The Racial Wealth Gap in New York

By Office of the New York City Comptroller

On December 6, 2023

Introduction

Earlier this year, both the New York State Senate and the State Assembly passed bills to establish a state-level commission on reparations. The commission would be charged to examine the legacy of slavery and subsequent racial and economic discrimination against African Americans in New York and to make recommendations for potential remedies and reparations.

The bill is part of a wave of efforts around the country to confront the lasting impact of institutional racism on Black families’ ability to achieve economic security and build wealth. In 2021, Evanston, Illinois became the first jurisdiction in the nation to pass a reparations law. To date, the city has disbursed over $1 million in reparations funds to Black residents impacted by the city’s history of racial discrimination. In California, a Task Force to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans has released its final report to the state legislature and the public. Other efforts to study reparations emerged in cities like Detroit, Michigan; Amherst, Massachusetts; and St. Paul, Minnesota.

Reparations are one part of an attempt to reckon with our country’s centuries-old legacy of slavery and institutional racism. “Virtually every institution with some degree of history in America, be it public, be it private, has a history of extracting wealth and resources out of the African American community,” says author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates. This history is well-documented, particularly in the realms of housing, education, employment, and access to the financial system.

New York State and New York City are no exceptions. From redlining to school segregation, from public health inequity to discriminatory policing and judicial practices, the city and state have both seen their share of de facto and de jure practices that helped white families build wealth while preventing Black families from doing the same.

At the request of State Senator James Sanders, lead sponsor of the reparations bill in the New York State Senate, this brief examines the form and scale of the racial wealth gap in New York (to our knowledge, it is the first effort to do so). For statewide racial wealth disparities, we analyzed data from the 2021 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), a longitudinal survey administered by the U.S. Census Bureau which provides comprehensive information on individuals’ financial well-being and participation in government assistance programs. For New York City, we analyzed data from the 2017-2021 five-year American Community Survey (ACS), for which the range of available information on wealth is more limited.[1]

Our findings, presented below, show stark racial wealth disparities in both New York State and City. We then consider the framework for a “solidarity dividend,” the benefits that New York would see from narrowing gaps of systemic racism.

Racial wealth inequality in New York State

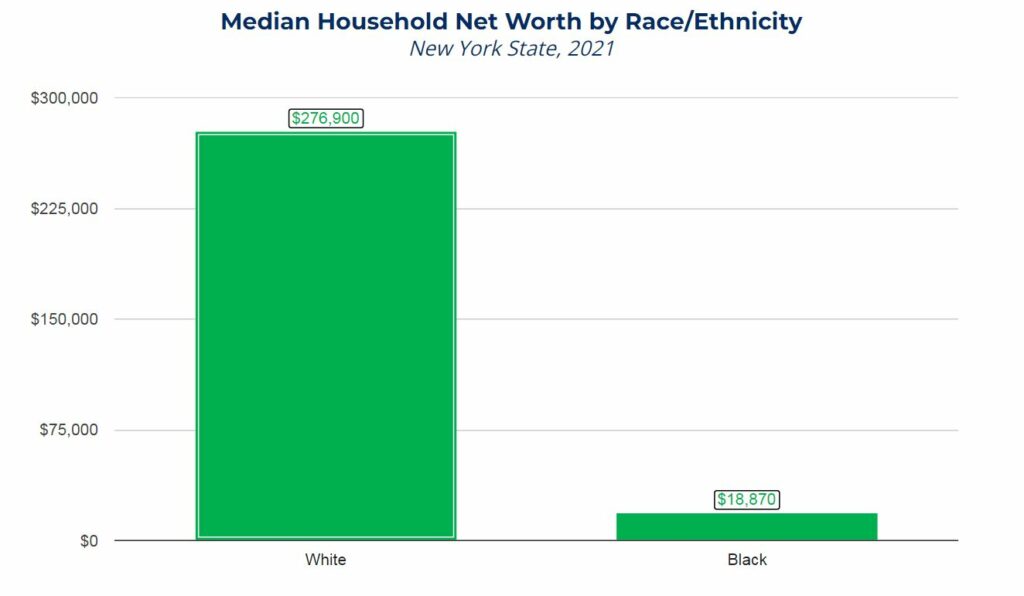

Chart 1 compares the median household net worth of white versus Black New York State residents. For white New Yorkers, this figure is $276,900, which is nearly 15 times (or 1400 percent) greater than the median household net worth of Black New Yorkers of $18,870. Notably, New York State has a wider racial wealth gap than in the United States as a whole, where the median white household net worth is $291,250 and the median Black household net worth is $31,370—a ratio of 9.3.

