The toll on Alabama families of uncontrolled violence in Alabama Department of Corrections’ prisons

“My daughter has nightmares and wakes up screaming and crying because all she sees is her dad being beaten and strangled and screaming for help.” – Christy Martin, whose daughter’s father was killed in prison.

This story is part of Appleseed’s series “Cruel and Unusual” focusing on the people harmed by Alabama’s overreliance on excessive sentences, which trap people in deadly, dysfunctional prisons long after they have paid their debt.

By Eddie Burkhalter

On September 21, 2023

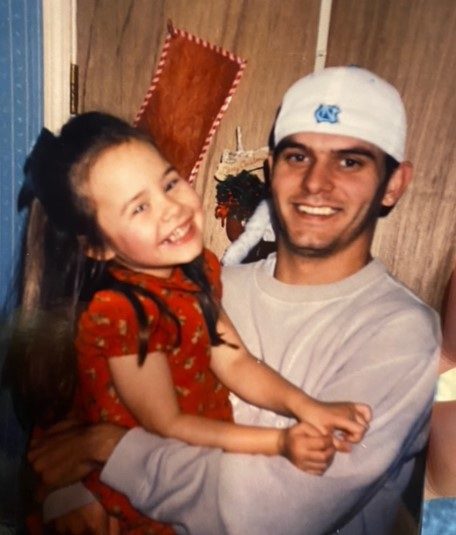

It’s difficult to know for certain what happened during the morning hours on Mothers Day 2023, in the segregation cell where correctional officers placed Christopher Mount along with another man at Easterling Correctional Facility, but for his two daughters what matters most is that Mr. Mount never came out alive.

Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) investigators believe the other man, William Smith, killed 44-year-old Christopher Mount in that cell. Smith, 48, was incarcerated after being convicted of choking his girlfriend to death in 2017. Mr. Mount was choked to death as well, according to his death certificate, which lists his cause of death as asphyxiation.

For an individual in need of extra protection to be killed in a segregation cell represents a serious institutional security failure. Prison segregation cells are supposed to provide safekeeping for people on suicide watch, for people with mental illness, for people being threatened with violence. But within Alabama prisons, basic safety is out of reach for many, many incarcerated people. Because it was out of reach for Mr. Mount, he leaves behind a family who loved him even through his struggles and longed for his return.

“My daughter has nightmares and wakes up screaming and crying because all she sees is her dad being beaten and strangled and screaming for help,” said Christy Martin, mother to Mr. Mount’s 17-year-old daughter, MaKayla. “We were supposed to have him home in our arms and not in an urn.”

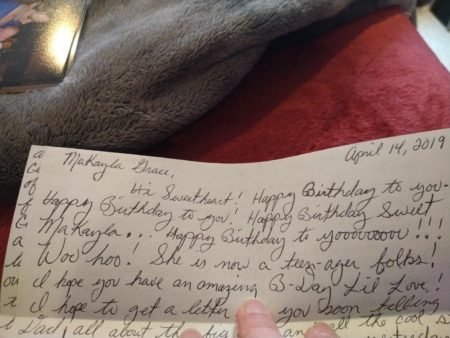

MaKayla Mount, is a member of the National Honor Society and will graduate from high school this fall. She’s been accepted into the University of Alabama at Birmingham and plans to become a physician. “These are things me and my dad talked about for years,” MaKayla told Appleseed. Her father was supposed to be around when all of her dreams came true, she said.

