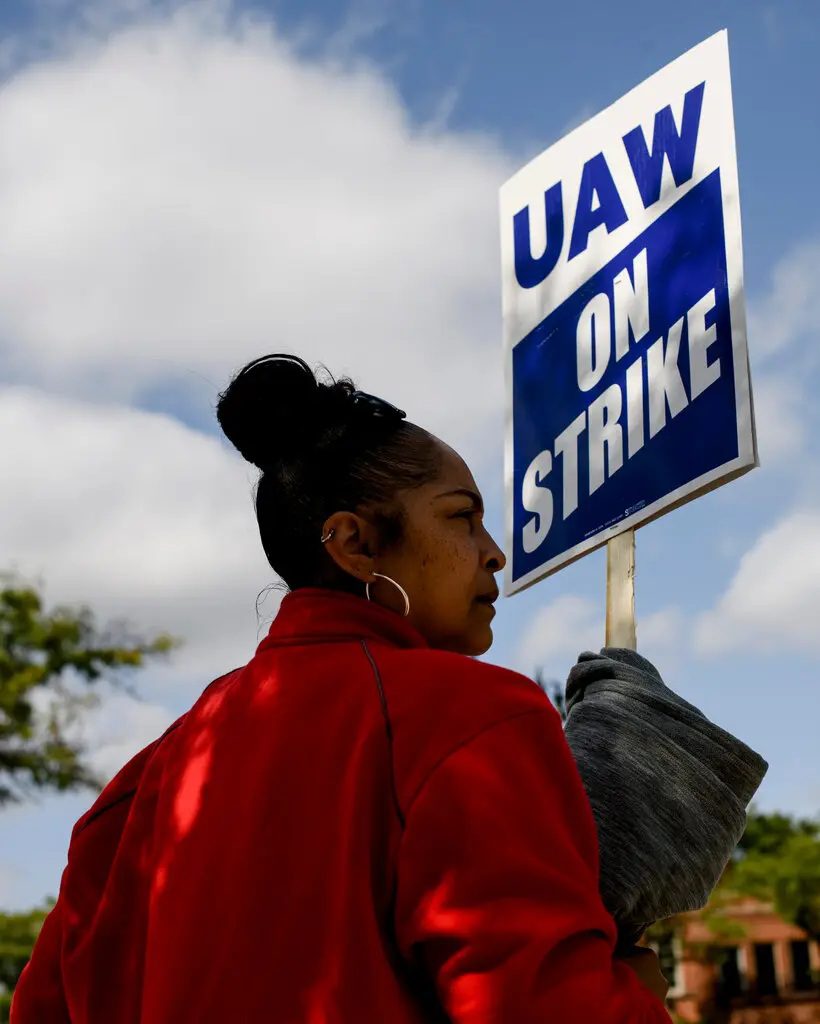

The Autoworkers Go on Strike

The action by the United Auto Workers is part of a burst of labor activism attempting to reverse a decades-long trend.

By David Leonhardt

On September 15, 2023

Tumultuous labor strikes are a natural part of an economy with an expanding middle class.

I realize that idea may sound surprising. Strikes are unpleasant, after all. They disrupt life for a company’s workers, managers and customers. (Here is the latest Times coverage of the United Auto Workers strike that began this morning.)

It’s usually better for everyone when a company’s executives and union leaders can agree on a contract without a walkout. But history shows that the potential for a strike, and sometimes the reality of one, is necessary for workers to receive healthy raises and ensure good working conditions.

The decades after World War II are rightly remembered as a time when the American middle class was expanding rapidly. Median family income more than doubled over a 25-year period starting in the 1940s, even after taking inflation into account. The income gap between rich and poor families shrank, as did the gap between white and Black families.

These were also years when strikes were a regular feature of American life. In the 12 months after World War II ended, almost five million Americans, or roughly 10 percent of the work force, went on strike, including autoworkers, film crews in Hollywood, steel workers, coal miners and meatpackers. During the 1950s — a supposedly conformist decade — more than 1.5 million workers went on strike every year on average.

The strikes helped create the American middle class. Without at least the possibility of a disruptive strike, companies are often able to keep wages relatively low. They can bet that workers won’t quit for higher-paying jobs elsewhere. This bet often pays off, particularly when industries are highly concentrated with only a few large companies.