Chart 1

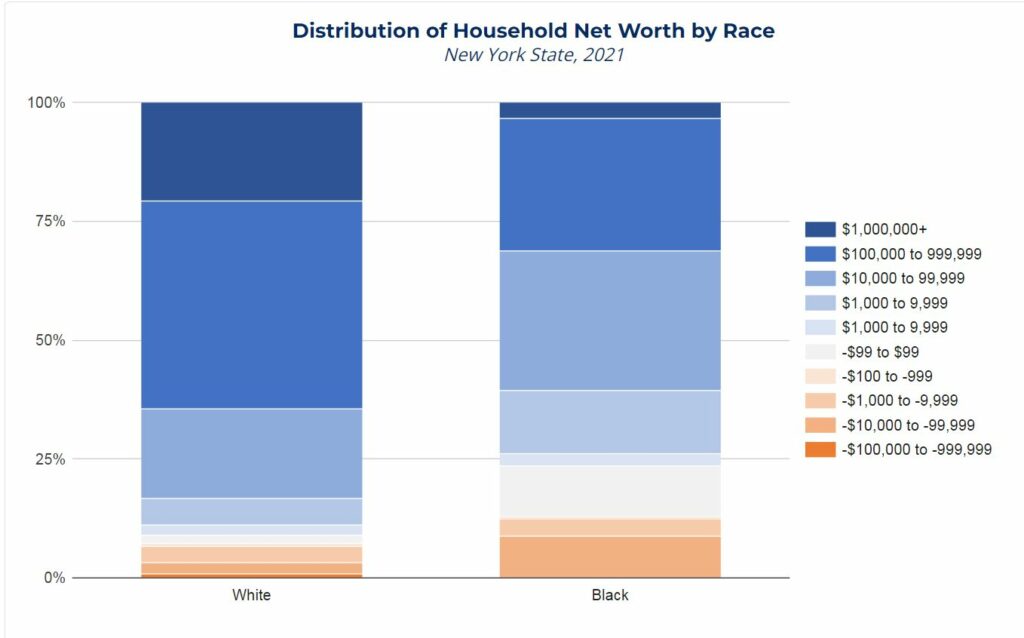

Chart 2 provides more detail on the full distribution of household net worth among white versus Black New York state residents. While 21 percent of white individuals live in a household with a net worth of $1 million or above, only less than 4 percent of Black individuals do. Meanwhile, 13 percent of Black New Yorkers have a negative household net worth—meaning they owe more in debt than the value of all their assets—compared with 7 percent of white New Yorkers.

