What happens when your loved one goes missing?

A history of neglect, botched investigations, and flawed data reveal systemic issues with the way police treat missing person cases.

By Trina Reynolds-Tyler and Sarah Conway

On November 14, 2023

This story is part of the Chicago Missing Persons project by City Bureau and Invisible Institute, two nonprofit journalism organizations based in Chicago. Read the full investigation and see resources for families of the missing here.

Shantieya Smith was a protector in her North Lawndale home, where three generations lived under one roof—the cousin you’d call when there was trouble, who’d walk her young daughter to school every day, and whose cherry-red or bottle-blonde weaves mirrored her bright energy. So when the 26-year-old walked out her front door on a warm May afternoon in 2018 to run a quick errand, her mother, Latonya Moore, didn’t think much of it.

“It was a trip that was supposed to be so fast she didn’t even bring her cell phone,” Moore remembers of the last moment she saw her daughter alive.

In fact, it was the beginning of a two-week odyssey where Moore would confront Chicago police about their response to the case, hold press conferences to accuse police of inaction, and even call out then police superintendent Eddie Johnson himself. She would collect evidence on her own and scrape together as many community resources as possible to search for her missing daughter.

Two weeks later, Smith’s body, disposed and desecrated, was found in a nearby abandoned garage. Her case joined the 99.8 percent of missing person cases from 2000 to 2021 that Chicago police have categorized as “not criminal in nature.”

“I am still getting the runaround to this day,” Moore says, years after Smith’s body was found. A killer has still not been charged. If police had taken her case seriously, things might be different, she says. “When it comes to justice, I get angry. I get to the point of, why me?”

Systemic issues

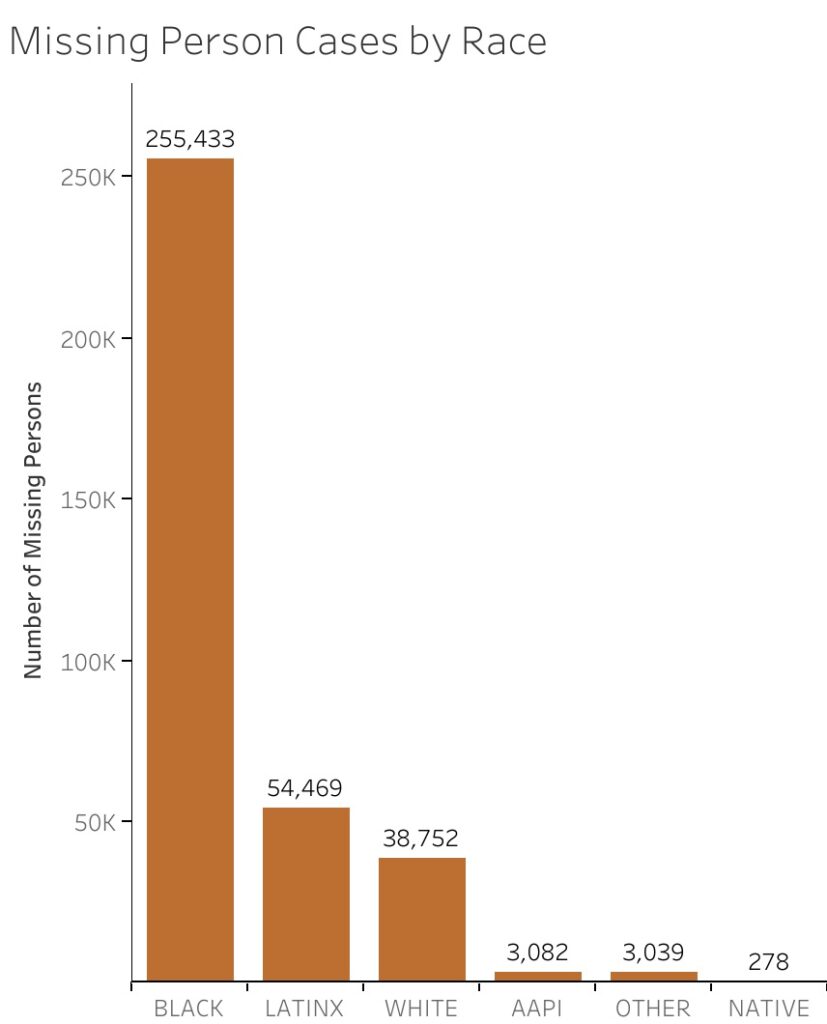

Chicago’s missing person crisis is a Black issue.

