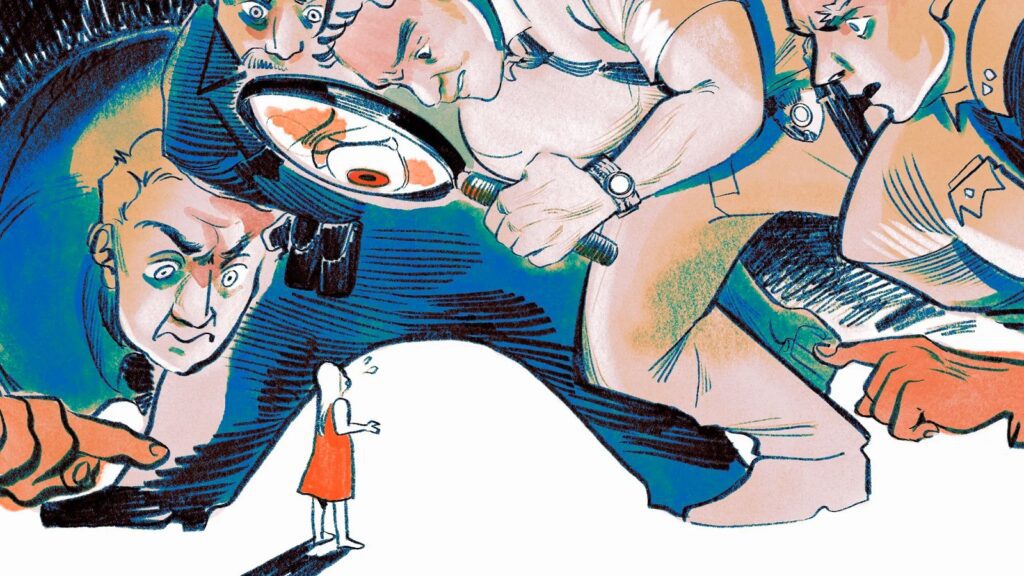

You’re Sexually Assaulted. You Report. And Police Make You the Suspect.

Police unleash a slew of interrogation techniques meant for criminal suspects on vulnerable people.

By Rachel De Leon

On September 26, 2023

This article is a collaboration between Mother Jones and Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit investigative newsroom.

Sequestered in a small interrogation room, sipping an iced coffee, Nicole Chase was trying to explain just how dysfunctional things had become at Nodine’s Smokehouse Deli and Restaurant, a family-owned place in Canton, Connecticut, that specialized in smokehouse meats and toxic masculinity.

There was the time one of her colleagues came to work high on acid, she said. On a day the restaurant made only $100, a manager closed early and got fired. Her boss, Calvin Nodine, was constantly telling sexist jokes and drinking on the job—even the customers saw it.

Chase thought she’d learned how to handle Nodine’s roving eyes and rude remarks. Until one night in May 2017, after his wife had gone home, when Chase said he pulled her into the men’s room, exposed himself, and ordered her to perform oral sex.

Chase reported the incident to police the next day, an awkward, abbreviated interview with a rookie officer in the main lobby of the station as her mother sat next to her. Chase decided to quit that day, and six weeks later, she’d almost given up hope that anything would happen when she was asked to meet with Detective John Colangelo, who was now taking over the case as the lead investigator. She’d never spoken to him before, but he was friendly in a professional way as he ushered her into the interrogation room, listening to her stream-of-consciousness recollections and jotting down contact info for people who might corroborate her story. Chase felt a glimmer of optimism: Maybe her now-ex-boss would face some accountability after all, she thought.

An hour into their videotaped interview, though, Colangelo’s tone and posture subtly shifted. Soon, he was chiding her for interrupting him and getting off-topic. “You know, no one comes and tells us the entire truth,” he told her. “No one.”

But there was one person in this conversation who was allowed to lie. Colangelo, as a police officer, had no obligation to tell the truth at all. He leaned into a common interrogation tactic known among law enforcement as a ruse or a bluff. Most would call it a lie.

He asked Chase what she’d say if he told her Nodine had already taken two polygraph tests. She was skeptical.

“I know he’s taken two polygraphs, and I know that there are issues in some of these stories,” he said.