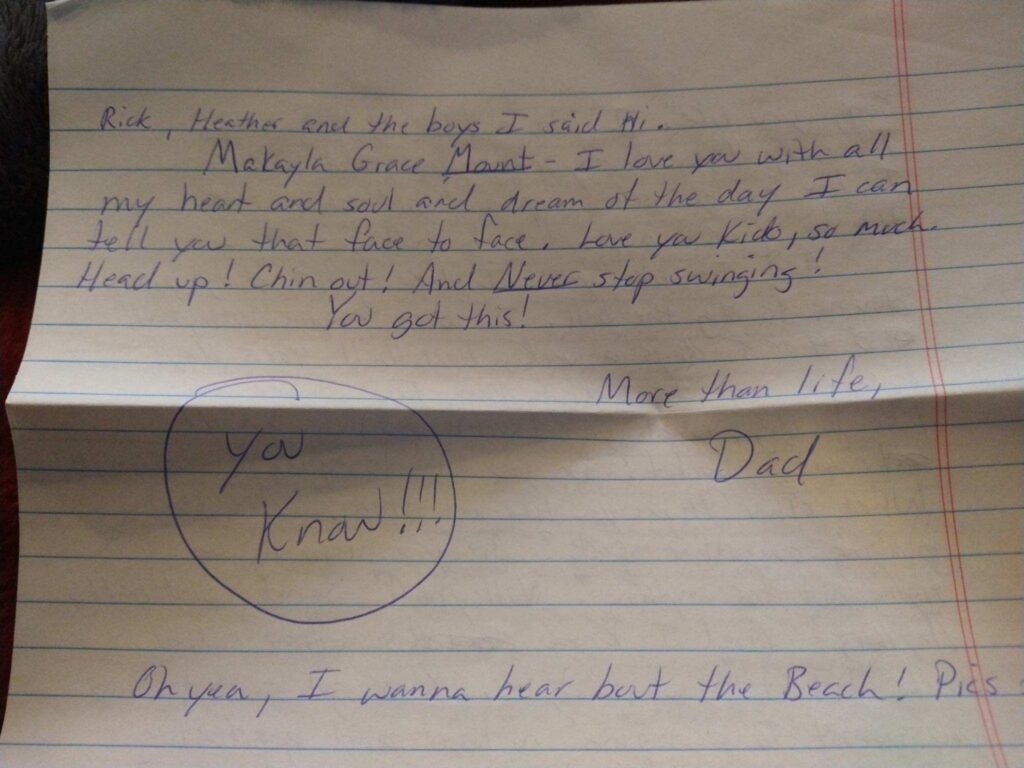

MaKayla said her father, even from behind bars, was a constant presence in her life. The two wrote letters constantly, talked by phone and she’d visit the prison in person to see him. She’d go to him for advice and he’d respond with honesty and support. “He was a great father, even from prison,” Martin said.

MaKayla would write a letter a day to her father about what was happening in her life, save them up and send a week’s worth all at once. He’d respond in letters that gave advice and support, and talked about what was happening in his life. “He helped build me up as a person,” MaKayla said.

The suspect in a prison homicide later commits suicide

The full story of what happened will likely never be known as the segregation cellmate, William Smith, is believed to have taken his own life 20 days later. “The prisons failed both of these men,” Christy Martin said. “So unnecessary. It could have been prevented. Chris should not be dead.”

The Alabama Department of Corrections declined to confirm to Appleseed that Mr. Mount and Mr. Smith were on suicide watch and cited “security reasons and for HIPPA violations.” The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act protects release of personal medical information for a period of 50 years after a person’s death. Mr. Mount’s family says both men were on suicide watch at the time, however.

Family members tell Appleseed that Mr. Mount’s mental health declined significantly following his second parole denial at an Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles hearing on Feb. 10, 2021. By then, he had served 15 years in Alabama’s violent, chaotic prisons.

The two deaths add to the growing ranks of people sentenced to Alabama prisons who die there. Through June, the last month for which ADOC has released numbers, there were 164 deaths in state prisons. During the same timeframe last year there were 92 deaths in prisons statewide, yet Alabama saw record prison deaths in 2022, when 270 incarcerated people died in custody.

Alabama Appleseed’s own tracking of prison deaths this year shows that at least 69 of those deaths were likely preventable, with 18 suspected homicides, 6 suspected suicides and 69 suspected overdose deaths, although those numbers are likely an undercount. Last year there were at least 95 preventable deaths in Alabama prisons.

ADOC doesn’t release timely data on prison deaths, and names aren’t released in department reports, leaving it up to journalists and others to gather those names and seek confirmation. The department’s quarterly reports publish data that reflects what was happening in prisons three months prior, so it’s difficult to gauge the current state of violence and death inside Alabama prisons.