Black people have made up about two-thirds of all missing person cases in Chicago over the past two decades, and the vast majority of these cases are for Black children under the age of 21. In particular, Black girls and women between the ages of ten and 20 make up nearly one-third of all missing person cases in the city, according to police data, despite comprising only two percent of the city population as of 2020.

Already distrustful of police due to decades of racial profiling and abuse—including a legacy of police torture and a federal investigation that led to a still-active court-mandated reform plan—Black Chicagoans say that police do not act urgently or sufficiently to find their missing loved ones.

While police officials have publicly claimed that services for families are equal and fair across race and zip codes, massive gaps in missing persons data make it impossible to prove, according to a two-year investigation by City Bureau and the Invisible Institute. Instead, interviews with current and former police officers, national experts, and researchers, along with dozens of anecdotes from impacted family members, reveal systemic problems with the way police treat missing person cases:

- Police officers routinely deny or delay people who try to report their loved ones missing, against Illinois state law and police policy.

- Families of the missing say officers are dismissive of their cases, neglect their investigations, and stigmatize their loved ones—including multiple cases where police declined to investigate key leads or lost evidence, leaving families to conduct their own searches.

- Analyzing police data on missing person cases from 2000 to 2021, reporters found discrepancies that call into question the department’s data-keeping practices—making it difficult to see how many cases are related to crimes, how long it takes for police to respond to a missing person report, or even to confirm how many missing people returned home safely.

- In four cases, detectives explicitly noted the missing person had returned home, despite family members saying their loved ones never returned home alive.

Not only does this erode the community’s already thin trust in Chicago police, but even sources within the department say bad management and inefficient systems leave detectives burned-out and unable to help families in need. It also means a recently formed state task force examining the issue of missing women and girls in Chicago will face a near-impossible hurdle in linking missing person cases to crimes like murder and human trafficking.

In a moment when missing person cases are garnering more attention, both nationally and locally, public officials and community members agree that tackling the missing persons issue will require holistic solutions: from changing state laws, to retraining police officers and allocating resources to missing persons investigations, to funding community programs like safe houses, mental health services, and neighborhood searches. But filing a police report is many people’s first step when their loved one goes missing—and community members want to know what they could, and should, expect from police.

A spokesperson in Mayor Brandon Johnson’s office recognized inequities in how police handle missing person cases in Chicago. “The historical disparities that exist in our city when it comes to solving missing person cases among Black and Brown Chicagoans—and Black women, in particular—is an example of the lack of visibility for marginalized communities,” says spokesperson Ronnie Reese. “We need to see people in order to care for them, and ultimately protect them from wicked systems that have been a threat to these communities for generations.”

“The police failed me”

Official police case data is limited, but interviews with over a dozen families whose loved ones have gone missing, as well as an analysis of police complaint data, tell a clear story: Community residents, especially Black Chicagoans, say police are disrespectful, negligent, and dismissive when it comes to their cases.

City Bureau and the Invisible Institute spoke with multiple people who say police told them—contrary to state law and department policy—they could not file a missing person report or that they needed to wait 24 hours before filing.

An analysis of police complaint records from 2011 to 2015 found 17 complaints against officers for allegedly refusing to file missing persons reports. None of the officers named in these complaints were disciplined.

“They were saying you have to wait 48 hours before you can actually report the person missing,” says Reverend Robin Hood, who remembers hearing this from police officers starting in the 1990s. The west-side activist and preacher has raised awareness and led community searches for missing Black girls and women for decades.

In response, Chicago police spokesperson Thomas Ahern wrote in an emailed statement: “The Chicago Police Department takes each missing person report seriously and investigates every one consistently. Under state law, CPD is required to take every missing person report regardless of how long the person has been absent or who is submitting the report.”

Some families believe that if police had acted more urgently, their loved ones might still be alive. On July 24, 2016, Shante Bohanan called her sister and said she was being held against her will. Bohanan’s boyfriend had recently died in a shooting, and the 20-year-old had gone to her boyfriend’s family’s house in order to grieve, family members tell City Bureau and the Invisible Institute. A police document stated that during the phone call, Bohanan told her sister she had a “gun held to her head.”

Worried for her safety, Bohanan’s mother, Tammy Pittman, says she attempted to report her daughter missing that evening, but officers urged her to wait another 24 hours. It wasn’t until the next evening that officers searched the home where Pittman suspected her daughter was being held; they found nothing. A day later, Bohanan’s body was found naked inside a black plastic garbage bag in a nearby garage.