In fact, police records showed Nodine had refused to take a police-administered polygraph. He told Colangelo that he paid for a privately administered test, but Colangelo never saw the results. Besides, Nodine admitted to Colangelo that he’d failed it.

Chase fell for the ruse, though, and just like that, her frenetic energy shifted to despair. It was true: There was something she hadn’t told police or her lawyer or her mother; she hadn’t told anyone.

She began frantically drumming her hands on her thighs, then burst into tears.

“As soon as he told me to do it, I just did it,” she blurted. “I just didn’t know what to do.”

Canton Police Department

“So you did give him oral sex,” Colangelo stated matter-of-factly. “Yes,” Chase sobbed. “Everything else is completely true.”

Now it all came flooding out: the humiliating details of what had happened between her and her boss in the bathroom, Chase’s history of abusive relationships, her embarrassment when people wondered why someone as smart and strong as she is would tolerate such abuse, her self-loathing that the pattern continued with Nodine and she’d given in to him without a fight. The 26-year-old mother had been afraid of losing her job, then worried that no one would understand, and now she was terrified that by not telling the complete story from the beginning, she’d wrecked her case.

But Colangelo did seem to understand. In his 25 years as an officer, he’d seen it all, he assured her. He offered to work with her to revise her written statement and asked if she was going to be OK when she left.

“I kind of want to thank you for making me do this,” Chase told the detective as she wiped her eyes.

“That’s what I’m here for,” Colangelo replied. “I’m here to serve everyone.”

In the weeks following the interview, Chase emailed Colangelo and went down to the station to revise her statement. But the detective had already done the last thing anyone in her situation would expect. He’d sent a warrant to the state’s attorney charging her with making a false statement and requesting her arrest.

By some estimates, more than half of women and nearly a third of men in the US will experience some form of sexual violence in their lifetimes. Most of those crimes go unreported. Of the cases that make it to law enforcement, the least likely outcome is the arrest of a perpetrator. The vast majority of complaints to law enforcement end with no trial, no conviction, and, for victims, no closure—instead, they leave with a deep mistrust of the legal system, while some predators go free and attack again.

But sometimes there’s another outcome: The victim becomes the suspect, charged with false reporting—even when the attack actually occurred. “Between the way that the police treated me and the assault itself, the police treatment has definitely hit me harder,” said Emma Mannion, who was charged with false reporting in Alabama in 2016. “Half of my nightmares are of the assault. And the other half is court.”

No one knows how often victims have been charged with falsely reporting a sexual assault. There’s been little effort by law enforcement authorities to document how many assault victims are wrongfully arrested or to understand the circumstances that lead victims to be accused of false reporting.

To understand the scope of the problem, I’ve spent the past five years digging into cases like Nicole Chase’s. I’ve found at least 230 cases in which alleged sexual assault victims were charged with a lying offense and these cases represent only the proverbial tip of the iceberg: A 12-year-old was charged with making up a rape by a family member, only to prove her innocence later when the same man raped her again—and she recorded the assault. I found college students interviewed without advocates or their parents, buckling under psychological manipulation from detectives and backtracking their statements. Megan Rondini, a 20-year-old University of Alabama student, accused a wealthy and connected businessman of rape in 2015 and quickly found herself under police suspicion. Tuscaloosa police turned the tables, investigating her for theft because she went through his car and took items she said she needed to get home. Seven months later, she killed herself. A grand jury had been tasked with deciding whether to indict Rondini on two theft charges, but she died before it voted. The jury ruled only on charges against the man she accused of rape—and did not indict him.

“You are confusing a person who is already traumatized and already has memory difficulties. This is not how you get information.”

I’ve also amassed a first-of-its-kind trove of audio and video evidence showing the main factors that can lead victims to be wrongfully accused, featured in “Victim/Suspect,” a documentary film by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting and Netflix. Police routinely unleash a slew of interrogation techniques meant for criminal suspects on unsuspecting young and vulnerable people. They told a young woman that surveillance footage (marked from the wrong day and time) disproved her entire account, confusing her and causing her to question her sanity. When an 18-year-old recounted to a detective how a man she accused of sexual assault grabbed her arm and tugged her away from a party, he used a flattery technique and commented that she was a “pretty young lady” and wondered who wouldn’t want to pull on her arm.