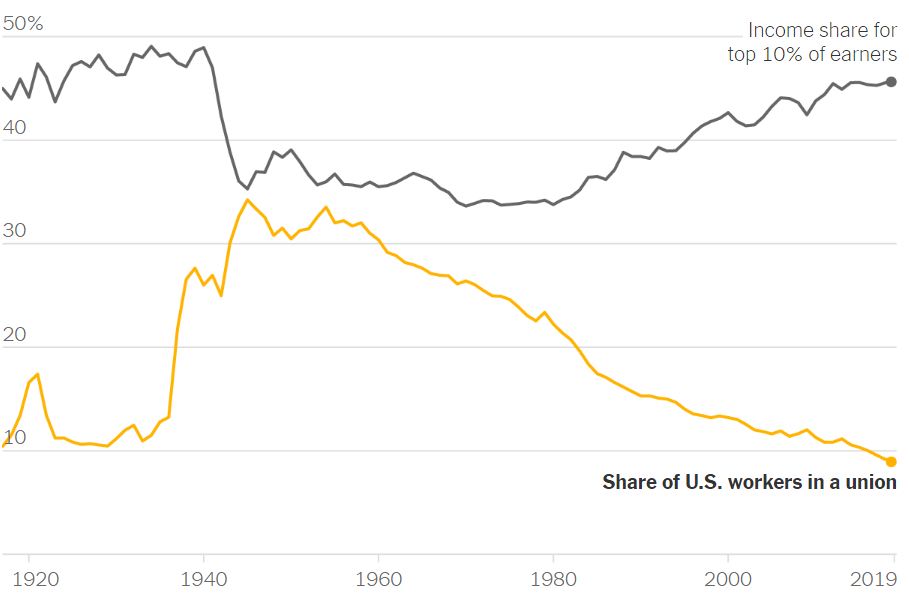

That’s essentially what has happened over the past few decades as unions have withered and companies have consolidated. The economic trends have been the opposite of what they were in the mid-20th century: Executive pay and corporate profits have grown faster than the American economy — and much faster than wages for rank-and-file workers.

Union participation and income inequality

By The New York Times

Makeup pay

The current burst of labor activism, in the auto industry, Hollywood, Amazon warehouses, Starbucks stores and elsewhere, is an attempt to reverse these trends. The United Auto Workers, for example, agreed to large pay cuts for new workers when the industry was near collapse during the financial crisis almost 15 years ago. Since then, Detroit’s Big Three — General Motors, Ford and Chrysler (now owned by Stellantis, a Netherlands-based company) — have recovered, earning large profits, but worker pay has not rebounded so well.

Union leaders are now asking for a 36 percent wage increase over four years, to match the similar recent pay increase for top executives. The union also wants pay to rise automatically with inflation in the future, as it did before the financial crisis. Without such cost-of-living increases, inflation causes de facto pay declines every year.

I want to emphasize that the broader importance of unions doesn’t mean that all their demands are reasonable. Sometimes, unions really do make self-defeating demands. The auto industry is a case study. As Japanese and German companies won over American customers in the 1970s and 1980s, Detroit’s unions (along with the industry’s top executives) were slow to recognize the threat and continued insisting on wages and work rules that contributed to the Big Three’s decline.

A classic example was known in the auto industry as a jobs bank — places where workers who no longer had jobs came every day to do little and still be paid. (My colleague Neal Boudette nicely traced this history on an episode of “The Daily” this week.)

In the current negotiation, the U.A.W. is asking for a new version of jobs banks. The updated version would continue paying some employees who had lost their jobs during the transition to electric vehicles, which require fewer workers than gas-powered vehicles.

Is that a sensible demand? I’m not sure. It might be good for individuals, but it could also prevent the car companies from staying competitive with foreign rivals. Likewise, is a 36 percent pay increase a fair catch-up after the previous pay concessions — or is it more than the companies can sustain and instead a sign that neither C.E.O.s nor workers should be getting such big raises?

These are legitimate questions, and I hope that Detroit’s executives and union leaders will hash them out in public. Just keep in mind that if they weren’t arguing over them, the workers would probably be worse off.

This piece was republished from The New York Times.