“The police failed me. Even though she’s dead, she’s gone, I don’t have no answers and that’s what hurts most of all,” Pittman says, adding that she hasn’t heard from detectives in five years.

Shirley Enoch-Hill believes she will never find out what happened to her daughter, Sonya Rouse, who dreamed of being a news anchor. When Rouse went missing in 2016 at age 50, she immediately suspected Rouse’s boyfriend, who she claims physically abused her daughter throughout their relationship.

But according to police documents, detective Brian Yaverski did not interview the boyfriend even though he was in custody at Stateville Correctional Center for several months. Eventually, he was released, and almost one year later died of a suspected fentanyl overdose. Yaverski never interviewed him.

Enoch-Hill remembers crying when she heard Rouse’s boyfriend died because she felt the truth of what happened to her daughter was gone forever. “There is no closure. . . . It was like she disappeared off the face of the earth,” she says. “If you’re Black and you come up missing, nobody cares.”

Over a dozen families interviewed for this story say they felt neglected and disappointed in CPD’s handling of their loved ones’ cases—services a majority believed were bad because their relatives were Black and Latino.

Even after Moore, Smith’s mother, convinced officers to accept a missing person report for her daughter on May 29, 2018, she was afraid police were not taking her case seriously. Smith had uncharacteristically left her cell phone at home—but police never collected it.

“Police weren’t doing what they were supposed to do, so I had to do it on my own,” Moore says. She even ended up calling and texting a man that Smith had been last seen with—a man she believed to be her daughter’s murderer.

Like several families who spoke to reporters about their missing loved ones, she organized her own search with the help of a local community organization, even hosting a press conference to call out the police’s lack of response.

Downplaying the case, police superintendent Eddie Johnson hosted his own press conference. “The two young ladies we are speaking about were involved in narcotics sales, prostitution, using narcotics together—we do know that,” Johnson said, referring to Smith and Sadaria Davis, who was found dead earlier that spring. However, Moore says her daughter did not use drugs. City Bureau and the Invisible Institute could not independently verify a connection between Smith and Davis outside of the person with whom they were last seen. The medical examiner later said Smith had no illegal drugs in her body.

Black families and advocates for missing person cases say police officers often use dismissive language, sometimes citing personal details about the missing person in a way that places the family and the potential victim at fault.

“The whole narrative is that she’s not deserving to be looked for or deserving to be protected,” says La’Keisha Gray-Sewell, founder and executive director of the Girls Like Me Project, which empowers Black girls in Chicago. “Instead police will say she was on drugs or she was a, quote, unquote, prostitute.”

But even Johnson himself has come to understand the terrible consequences of that attitude, eventually apologizing to Moore for what he said at that 2018 press conference. “Just [because of] who they are or where they come from or their lifestyle, that doesn’t mean the police shouldn’t take it as serious, because we should,” the former top cop told City Bureau and the Invisible Institute in a January interview. “Somebody loved that person.”

Hidden in police data

Between 2000 and 2021, the Chicago Police Department claims that just over 343,000 (99.8 percent) of all missing person cases were closed and not criminal in nature, indicating the person was “likely found.” In fact, police data from this time period identifies fewer than 300 missing person cases that were reclassified as a crime and only ten as homicides.

This does not include Smith’s case, because police labeled her case “non-criminal,” then opened a separate police investigation into her death not linked to her original case in CPD’s missing persons data.

“If it’s true that police are not linking missing person cases with criminal investigations, well, that’s obviously bad record-keeping,” says Thomas Hargrove, a researcher and retired investigative journalist with the Murder Accountability Project. Inaccurate data makes it difficult for police or public officials to fully understand and effectively tackle the missing persons problem in Chicago, according to Hargrove, Matthew Wolfe, and Tracy Siska, all researchers who specialize in police data.

City Bureau and the Invisible Institute identified 11 cases (including Smith’s) that were miscategorized as “closed non-criminal” in the missing persons data despite being likely homicides—more than doubling the number of official homicides in missing persons police data. This figure includes the cases of two Black teenage girls who were sexually assaulted and then murdered—14-year-old Takaylah Tribitt, who ran away from a north-side shelter and was later found shot to death in a Gary, Indiana, alley, and 12-year-old Jahmeshia Conner, who was found strangled to death in a West Englewood alley.