Both would go on to recant or backtrack on their claims, leading to false reporting charges.

My most startling discovery: Over and over again, it’s police who lie. And those lies can be used to gaslight and confuse reporting victims until they make inconsistent statements that undercut their credibility—and sometimes even make them recant. Of the 52 cases I analyzed closely, nearly two-thirds involved a recantation. In nine cases, the recantation was the only evidence cited by police in the records Reveal obtained.

People do sometimes lie about rape, just like any other crime: Criminal justice experts estimate that 2 percent to 8 percent of sex crime accusations are false. American history is replete with horrific examples. In the Jim Crow South, White people’s fabricated allegations of sexual assault were often the pretext for lynching Black men and terrorizing entire communities. In recent years, a few hyper-publicized incidents, like the 2014 Rolling Stone piece in which an anonymous source seemed to have made up her account about being repeatedly raped at a University of Virginia frat party, have stoked the belief—embraced by the men’s rights movement—that rape accusations are often made up.

Rape denialism runs alarmingly deep in the law enforcement community, too, for male and female officers. It’s common for police officers to overestimate the rate of false reporting of rape, even if they are assigned to work with victims of sex crimes. A 2010 study for the National Institute of Justice analyzed interviews with 49 detectives in different sex crime units and found that a majority of officers with limited or moderate experience (fewer than seven years) estimated that between 40 percent and 80 percent of all reports of rape were false. And a 2018 study published in Violence and Victims found that the more an officer believed in rape myths—the idea that women report rape after regrettable sex, for example, or that they bear responsibility if they were drunk—the higher they estimated the rate of false rape reports.

“If you think large numbers of people are lying,” says Lisa Avalos, an associate law professor at Louisiana State University who has spent a decade studying wrongful prosecutions of assault victims in the US and abroad, “your No. 1 approach to rape investigation is going to be, ‘Let me see if I can prove that she’s lying.’”

Sexual assault cases are inherently difficult to investigate, often plagued by a lack of corroborating evidence. “If you haven’t received really solid training and you don’t have a good professional support system to investigate the cases properly, what you’re thinking about is, ‘This is a case that’s taking my time…I need to clear it and get it off my plate as quickly as I can,’” Avalos says. “One of the ways that an officer can clear a sexual assault case is to decide the case is unfounded because the victim was actually lying.”

Police officers can be especially critical of acquaintance-rape cases, which make up an estimated 80 percent of sexual assaults. “The reality is that most victims actually know their assailants,” Avalos says, but among law enforcement, “there is sort of a blanket assumption…that if you know the guy, he can’t have raped you.” Often in such cases, she says the default police reaction is “to just assume the victim must be lying—’the victim must have some kind of vendetta against this individual.’”

That impulse is further fueled by a lack of trauma-informed training in how to interview victims of sex crimes. In recent decades, a large body of research has emerged showing the debilitating effects of sexual trauma on memory and behavior. Assault victims often can’t recall details of their attack, even in the immediate aftermath. They frequently omit important information—like the fact that they performed a sexual act because they were too afraid to fight back—out of embarrassment or shame or fear that they won’t be believed.

“It’s called avoidance behavior. We train on this all the time: ‘I’m gonna avoid talking about this part of the assault because it’s just too painful,’” says Tom Tremblay, a former police chief and former state public safety commissioner in Vermont who consults with police departments across the country on trauma-informed investigating. Avoidance is most common in settings “when the victim doesn’t feel physically, psychologically and emotionally safe,” Tremblay says.

Even something as basic as the way officers typically ask questions can be problematic, he says. “Police are trained to ask, ‘What happened? What happened next? What happened after that?’ ” That can force victims to relive a trauma before they’re ready, which can make them more confused—and seemingly unreliable. “We should not be demanding or expecting a chronological narrative for someone who’s experienced trauma.”

But many police officers don’t understand—or don’t take seriously—how trauma and stress can warp a victim’s memory and cognitive functioning. They view inconsistencies and omissions as evidence that a victim is dishonest. This is an error law enforcement makes again and again, Tremblay says. “We’ve misinterpreted trauma repeatedly and looked at it like it was deception.”

