What Drives Poor Quality of Care for Child Diarrhea? Experimental Evidence from India

By ZACHARY WAGNER, MANOJ MOHANAN, RUSHIL ZUTSHI, ARNAB MUKHERJI, AND NEERAJ SOOD

9 Feb 2024

INTRODUCTION

Diarrhea is a leading cause of death in children, with nearly 500,000 young lives lost to diarrhea each year. Almost all these lives could be saved with a low-cost and widely available treatment: oral rehydration salts (ORS). However, at the present time, nearly half of diarrhea cases around the world do not receive ORS. Millions of young lives could be saved if we can find ways to increase ORS use.

Even when children seek care from a health care provider for their diarrhea, as most do, they often do not receive ORS. Surprisingly, most health care providers in developing countries know that ORS is a lifesaving and inexpensive treatment for child diarrhea, yet few prescribe it. This know-do gap has puzzled experts for decades and cost millions of lives.

RATIONALE

To develop interventions that increase ORS prescribing, we must have a clear understanding of why providers do not prescribe ORS even though they know it is the standard of care. There are several leading explanations. First, providers might think that patients prefer non-ORS treatments (e.g., antibiotics) or dislike ORS because of poor taste, lack of observable symptom relief, and perceptions that ORS is not a real medicine. Second, providers could be responding to financial incentives to sell more-profitable alternatives. ORS is inexpensive, and antibiotics generate nearly double the profit. Finally, providers often have ORS stock-outs (out-of-stock events) and might prefer to dispense something they have in stock to not lose out on the sale. Each of these potential barriers to ORS prescribing suggests a different solution.

We used a randomized controlled trial to simultaneously study the role of these three leading explanations for the underprescribing of ORS. More than 2000 providers across 253 medium-sized towns in the Indian states of Karnataka and Bihar participated in the study. To measure the effect of perceived patient preferences, we had standardized patients (actors trained to act as patients) make unannounced visits where they presented a case of diarrhea for their 2-year-old child, and we randomly assigned whether they expressed a preference for ORS, a preference for antibiotics, or no preference. To measure the effect of financial incentives, some of the standardized patients assigned to the no-preference arm informed the provider that they would purchase medicines from a different location, thereby eliminating the provider’s financial incentive to recommend more-lucrative treatments. Finally, to estimate the effect of ORS stock-outs, we randomly assigned all providers in half of the 253 towns to receive a 6-week supply of ORS.

RESULTS

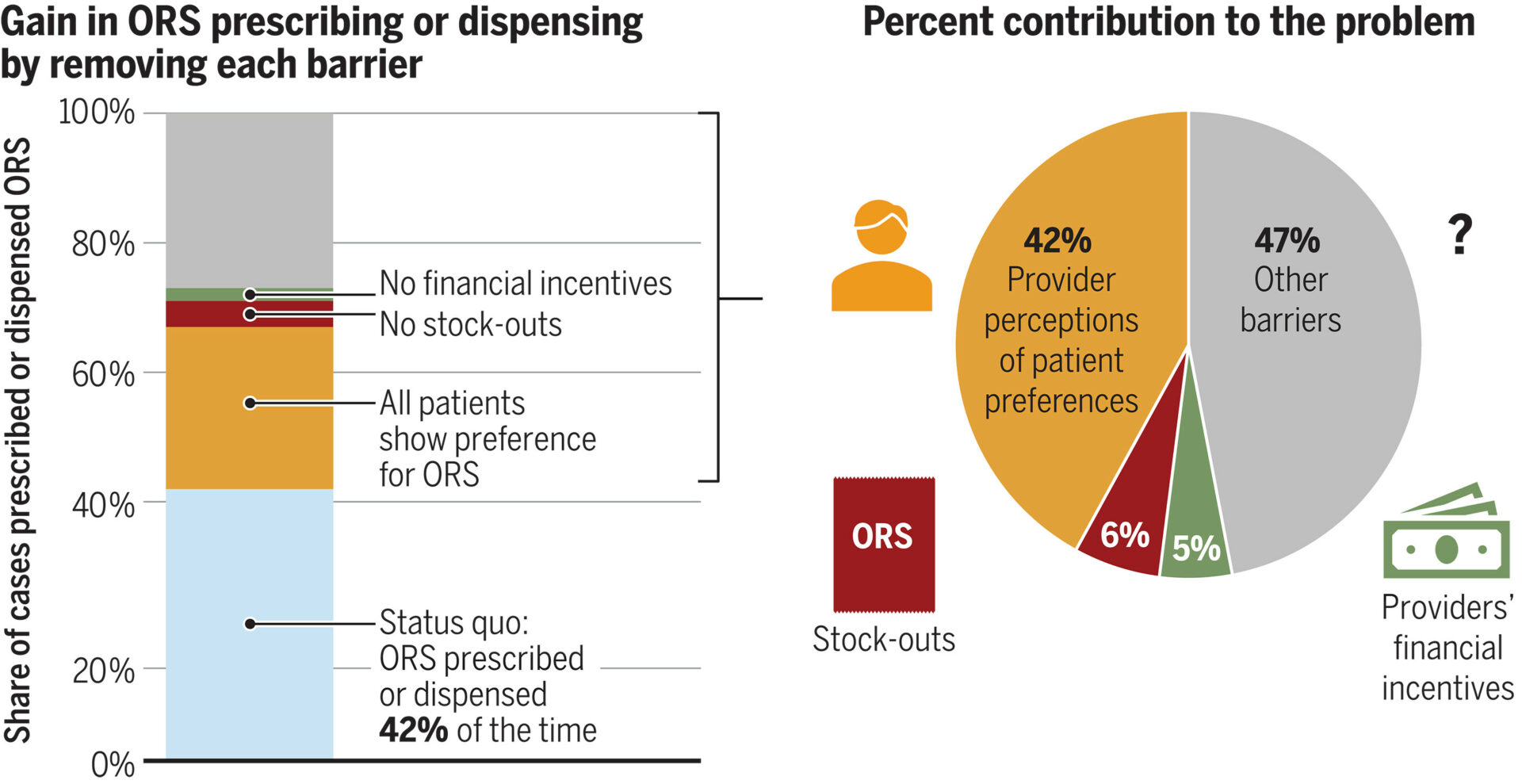

We found that having standardized patients express a preference for ORS increased ORS prescribing by 27 percentage points compared with no preference; 28% prescribed or dispensed ORS when standardized patients expressed no preference, and 55% prescribed or dispensed ORS when standardized patients expressed an ORS preference (96% increase). We show that this is mainly because providers think only 18% of their patients want ORS on average, when, in reality, ORS was the most preferred treatment reported by patients in household surveys. Eliminating stock-outs increased ORS provision by 7 percentage points on average and by 17 percentage points among clinics that sell, rather than prescribe, medicine. Eliminating financial incentives to sell more-lucrative medicines had no effect on average but did increase ORS prescribing at pharmacies by 9 percentage points. By combining these results with the prevalence of each barrier estimated through provider and household surveys, we estimate that provider misperceptions that patients do not want ORS explain 42% of underprescribing, whereas stock-outs and financial incentives explain only 6 and 5%, respectively.

CONCLUSION

Provider misperceptions that patients do not want ORS play the biggest role in the underprescribing of ORS and are 6 to 10 times more important than financial incentives or stock-outs. These results suggest that interventions to change provider misperceptions of patients’ ORS preferences should be aggressively explored because they have the potential to substantially increase ORS use. These interventions could target patients or caretakers and encourage them to express an ORS preference when they seek care, or they could target providers directly and inform them that ORS preferences are more common than they think.