“If you’re trying to understand how many of the missing person cases within your city are homicides, obviously you should keep accurate records about that,” says Wolfe, a journalist and doctoral candidate in sociology at New York University, where he studies police missing persons data across the country.

“The mistakes that humans make with the data [are] the primary driver of this real problem everywhere. . . . You want those records to be linked [or] you can’t come up with meaningful analysis,” adds Hargrove.

Reporters found these cases by searching for murder charges and news stories and cross-referencing the names of the missing; it’s unclear how many missing person cases that never resulted in murder charges or media coverage were miscategorized in this manner. In Chicago, police arrest somebody in just under a quarter of all homicide cases (though the agency is under fire for claiming to “clear” nearly half of homicide cases in 2021, according to a CBS Chicago report).

“If you’re trying to understand how many of the missing person cases within your city are homicides, obviously you should keep accurate records about that.”

While in some cases this may be due to clerical error, City Bureau and the Invisible Institute also identified four cases where police actually wrote, in their own words, that the missing person was returned home safely, even though they were not.

In the case of 61-year-old Linzene Franklin, who was reported missing in 2011, a detective claimed in a 2014 Chicago police report that she had returned home without incident. In reality, Franklin died of a heart attack at a north-side bus stop in 2013 and was buried as an unidentified person. Her body remained in a south-side Roman Catholic cemetery for nine years before Cook County police connected the two cases and alerted Franklin’s family. Franklin’s daughter told Cook County police she hadn’t seen her mother since 2011.

The Cook County Sheriff’s Office’s Missing Persons Project closed Linzene Franklin’s case in 2022 after successfully matching Franklin’s DNA with a family member’s. Commander Jason Moran, who leads the team, confirmed in an interview with City Bureau and the Invisible Institute that the CPD had prematurely closed the case.

After 16-year-old Desiree Robinson ran away from her grandparents’ home in late November 2016, detectives reported in a police investigative document several weeks later, “The missing has been located. No indication the missing was a victim/offender.” However, her grandfather Dennis Treadwell says Robinson never returned to his home nor was he contacted by police about her whereabouts prior to her murder. On Christmas Eve that same year, a man murdered Robinson, who had been the victim of sex trafficking on Backpage.com, after she refused to perform a sexual act for free in a garage in Markham, Illinois, while her sex trafficker slept outside in a parked car, according to a Chicago Sun-Times report.

A police spokesperson says, “The Chicago Police Department takes these cases seriously in hopes that the missing individuals are able to return home to their loved ones safely. Each missing person case is thoroughly investigated based on the evidence available. We will continue to investigate all open missing person cases as we work to locate those who are missing.”

Siska, founder of the Chicago Justice Project, adds that errors in CPD data collection are common. He found similar issues with data on how police officers respond to 911 calls. “It is an institutionalized problem,” he says. In 2022, a Chicago Sun-Times investigation revealed how half of murders considered “solved” by CPD did not result in an arrest, despite police officials publicly touting the high “clearance” number.

The issue of missing persons, including how police handle these cases and whether bias plays into the quality of police services and its connection to violence, is both complex and understudied due to the poor quality of police data nationwide, experts say.

Chicago police records also show that, in the last five years, 45 percent of cases are missing a key data point about the time and date police arrive to investigate these cases. And police sources told City Bureau and the Invisible Institute the missing person case report is one of the few remaining incident reports done on paper, likely resulting in poor data collection.

These cases lead to important and unanswered questions: How many people in the city of Chicago remain missing despite officers concluding that the person had “returned home?” How many are victims of violent crimes, with their bodies never found or identified by the very department tasked with protecting and serving them? And while this investigation focuses on missing persons who were killed, how many more cases included terrible crimes that left the victim alive and traumatized?

Solutions should center survivors

Current and former law enforcement officials tell reporters they think the department can improve the way it handles missing person cases. These changes range from improving data collection to providing more resources for investigations and retraining officers for cultural sensitivity.

Detectives are already operating with a high caseload, and missing person cases are not a political priority within the department, sources say. “The most important thing for politicians is the safety of the city, and that means shootings. Everything else gets prioritized less than that,” says a current police officer who asked to remain anonymous due to fear of reprisal.

One former missing persons detective, who also asked to remain anonymous, says detectives are strapped for time and often have to rely on phone calls, not in-person detective work, to parse through what’s happened in a case.

