Tarrant County residents of color work to shatter stigma associated with mental health struggles

By Dang Le

On September 6, 2023

Fort Worth resident Christopher Blake never considered sharing the trauma from his military service when police profiled him two decades ago.

Then, three years ago, he started therapy.

Blake, a 39-year-old Black man, had the “tough-it-out” mindset. For many communities of color, the sense is that such a mindset, not unusual in mental health discussions, has contributed to higher rates of suicides. The psyche is so deeply ingrained in some people of color that even among those who have embraced conversations about mental health, barriers to actually seeking care still exist.

“It’s a pride thing — why you don’t want to admit that you may have some kind of mental health issues,” he said.

Blake turned to therapy after developing suicidal thoughts, he said. He became aggressive and confrontational, and he would get triggered if someone raised their voice at him, or if he saw a weapon that wasn’t in his possession.

He calls himself a “short-ticking time bomb” — he always watches his surroundings, and he makes up negative scenarios in his mind even though nothing is wrong.

“As I’ve gotten older, it has gotten worse,” he said.

Lower reporting rate, higher suicide percentage

In 2020, people of color were generally less likely to report experiencing any mental illness or substance use disorders compared to their white peers.

Just over 28% of Black adults and 27% of Hispanic adults reported having a mental illness or substance use disorder in 2020, compared to 36% of white adults, according to Kaiser Family Foundation, a health policy research nonprofit.

However, the nonprofit found that a lack of culturally sensitive screening tools to detect mental illness along with structural barriers — including racism and socioeconomic disparities — may contribute to the underdiagnosis of mental illness among people of color.

The death rate by suicide also rose faster among people of color between 2010 and 2020 compared to their white counterparts.

‘I feel like I should be OK to get through everything’

Chris and Martha Thomas understand the pain of losing someone to suicide.

Their daughter, Ella, died by suicide in 2018. The Thomas family had heard about some microaggression toward their daughter, who was biracial, but they said they genuinely didn’t know the depth of their daughter’s pain.

Following Ella’s death, the Thomases co-founded The Defensive Line along with their son, NFL player and Coppell High School graduate Solomon Thomas. The organization serves everybody but focuses on the needs of young people of color. This summer, the family spoke at TCU about raising awareness of mental health issues for minorities.

“A lot of times, people feel like, ‘Because our ancestors have been through so much, I feel like I am embarrassed about the fact that I’ve gotta talk about my mental health. I have people go through Jim Crow or slavery or discrimination, I feel like I should be OK to get through everything,’” Chris Thomas said.

Challenges for minorities in addressing mental health

While research has shown that minority groups aren’t more likely to have mental health challenges than the population at large, they are less likely to seek or receive services from a mental health organization, said Brian Villegas, senior director of Adult Behavioral Health services at My Health My Resources of Tarrant County.

Many reasons are cited for this, from limited availability of services in local communities, mistrust of the health care system and language barriers that affect minority communities in getting help, Villegas said.

“I’ve noticed in my encounters with patients that they feel discriminated (against) at times and that they don’t have the same right to access the resources that we all have available to us,” he said.

The stigma around mental health discussions

As an Indian immigrant, TCU student Rini Cherian has witnessed many people in her community having a crisis, but that they wouldn’t go to counseling. They’d just brush the matter off because they don’t know of anyone to talk to, she said.

Cherian didn’t have access to mental health resources until college, despite a history of abuse and adverse childhood events she experienced as an immigrant, she said.

Cherian is studying to become a psychiatric nurse practitioner. She left out the psychiatric part when she told her parents about her choice, she said.

“We do have a lot of cultural barriers because a lot of our parents don’t believe in getting help,” she said. “It’s like, ‘Oh, that’s not real.’”

Vorice Perryman, director of Youth Intensive Services at MHMR of Tarrant County, said his job involves working with young people and educating their parents. Numerous times, his young patients told him that the people in their lives didn’t understand how they felt.

The key component is “being able to provide,” Perryman said. His team works to educate and involve all of those in the family dynamic to help them better address mental health challenges common among their young people.

Minority mental health care disparities

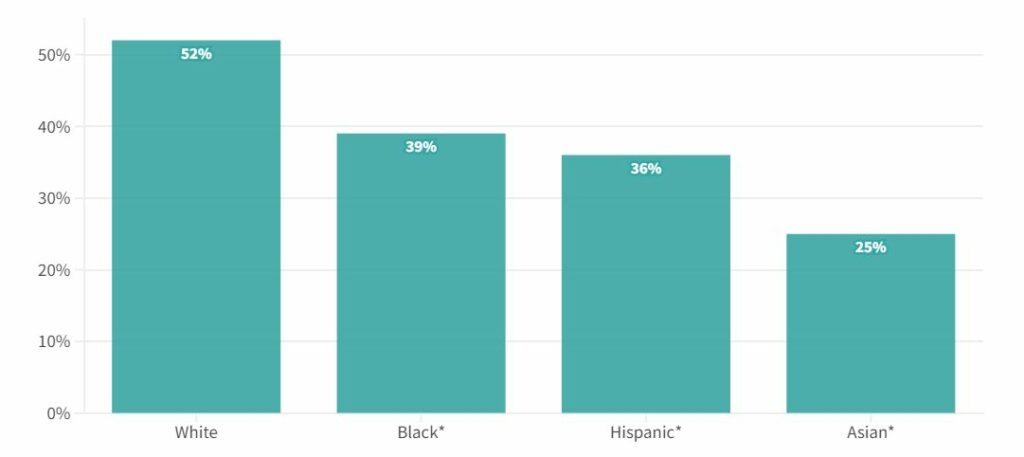

The Kaiser Family Foundation found that Black, Hispanic and Asian adults were less likely to receive mental health services than their white counterparts.

“It’s important to talk about the topic because there’s so many barriers to mental health care. So yes, talking about suicide, talking about anything mental health related — it’s so important,” Cherian said.

Black, Hispanic and Asian adults were less likely to receive mental health care than their white counterparts in 2021

While over half (52%) of white adults reported receiving mental health services in 2021, only 39% of Black adults, just over a third of Hispanics (36%) and about a quarter (25%) of Asians did, according to Kaiser Family Foundation.

Some people would believe that their mental health problems would eventually go away and that they would feel better once their lives stabilized, Villegas said.

The opposite is true.

“They keep getting into other challenges that keep compiling and compiling: anxiety, depression, post or post-traumatic stress disorder, so it augments,” he said.

MHMR of Tarrant County welcomes those who believe they’re isolated or discriminated against and mistrust the system, Villegas said. The center has focused on building a diverse staff and professionals at the clinics while listening to the focus groups in the community.

Chris Thomas of The Defensive Line has his own story as a Black man. He said he never talked about mental health, but he has realized that it doesn’t affect any specific demographic.

“It impacts everybody — socio-economics, demographics, race, gender, so we’ve got to find a way to talk about it so people know that it’s an issue and that it can be addressed,” he said.

This piece was republished from the Forth Worth Report.