Chart 2

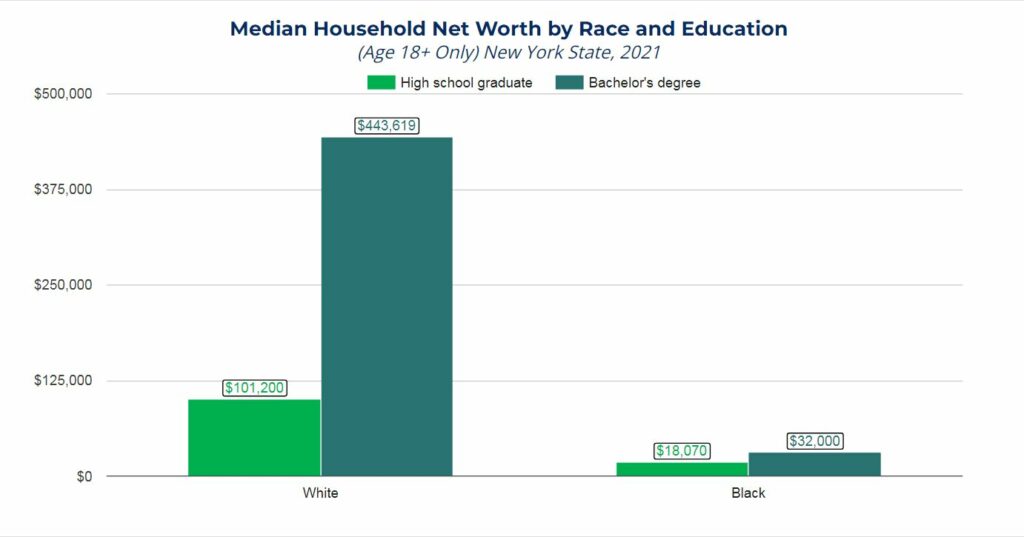

Chart 3 reveals that differential educational attainment between white and Black New York State residents does not fully account for these wide wealth discrepancies. For those with a high school degree (or equivalent) only, the white median household net worth is $101,200, while the Black median household net worth is $18,070—a ratio of 5.6. For those with a bachelor’s degree, the gap is significantly wider: $443,619 for white B.A. holders versus $32,000 for Black B.A. holders—a ratio of 13.9. Notably, the median white New Yorker with a high school degree still has a net worth over three times greater than the median Black New Yorker with a bachelor’s degree.

Chart 3

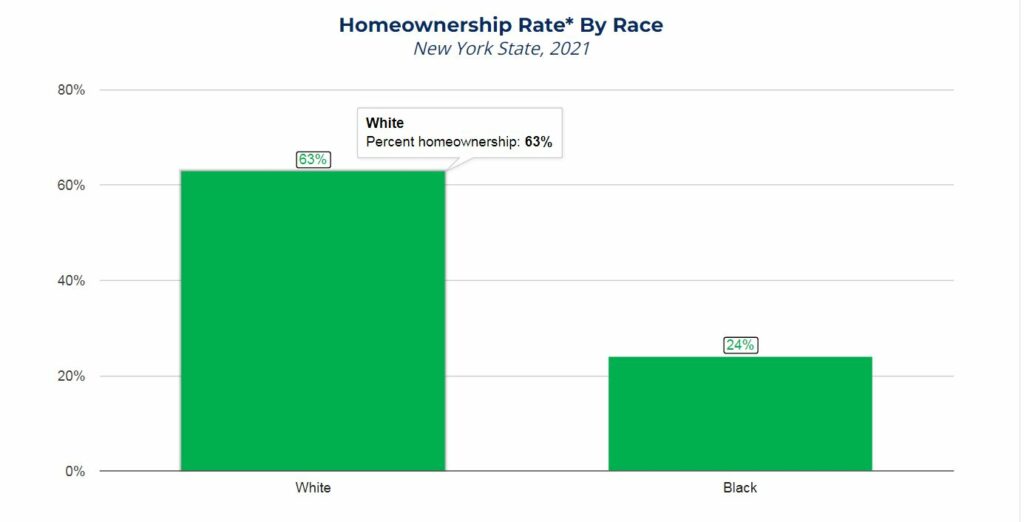

Looking more closely at three major components of wealth—homeownership, retirement assets, and student debt—we see that Black individuals fare significantly worse than white individuals on every front. Chart 4 compares the white versus Black homeownership rate* in New York State. While 63 percent of white New Yorkers own their home, only 24 percent of Black New Yorkers do. Given that homeownership has historically been the primary means for American families to build wealth and enter the middle class, the decades of racism which have marked our nation’s housing policies have had lasting impact on Black families’ ability to build wealth.

Chart 4

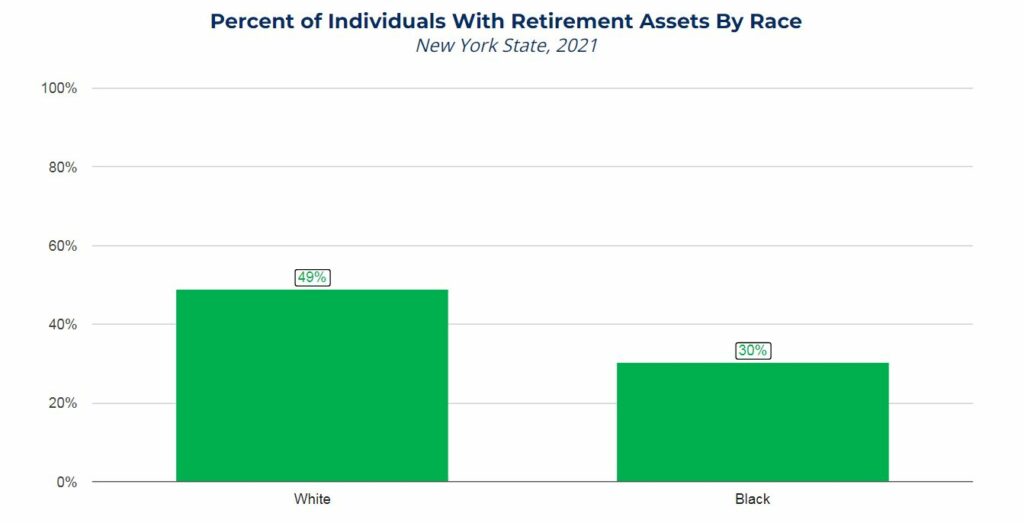

Retirement assets are another critical means for individuals and families to achieve economic security. Chart 5 reveals that white New York State residents are 62 percent more likely to have retirement assets than their Black counterparts, at rates of 49 percent versus 30 percent, respectively.