Retired commander Patricia Casey, who oversaw juvenile missing person cases from 2019 to 2021, says CPD should invest in a specialized missing persons unit where police “would investigate [missing persons] a lot deeper than we do now.” While on the force, she advocated within the department to collect more information on crimes related to missing persons, including sex trafficking. She says the reform failed due to a lack of political will inside of CPD headquarters, a sentiment echoed by other police sources who chose to remain anonymous.

Casey was among several CPD sources who say the department needs to digitize its missing person incident form. A digitized system (common at other large police departments, like Washington, D.C.’s and Miami’s) would ensure data is collected and cases could reach detectives more quickly, sources say.

Moran, of the Cook County Sheriff’s Office’s Missing Persons Project, says officers should be more vigilant when closing cases and should take them seriously. For instance, he requires an in-person verification from his own officers when they confirm a missing person is located. “Look at it from the standpoint of this missing person that’s been reported to you [who is] one of those bodies laying on a table down at the morgue,” he says.

Six years ago, Hargrove identified 51 murdered women in Chicago as potential victims of a single serial killer. His theory led to a cascade of headlines and evening news stories, bringing the issue of missing persons to broader public attention and stepping up anxiety in Black neighborhoods where these cases were well-known. Since then, police investigations have reexamined DNA evidence and determined it was unlikely all 51 women were murdered by the same person.

Local advocates close to the issue still believe there are multiple serial killers targeting Black women and girls. The victims identified by Hargrove were almost all Black women, often strangled or asphyxiated, their bodies discarded in south- or west-side abandoned buildings, alleys, trash cans, lots, and parks. Many had histories of substance use and sex work.

While some solutions are possible at the department level, both police sources and community members are quick to point out that other community resources are necessary to fully address the root causes of why people go missing.

Credit: Sebastián Hidalgo for City Bureau & Invisible Institute

“Redlining, racism—we literally create the landscape for murdering Black women and girls in Chicago,” says Beverly Reed-Scott, an advocate for the 51 murdered women identified by Hargrove, who underpins the serial killer theory.

Advocates like Reed-Scott say the problem extends beyond violent individuals who need to be brought to justice. Local grants could support community- and family-led missing persons searches, safe houses for people at risk for exploitation and trafficking, as well as mental health services.

As for the new state task force on the subject, “We’re just looking for information and patterns and see if we can put together a profile and save lives,” says state senator Mattie Hunter, who cochairs the group. The task force does not have its own budget, but both Hunter and her cochair, state representative Kam Buckner, hope new legislation will bring in more resources after the group presents its findings to the governor and legislature at the end of 2024.

It’s not unprecedented. This year, based on its own task force’s recommendations, Minnesota created an Office of Missing and Murdered African American Women with a $1.24 million budget to assist with cold cases and support domestic violence and human trafficking prevention. Montana, which had a task force focused on missing Native women, received a $25,000 Montana Department of Justice grant to create a state portal for missing person cases to collect better data and share resources with families.

In Chicago, Mayor Brandon Johnson pledged to establish a missing persons initiative that would train civilians in trauma-informed crisis response. “Our administration is committed to seeing these individuals and their families, investing in them, and providing the resources needed to solve these cases and bring justice and closure to loved ones and communities,” says Reese, the mayor’s spokesperson. Johnson’s office did not respond to an interview request for more details on this plan.

Advocates like former CPD homicide detective Gerald Hamilton, who in his retirement has supported searches for missing Black women and girls, say the city could directly fund community- and family-led missing persons searches in Chicago to bridge the gap in police services.

Regardless of what form future resources and initiatives take in Chicago, “Victims and victims’ families need to be centered to bring recommendations,” says Shannon Bennett, executive director of Kenwood Oakland Community Organization, which hosts the annual We Walk for Her march to raise awareness about the issue. “That’s why I’m leery of any recommendations coming in from people who haven’t had the lived experiences.”

But that participation will be a challenge to garner when so many families feel the system has let them down.

Five years after her daughter’s death, Moore was asked if she would be willing to sit on the task force. She declined to join. Moore says the task force won’t bring Smith back, even though she recognizes the solutions need to center survivors such as herself. Mostly, she wants the state elected officials and CPD top brass to explain why they blamed Smith herself, rather than searching for her killer.

“They need to stop thinking that everyone is into prostitution and drugs,” she says. “I’m grieving but I’m looking for closure. . . . If it don’t ever rest, then I’ll take it to my grave.”

This piece was republished from the Chicago Reader.