And because police officers don’t get much specialized training in talking to sex crime victims, they resort to techniques they do know how to use, including ruses and bluffs – methods designed specifically to interrogate suspects and obtain confessions, not to elicit a victim’s painful and truthful story. “It’s OK for police to present hypotheticals in an interrogation of a suspect of a crime,” Tremblay says. “That is not good police procedure to do that to a victim of a crime who’s experienced trauma.” A big part of a victim interview is to build trust, he says. “And you can’t build trust when you lie.”

The betrayal goes deeper, Avalos argues. “You are confusing a person who is already traumatized and already has memory difficulties. This is not how you get information.” In the context of a sexual assault, bluffing is “a really toxic thing to do to a victim,” Avalos says. “She’s wondering, ‘Am I crazy? Did I make this whole thing up?’ ”

Tremblay acknowledged that sexual assault cases are one of the most complex crimes to investigate. They can be hard to prove, and prosecutors tend to hold cases up to a standard of whether a jury would convict—even though the vast majority of criminal cases end in a plea agreement. But Tremblay says he is absolutely sure of one thing: Chase’s omission does not amount to a lie.

I first met Nicole Chase last year at her house in a small town in Connecticut, close to Hartford. It had been her grandmother’s house, where Chase and her mother both grew up. Now Chase owns it, sharing the cozy, spotless space with her fiancé, two kids, a cat and a bloodhound puppy. She’s down to earth, quick to admit when there’s legal jargon she can’t pronounce, but she tries anyway. She is surprisingly open and willing to talk about past traumas.

It had been five years since the ordeal with her former boss Calvin Nodine, and she felt like it was finally behind her. “I’m hoping that this is the end of the cycle of all the bad,” she says.

For Chase, the cycle of bad started early. Her father was addicted to crack cocaine, she has reported, and she was using it too by the time she was 11 or 12. Before long, she was addicted, eventually spending a year in rehab. In her 20s, she was involved with a man who she says abused her physically and emotionally. By the time she found the Nodine’s job, “I had no savings. I didn’t even have a bank account…I had not a pot to piss in.” Eager to impress her new employer, Chase threw herself into her job, doing a little bit of everything—ringing up orders, cleaning, preparing food. Her mother sometimes worked at the restaurant, too.

Nodine was 30 years older and far more affluent, though in blue jeans and suspenders, he gave off a casual country vibe, much like the decor of his restaurant. Nodine’s Smokehouse, founded by his late father in the 1960s, produced high-quality Connecticut-made hams, bacon, and sausages for sale in grocery stores around the country. The restaurant opened in 2016. He liked to tell dirty jokes, and his female employees were often the target. Chase’s younger colleague Allie Archer told me Chase was singled out. One of Nodine’s favorite jokes was about blondes being like butter, “easy to spread.” Chase, who was the only blonde working there, says she brushed him off and just kept working.

Google Street View

After a promising opening, the restaurant began to struggle, and Nodine started attracting the wrong kind of attention. “Very inconsistent,” a Yelp review from April 2017 reads. “Owner can be seen randomly wandering in his socks with beer in hand.” In May 2017, Nodine’s stepson—the head chef and general manager—quit abruptly, and the staff turmoil deepened.

The bathroom incident occurred a few days later, during this chaotic period. Earlier that day, a visibly inebriated Nodine told one of his trademark dirty jokes, this time going so far as to grope Chase’s butt as Archer watched. “I wish I had actually said something to him,” Archer said. “I wish I’d slapped him, honestly.”

At some point that same day, Nodine informed Chase she was getting a promotion—she would be the new manager. Later that night, her ride home already waiting for her in the parking lot, she encountered Nodine standing alone in the hallway. Chase said he hugged her and told her that they were going to get through this hard time. Then, according to Chase, he pulled her into the men’s room, shut the door behind them, and demanded oral sex.

That was as much as Chase felt safe telling a young officer named Adam Gompper in a recorded interview the next day in the lobby of the Canton Police Department. She’d brought along her mother for support. She left out the worst parts of it all—how Nodine had pushed her head down toward his exposed genitals and that out of fear, she gave him oral sex.