It’s also difficult to gauge the impact that this loss of life has on the survivors, hundreds of Alabama families who’ve lost loved ones and lost faith in a criminal justice system that was supposed to provide rehabilitation and safety, not burials.

Parenting from prison

For a brief time before prison, Mr. Mount got to spend time with his youngest daughter. He was incarcerated at the Jefferson County Jail prior to his sentencing when MaKayla was born in 2006, but was freed on bond when MaKayla was three months old and was sent to prison five months later to serve his 30-year sentence.

MaKayla still has the letter her father wrote to her from the Jefferson County Jail. “I want you to have strong morals, and stronger convictions. I want you to be a well educated, independent, strong willed and very happy girl. And if you fall down 6 times, stand up seven,” he wrote to her.

In a letter to MaKayla when she was older, her father wrote about his wishes to once again be free and with her. “MaKayla Grace Mount – I love you with all my heart and soul and dream of the day I can tell you that face to face,” Mr. Mount wrote. “Love you kiddo so much. Head up! Chin out! And never stop swinging! You got this!”

MaKayla said her father did what was expected of him while in prison so that he could return to her, but explained that it came to nothing. “He had rehabilitated himself. In that second parole hearing, when he was denied, that was his death sentence right there,” MaKayla said.

“Prison is not supposed to be easy, but prison is not supposed to be a death camp. You’re not supposed to starve. You’re supposed to be taken care of medically, mentally,” Martin said. Both mother and daughter explained that Alabama prisons are failing to rehabilitate, and lives are being lost.

District Judge Myron Thompson in his 2021 opinion in the long-running Bragg V. Dunn lawsuit over ADOC’s inadequate mental health care in prisons sounded an alarm over severe staff shortages, overpopulated prisons, the failure to identify suicide risks adequately and inadequate treatment and monitoring to those who are suicidal.

Thompson wrote of the suicide of Jamie Wallace, one of the plaintiffs in the class-action lawsuit, who killed himself days after Wallace testified in a hearing. Wallace had been released from suicide watch, received no followup care and killed himself two days later, according to the court filing. Thompson wrote that Wallace’s suicide was “powerful evidence of the real, concrete, and terribly permanent harms that woefully inadequate mental-health care inflicts on mentally ill prisoners in Alabama” and yet he noted in his 2021 opinion that “In the four years since, at least 27 more men in ADOC’s custody have died by suicide.”

“Prisoners do not receive adequate treatment and out-of-cell time because of insufficient security staff to supervise these activities. They are robbed of opportunities for confidential counseling sessions because there are too few staff to escort them to treatment, forcing providers to hold sessions cell-side,” Thompson continued. “They decompensate, unmonitored, in restrictive housing units, and they are left to fend for themselves in the culture of violence, easy access to drugs, and extortion that has taken root in ADOC facilities in the absence of an adequate security presence.”

The U.S Department of Justice’s 2020 lawsuit against Alabama and ADOC alleges that the state “fails to provide adequate protection from prisoner-on-prisoner violence and prisoner-on-prisoner sexual abuse, fails to provide safe and sanitary conditions, and subjects prisoners to excessive force at the hands of prison staff.” The trial is set for November 2024.

Even a victim knew he needed drug treatment

At the time of his death Mr. Mount had served almost 17 years of a 30-year sentence after pleading guilty to a string of crimes in 2005 and 2006, all motivated by substance use. In 2005, Mount attempted to have an altered prescription for Percocet filled at a Trussville Walmart, according to court records, and was charged with Attempt to Commit Controlled Substance Crime. Later that year, he was charged with first-degree robbery and attempted assault, which occurred while he was fleeing by car and dragged a police officer who was attempting to stop him across the parking lot. That same day Mr. Mount stole tools from his workplace and broke into a neighbor’s home, where he was caught by the neighbor while holding her jewelry. He was charged with first degree theft of property and third degree burglary for those crimes. He pleaded guilty to all of those charges in August 2006.