Chart 5

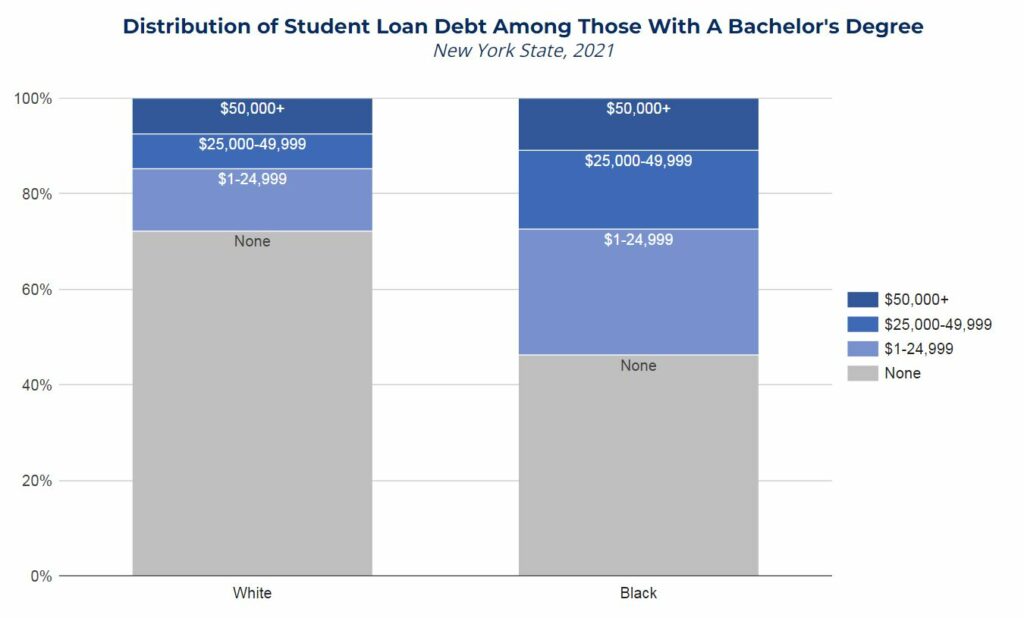

Student debt acts as another source of wealth inequity between Black and white New Yorkers. Among those with bachelor’s degrees, nearly twice the proportion of Black people (54 percent) have student debt compared with white people (28 percent).

Chart 6

Racial wealth inequality in New York City

While the Survey of Income and Program Participation utilized for the charts above provides highly detailed data on individual and household assets and liabilities, it does not specify respondents’ location beyond the state level. To better understand wealth disparities in New York City specifically, this review utilizes the American Community Survey (ACS). The ACS asks fewer questions about wealth, but does offer useful data on homeownership status and the possession of investment assets.