Gompper never asked whether she complied, and he said he didn’t think the incident sounded like a sexual assault. But he agreed that Nodine’s actions were inappropriate and said Chase could make a formal report when and if she was ready.

Canton Police Department

In the meantime, he suggested that she confront Nodine and tell him to leave her alone. Gompper added that he hoped things worked out for her. “But it sounds like he’s never going to change,” he told her.

Chase returned to the restaurant later that day. She hoped Nodine had been so drunk that he wouldn’t remember what happened. Maybe he’d even apologize. Instead, he summoned her to help clean his small, closet-like office. She declined.

“Can you think of something else better to do than fuck me?” he asked, according to Chase.

Chase worked the rest of her shift, enlisting two male co-workers to stay near her so she wouldn’t be alone with her boss. At the end of the day, she grabbed a photo of her daughter that she kept at work, walked out the door, and never went back.

A few days later, she and Archer went to the police station to give written statements. But once again, Chase couldn’t bring herself to disclose everything that had happened in the bathroom. She thought she didn’t need to.

“I just figured that I was going to say as much as I was comfortable saying and that he’d be held accountable for something or just even get a restraining order,” Chase told me. “And I’d go on my merry way.”

Calvin Nodine declined to be interviewed. Detective John Colangelo’s attorney said in an emailed statement that Colangelo “acted appropriately at all times,” and that she advised Colangelo not to speak with me. But I obtained a police interview between Nodine and Colangelo that occurred a few weeks after the incident, and what’s most striking about it is how differently the police detective handled major changes in Nodine’s story. Colangelo didn’t just ignore the inconsistencies; he gave Nodine and his lawyer a strategy for how to explain them away and even turn Chase from the accuser into the suspect.

The recorded meeting took place in the same claustrophobic room as Chase’s interview, but with four people in attendance—Officer Adam Gompper and Nodine’s lawyer were also there.

“If the police don’t believe you, they might prosecute you.”

Colangelo, now the lead detective, does most of the talking. In classic TV cop-show fashion, he started off chummy and casual, chit-chatting about golf before introducing the issue at hand.

“You got employees in an uproar or something…What’s this girl’s name? Nicole?” Colangelo asks, sounding disgruntled. “What’s Nicole’s deal?”

The detective notes that Chase’s complaint alleged inappropriate talk and “sexual stuff.” He hadn’t questioned Chase yet, but he makes it clear that he already has his doubts.

“Let me put it this way: I’m not so sure I believe everything she’s telling me,” Colangelo says.

In the video, Nodine appears uncomfortable, his legs crossed and twisting away from his slumped shoulders. He acknowledges that he uses crude language sometimes—“I’m a meat guy, I grew up in meat plants,” Nodine says—but he insists nothing happened that night, or ever, with Chase.

Colangelo tells him he’s got conflicting accounts—from Chase and another employee. He offers Nodine another scenario. “If you were fooling around with (Chase) consensually, that’s a whole different story.”

Before Nodine can respond, his attorney cuts him off. He asks to speak with his client alone.

A few minutes later, Nodine comes back with a new story: In this telling, something did happen, but it was Chase who was the aggressor. Now, Nodine claims she grabbed him in the dark hallway and told him that she needed to show him something in the men’s room. Then she pulled down his pants and performed oral sex.

“So you think she’s a liar?” Colangelo asks.

“As far as it not being consensual? Absolutely,” Nodine replies.

Nodine’s old and new stories clearly conflicted. At least one of them had to be a lie.

At this point, according to sexual assault experts who’ve seen the video, Colangelo had the advantage. If his goal was to prove or disprove the case against Nodine, he should have started asking detail-oriented questions to confirm Chase’s statement or expose inconsistencies in Nodine’s story: How long were you in the bathroom? How much did you have to drink? Did you lock the door or did she? Where were your hands while this was taking place?

Instead, Colangelo suggests that Nodine take a polygraph. If he passes, the detective says he’ll have the leverage to ask Chase to take a polygraph, too. He tells Nodine he’s done this before with another woman he suspected of lying.

“So you switch the case,” Colangelo explains. “That’s all.”