Mr. Mount’s neighbor in that theft charge wrote a letter to the court on his behalf. The two families had been friends for more than 20 years, and Mr. Mount often helped his neighbors when their own son wasn’t at home to do so, the letter reads. “He is still a very young man and has a lot of good left in him. Drugs can ruin anyone,” the neighbor wrote, asking the court to get him help for his addiction problem so that he can get back to care for his newborn daughter. “Life is very precious, and once it’s gone and the years have passed – it cannot be brought back,” she wrote. “Please send him to a facility where he might get the help he so desperately needs.”

Instead, Mr. Mount found himself in Easterling prison, where officers bring in the drugs that drive the violence and death inside. Easterling prison was at 188 percent capacity the month that Mr. Mount was killed. That same month three other men died inside Easterling, according to ADOC’s quarterly report. So far this year ADOC has opened investigations into 12 deaths at Easterling. During the entire year that he entered prison in 2007, ADOC recorded one death in Easterling.

Brittani Mount, 27, MaKayla’s half-sister, was 10-years old when her father was sent to prison. She told Appleseed she was getting breakfast the morning she got a call from the investigator handling her father’s death. “I immediately knew. He didn’t even get two words out and I said, he’s gone, isn’t he, and he said yes,” Ms. Mount said. “I felt like that 10-year-old little girl again who just lost him, all over again.”

Losing him to prison was hard for her 10-year-old self to understand, she said. Her grandmother, Mr. Mount’s mother, passed a decade ago and the death hit her father very hard. Brittani was born when Mr. Mount was just 17. She described her father as a good person with a big heart. “I remember eating hot wings with him and sitting in front of the TV and watching Scooby Doo,” she said. “He took me to movies and we had so much fun together. I got the Chris who was free and my sister didn’t.”

Brittani said she and her father would sing together, and she’d memorize the words to their favorite songs by the recording artist Eminem. “I was very close to him. I was a big daddy’s girl,” Brittani said. “Everybody makes mistakes, and he just made a couple mistakes. It’s just so hard to think about. I think this is the first time I’ve actually talked about it,” she said.

She believes her father’s sentence was far too harsh, and the lengthy sentence and parole denials cost him his life and removed any chance the two would reunite in person. “He did his time a long time ago,” she said.

“Never seen this many people die in one prison”

While Appleseed gathered information on the deaths of Mr. Mount and Mr. Smith, more tragic news came. September 7, a week after being beaten by several other incarcerated men, and two days after his wife said she paid those same men who had extorted him with the threat of death, Tommy Tunstall died in his cell at Donaldson Correctional Facility.

Appleseed began corresponding with Mr. Tunstall in 2022 as part of efforts to investigate the cases of older, incarcerated people serving life without parole under Alabama’s Habitual Felony Offender Act. Mr. Tunstall frequently wrote Appleseed lawyers with updates on living conditions at Donaldson.

In September of last year, Mr. Tunstall sent a detailed letter about the lack of security staff at Donaldson and the increasing number of deaths. “All of our lives are in danger, people are already dying off the radar here, but from what and why? I’ve never seen this many people die in a month,” he wrote. “Something’s not right. That’s for sure. I’ve been incarcerated 28 years day for day and I’ve seen it, but never seen this many people die in one prison.”

“I have a beautiful family waiting on me out there and God knows I want to be out there to spend time with them. I have a home plan and a job plan,” he wrote in February, 2023. “April the 14th of this year, I’ll be 54 years old. … I just want to get out, be a positive factor for the environment, work, take care of my wife, and live life one day at a time.”

His death remains under investigation pending the results of an autopsy, according to ADOC. His wife, Theresa Tunstall, told Appleseed that she is certain he would not harm himself. Mr. Tunstall’s cellmate, however, told Appleseed he found Mr. Tunstall hanging by his belt from the top bunk, took him down and laid him across his bed and called for officers. The cellmate told Mrs. Tunstall the same version of events.The cellmate said Mr. Tunstall told him the night before he died that he was “tired” and had already served “too many years.”

This piece was republished from the Alabama Appleseed.