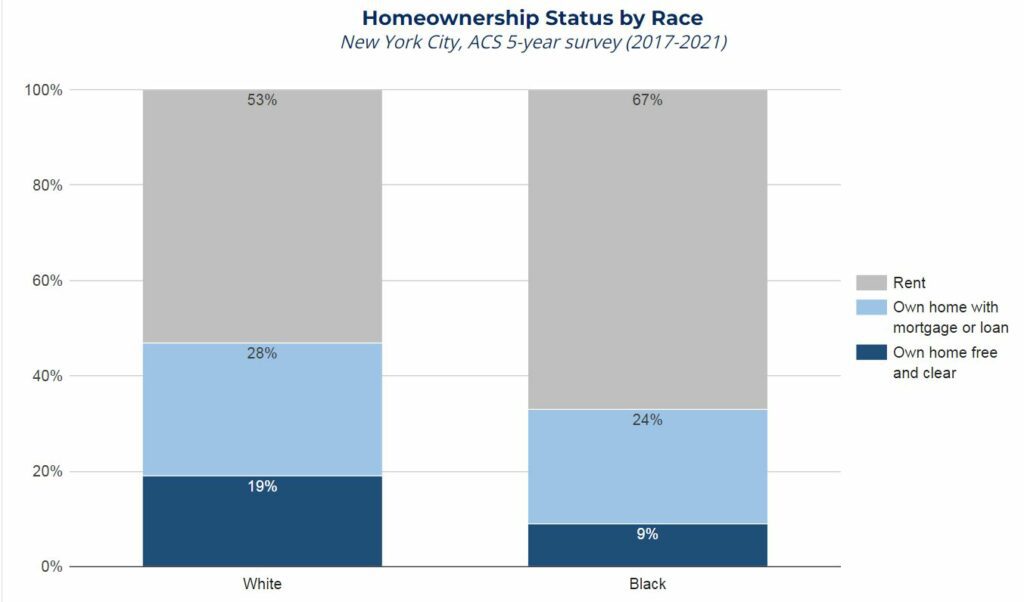

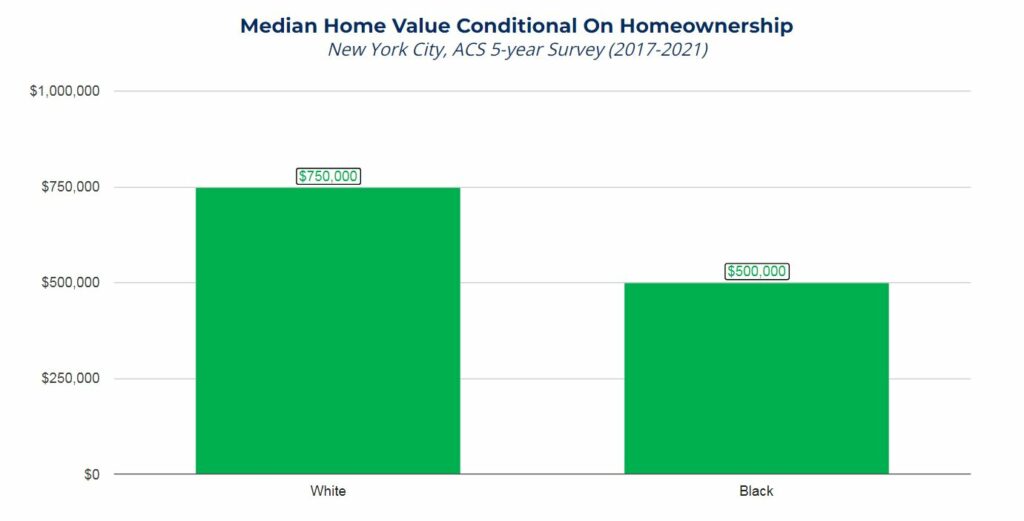

Per Chart 7A, Black New York City residents are 30 percent less likely to own a home than white New York City residents (at respective homeownership rates of 33 percent and 47 percent) and are less than half as likely to own their home free and clear. Moreover, chart 7B shows that the median Black New York City homeowner’s home value is significantly lower than that of the median white New York City homeowner.