As for Nodine’s initial lie that nothing had happened, Colangelo shrugs it off with a sports analogy, telling Nodine he’ll give him “a bit of a base on balls on the first false statement.”

Even Nodine’s claim later that he failed a private lie detector test—he blamed medication he forgot to take—didn’t prompt Colangelo to interview any of the people Chase named or to take any other steps to corroborate her story.

Despite the inconsistencies in Nodine’s story, Colangelo chose to lie to Chase about the polygraph and use the omissions in her own story to charge her with giving a false statement to a law enforcement officer, a misdemeanor. In early September 2017, four months after making her initial report, Chase found herself back at the police station, where she was fingerprinted and her mugshot taken. If convicted, she faced a fine of $2,000 and up to a year in jail.

In numerous ways, Nicole Chase is typical of the victims-turned-suspects in my analysis. Nearly all were women; most were under 30 when arrested. More than two-thirds knew their alleged assailant; few put up any physical resistance to their assailant or suffered visible injuries.

“There are many women of color today who don’t believe that the police are going to help them, and so they don’t even go to begin with.”

The victims charged with false reporting in my analysis were usually White. Even though Black and Brown people experience sexual violence at higher rates, they are less likely to report their assaults due to historical mistreatment by police, law professor Lisa Avalos says. “There are many women of color today who don’t believe that the police are going to help them, and so they don’t even go to begin with.”

Still from “Victim/Suspect,” courtesy of Netflix

And as in Chase’s case, I found others in which the central evidence supporting a false reporting arrest was derived from police bluffs or ruses. Sometimes police told a lie to manipulate a reluctant victim into coming to the station for arrest. In a 2018 case, a law student in Kansas was asked to come to the station to help police decipher an anonymous letter connected to her report that a colleague had raped her. But when she arrived, the detective admitted there was no letter. “I got you here under, basically, a ruse,” he said in their recorded interview.

Instead, he had a warrant for her arrest. A short while later, she left in handcuffs on her way to jail. She was charged with three counts of false reporting—one for each time she said she was raped. The prosecutor’s office later dismissed the charges, saying it believed in the “merits” of the case but didn’t want to discourage other survivors from reporting their attacks.

In three instances, investigators lied about supposedly damning video evidence that they claimed contradicted the victims’ stories. After 18-year-old freshman Nikki Yovino reported being raped by two men at a college party in Connecticut in 2016, a detective told her there was cellphone video of the entire sexual act, proving that she wasn’t assaulted. Faced with such “proof,” she recounted to me, “I told him what he wanted to hear just so he can leave me alone.” He asked repetitive questions, and when he didn’t like her first, second, or third answers to the same question, she backed down, edited her statements, and eventually agreed when police insisted the encounter was consensual. But the police claim about the video was a lie; investigators had only an eight-second video that offered no insight about whether Yovino consented. After a year of fighting the charges and on the verge of trial, Yovino pleaded guilty to two counts of second-degree falsely reporting an incident and one count of interfering with police. She was sentenced to a year behind bars and three more on probation.

The detective told her that surveillance evidence contradicted her story, that she was caught making out with the man she accused and went willingly into his car. She was lying, he said, and taking time away from his “true” victims. She apologized and was arrested that day. But she never saw the footage. Her mental health was rapidly declining and she was fearful that she might not survive a trial, so she pleaded guilty to a youthful offender charge—a catchall used for young people so they can keep records sealed. She never saw any surveillance footage until Reveal sued in 2020 to obtain it. There were no cameras recording the parking lot where she said she was raped. The only footage of Mannion showed a brief kiss while walking with the suspect, which she’d already told police about.

Still from “Victim/Suspect,” courtesy of Netflix

Dyanie Bermeo was 21 in 2020 when she told deputies in Washington County, Virginia, that a police officer or someone impersonating one had pulled her over and groped her. Officers doubted her account and told her they found surveillance footage proving that no one pulled her over. She never saw the footage – which was dark, grainy, and labeled with the wrong date and time—before they interrogated her. So when they asked if the stop really happened, she said it didn’t; Bermeo told me it was because she was tired of trying to prove herself and wanted the interrogation to end. A judge later vindicated her by finding her not guilty of the false reporting charge on appeal.

