia. “They stay connected throughout the years.”