Chart 7A

Chart 7B

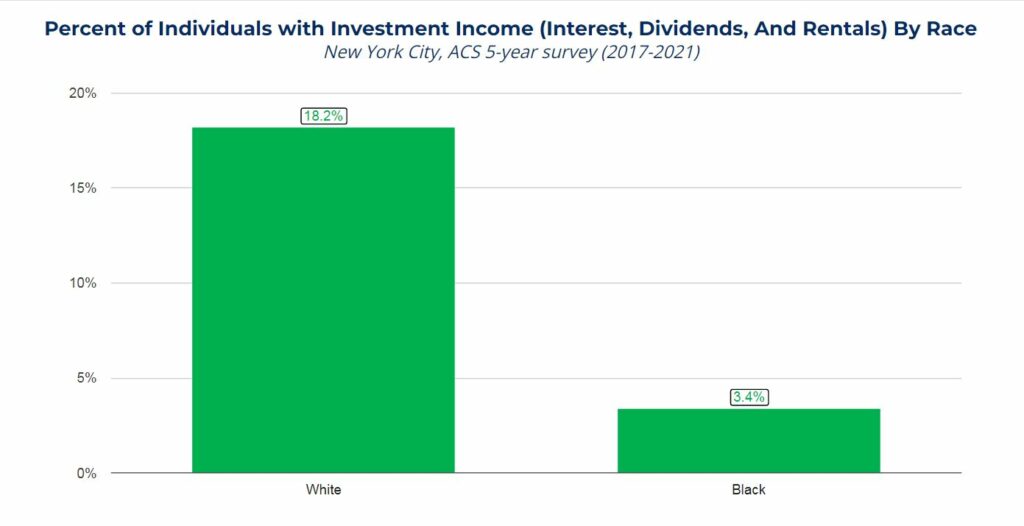

Finally, Chart 8 reveals significant discrepancy between Black and white New York City residents in the form of financial wealth. At respective investment asset ownership rates of 18 percent versus 3 percent, white New York City residents are almost six times more likely to have investment assets than their Black counterparts.

Chart 8

The solidarity dividend: how narrowing the racial wealth gap benefits us all

Racial wealth gaps like those identified above harm Black people, but the harm is not limited to them. In her book The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together, author and policy activist Heather McGhee describes the concept of a “solidarity dividend,” or the benefits that all people—not just groups of color—see when a polity confronts racial inequity.

The benefits come in any number of forms, from economic growth to public safety to community cohesion to educational achievement. For example, a 2017 report from the Chicago-based Metropolitan Planning Council estimated that if racial segregation in the Chicago metropolitan area were reduced to the national median level, the region would see its GDP boosted by $8 billion, its homicide rate decline by 30 percent, and its number of bachelor’s degree recipients increase by 83,000.

Evidence suggests that narrowing household wealth disparities, like those exposed above, and strengthening homeownership opportunities (the greatest contributor to household wealth for the majority of lower- and middle-income families[2]) would build stronger local economies and safer, more vibrant cities and towns. For example:

- A $10,000 increase in family wealth increases the likelihood a child will attend a flagship university by 2.0 percent, and the likelihood a child will complete college by 1.8 percent.[3]

- Greater economic security promotes public safety by reducing crimes associated with extreme economic precarity.[4]

- Increased home equity has a strong positive impact on families’ consumption, which in turn boosts economic growth. This impact is far larger than that associated with stock market wealth, which is overwhelmingly held by high net worth households.[5],[6]

- Increased housing wealth reduces gaps in educational resources and is associated with significant improvements in local school quality.[7]

In other words, addressing the racial wealth gap through potential reparations is not a “zero sum” effort. The evidence suggests that reducing racial inequality and increasing Black household wealth would likely increase the collective wealth and thriving of New Yorkers.

Conclusion

A long legacy of institutional racism in the United States has helped white families build wealth while often preventing Black families from doing the same. This analysis shows that New York State and New York City are no exception to the legacy of these policies. Given the severe and persistent racial wealth gap in both New York City and State—visible in virtually all major components of wealth, including homeownership, investment assets, retirement funds, and student debt—a commission to study these inequities, the potential for reparations remedies, and the benefits which would accrue to all of society as a result of narrowing the racial wealth gap is a worthwhile endeavor.

Endnotes

[1] While some of the data we report are individual-level characteristics (e.g., retirement assets, student loan debt), others are household-level (e.g., median household net worth, homeownership). Regardless, we tabulate all data on an individual level because race is an individual characteristic which can vary between different members of a household. So, for example, a surveyed Black individual will add a data point to the household net worth for Black New Yorkers even if their spouse is white, and vice versa. The most formal interpretation of our household net worth calculations is therefore: “The median Black person lives in a household with a net worth of X, while the median white person lives in a household with a net worth of Y.” Altering our analysis to include only one surveyed person per household did not significantly impact our results.

[2] Lovenheim and Reynolds (2012): “The Effect of Housing Wealth on College Choice: Evidence from the Housing Boom”

[3] Lovenheim and Reynolds (2012): “The Effect of Housing Wealth on College Choice: Evidence from the Housing Boom”

[4] Hanna Love, Brookings Institute (2021): “Want to reduce violence? Invest in place.” https://www.brookings.edu/articles/want-to-reduce-violence-invest-in-place/

[5] Bostic, Gabriel, and Painter (2009) “Housing wealth, financial wealth, and consumption: New evidence from micro data”

[6] Case, Quigley, and Shiller (2011): “Wealth Effects Revisited 1978-2009”

[7] Gilraine, Graham, and Zheng (2023): “Public Education and Intergenerational Housing Wealth Effects”

This piece was republished from New York Comptroller.