In nearly all the cases in my data sample, the alleged victims-turned-suspects were charged with misdemeanors, which carry lower sentences than felonies. Still, law enforcement’s zeal to punish their alleged lies was sometimes evident in the creativity of the charges. In Yovino’s false reporting case in Connecticut, prosecutors used her rape kit to tack on an extra felony charge, arguing that she “used her own vaginal secretions, which were indicative of recent intercourse, to mislead the nurse and law enforcement,” according to court records.

More routinely, law enforcement agencies promote the arrests, creating the conditions for public shaming. “It’s as though police are proud,” Avalos says. “They’re telling the community, ‘We have identified a false reporter of sexual assault, and her name is Jane Doe.’ ” In many of the cases I examined, alleged victims saw their full names, mugshots, and horrific details of their alleged assaults published in newspapers or on police social media accounts—often without their knowledge, much less their consent—triggering a cascade of online harassment and vicious slurs. Some cases became national news, stoked by media reports and men’s rights groups. Women were told by online commenters that they should get longer prison sentences or that they weren’t attractive enough to have been assaulted.

Still from “Victim/Suspect,” courtesy of Netflix

Public shaming doesn’t just compound the trauma of being sexually assaulted and then not being believed. In the internet era, the injuries—social, legal, mental, moral—are life-altering and almost impossible to overcome. Many of the women in my investigation cut short their schooling, left jobs, and moved to places where their cases weren’t known, but their efforts were often futile. Mannion tried to rebuild her life after her arrest, leaving the University of Alabama and moving back home to New Hampshire. She applied for several open positions to teach dance and got a call back for one. Mannion arrived expecting an interview. Instead, the hiring manager said she had Googled her and called her foolish for thinking the studio would ever hire a “criminal.”

“The whole thing felt unnecessarily malicious,” Mannion recalls.

The consequences for false reporting prosecutions are devastating not just for wrongly accused victims, but also for the criminal justice system and the safety of entire communities. “They are chilling the reporting of sexual assault because other victims are going to be afraid to come forward,” Lisa Avalos says. “The message that they send to all the sexual assault survivors in their community is that if the police don’t believe you, they might prosecute you.”

I’ve seen how this plays out firsthand. During my investigation, a former roommate of one of the prosecuted women in my database confided that she, too, had been sexually assaulted, not long after her roommate’s attack. She was worried she might get the same treatment from police if she came forward. So she never did.

Yet instead of taking steps to protect sex crime victims from being wrongfully accused, at least four state legislatures – Alabama, Kentucky, New Jersey, and Missouri—have introduced bills in recent years aimed at making false reporting a more serious crime. Montana passed such a law in 2021. A few other bills would open the door to bring civil lawsuits against a person who makes an alleged false report. West Virginia, and Illinois introduced bills in 2021 that were so broad that a person who was simply questioned by police could sue for being falsely accused. The Illinois proposal specified that the claim could go forward even if the other person was acquitted of filing a false report. Neither bill passed.

Bills in at least eight states have targeted false reports motivated by bias, which is intended to deter people from calling law enforcement on people of color or other vulnerable groups of people. But the increased penalties could inadvertently affect sexual assault victims. Another spate of bills designed to stop “swatting,” or reporting a fake emergency, could ensnare some sexual assault reports. But at least one proposal was squarely aimed at people reporting rape: One lawmaker in Alabama—where Emma Mannion and Megan Rondini were both charged—tried in 2019 to upgrade the penalty for false reports of rape and sexual assault from a misdemeanor to a class C felony, punishable by up to 10 years in prison. The bill died in committee.

A far better approach, Avalos says, would be to ban the use of bluffs and ruses against people who’ve reported a sexual assault.

Additionally, if police want to press charges against a reporting victim, prosecutors should use their discretion to determine whether criminal charges are the best course of action to promote public safety, according to the organization End Violence Against Women International, a nonprofit that teaches trauma-informed law enforcement responses.

One of the organization’s training bulletins points out that prosecutors have an ethical obligation to balance their duty to enforce the law with the public’s interest. “They are not required to file charges just because they have the evidence to do so,” it says.

In a case like Nicole Chase’s, it was the state attorney who signed the warrant, leading to her arrest.

Police must also change their attitudes about sexual assault allegations, says police consultant Tom Tremblay—instead of automatic skepticism, they should begin every investigation by assuming the attack happened. Tremblay didn’t come up with this idea; End Violence Against Women International has built an entire training campaign around the idea that police should “Start by Believing.” But he’s a big fan, in part because he thinks it helps police do a better job of getting to the truth of what happened and solving a case. Skepticism or doubt signals to a victim that reporting the crime was the wrong course of action and is likely to make her shut down, he says – or in a worst-case scenario, falsely recant just to get away from police. If a victim feels they’re being helped, they’re more likely to participate in the investigation, providing better details, evidence, and leads to follow, Tremblay says.

It prompted a change to Canton police policy: If an officer decides to go after a reporting victim, a supervisor now must review the case first.

Trauma-informed training for police is also critically important, he says. This involves everything from understanding how trauma affects memory to knowing how to question victims and understanding that just because victims leave out major details from their initial accounts doesn’t mean they’re lying.

When Chase revealed that she had complied with Calvin Nodine’s demands, Tremblay said he would have asked what he summarizes as “thinking, feeling, and experiencing” questions: “We’re gonna support you in this process, but help us understand your thought process when you said this. Help us understand what you were experiencing when you said this. Help us understand what you might have been feeling when you left this information out.” Chase would have had the chance to explain what she told me: that she was scared, worried what Nodine would do if she denied him, and feeling like she had left her own body. A trauma-informed detective would recognize that this sounded like disassociation—a common psychological response for victims of sexual violence.

But police departments have to improve many other aspects of sex crime investigations, too. Avalos wants to see new requirements that would place the burden on police to prove elements of the case before resorting to false reporting charges. First, Avalos argues, a thorough investigation of the sexual assault is a necessity. Officers should interview key witnesses, review lab results and give the victim time to rest and recover memories, for example. After that investigation, if charges are pursued, there should be evidence that no sexual assault occurred or was attempted—and not be based solely on a recantation. Avalos says it’s also necessary that police not rely on rape myths or trauma responses to conclude that the victim lied.

There is one important way that Nicole Chase’s case stands out from many others in my five-year investigation. She used the legal system to fight back. Her criminal case was dropped a month after her initial court appearance, and she decided to sue everyone. Her lawyer filed a civil suit against the city of Canton, the police department, Detective John Colangelo, Officer Adam Gompper, and Calvin Nodine, which in turn triggered an internal affairs investigation of Colangelo’s conduct in the case.

Colangelo was suspended for three days without pay for his actions. He then sued the police chief and the city in 2021 for a “sham” investigation to “appease the #metoo movement,” according to court records, but a judge dismissed his claim. He retired that same year and is now the head of security at a local nonprofit. After a series of disciplinary incidents unrelated to Chase’s case, Gompper also resigned and now works as a police dispatcher for a nearby department. He did not respond to requests for comment.

Nodine denied ever having sexually assaulted or harassed Chase and was never criminally charged, but he agreed to settle for an undisclosed amount. His restaurant closed in 2019. The city fought the lawsuit for years, including an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, but finally settled with Chase for $800,000 last year.

For Chase and her lawyers, the victory wasn’t just about money. The lawsuit also set an important legal precedent, as federal District Judge Vanessa L. Bryant ruled that victims have no obligation to report their assaults or to include every painful detail.

And it prompted a change to Canton police policy: If an officer decides to go after a reporting victim, a supervisor now must review the case first.

These days, Chase is no longer working on anyone’s schedule but her own. She’s not on her feet all day. She decorates epoxy tumblers and sells them on Facebook, when time allows. She’s home for her kids after school, makes dinner for them and her fiancé, and takes care of the dog and cat, in the childhood home they were able to buy due to the settlement money.

She still deals with vivid nightmares about Nodine and the police and anxiety that prevents her from driving. But life is peaceful, stable, comfortable, and maybe even predictable most days – a far cry from the chaos of before. The string of trauma from her father, her ex, Nodine, and the police – she says she is ready to put it all behind her.

“I pray that there’s no more,” Chase says. “I’m hoping that is the last thing that comes to me in this life in the form of men.”

This piece was republished from Mother Jones.