4 Reasons We Should Worry About Missing Crime Data

By Weihua Li and Jasmyne Ricard

On July 13, 2023

The FBI’s crime data is still incomplete — and politicians are taking advantage.

For more than 100 years, the FBI has been collecting crime data from local police departments across the country through the Uniform Crime Reporting Program, which has been the gold standard of national crime statistics.

By 2020, almost every law enforcement agency was included in the FBI’s database. Some agencies reported topline numbers, such as the total number of murders or car thefts, through the Summary Reporting System. Others reported granular incident data with details about each reported crime through the newer National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS).

Then it all changed in 2021. In an effort to fully modernize the system, the FBI stopped taking data from the old summary system and only accepted data through the new system. Thousands of police agencies fell through the cracks because they didn’t catch up with the changes on time.

The Marshall Project is tracking police agency participation using data obtained from the FBI. Here are four takeaways from our analysis.

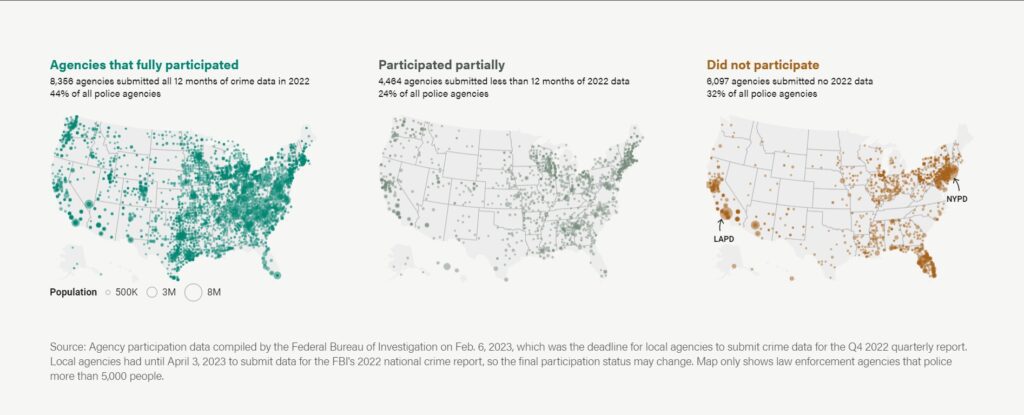

Participation in the FBI’s database improved slightly, with about two-thirds of law enforcement agencies now included.

More than 6,000 law enforcement agencies were missing from the FBI’s national crime data last year, representing nearly one-third of the nation’s 18,000 police agencies. This means a quarter of the U.S. population wasn’t represented in the federal crime data last year, according to The Marshall Project’s analysis.

The old summary-level data reporting system, retired in 2021, was also revived last year when the FBI announced that it would accept data through it again. It’s unclear how many police agencies took advantage of the opportunity because the participation data is not available yet. But many states, like Illinois, had already planned to phase out the old system.

Reporting has increased compared with 2021, the first year the FBI changed the collection system, with 2,000 more police agencies submitting their 2022 crime records. But the data gap still creates significant challenges for scholars and policymakers to make sense of crime trends.

Many of the largest police departments, like the NYPD and LAPD, are still missing.

Some large police departments began to report data to the FBI again in 2022, like the Miami-Dade Police Department. But the two largest police agencies in the U.S., the New York Police Department and the Los Angeles Police Department, are still missing in the federal data.

A spokesperson from the LAPD said the department submitted crime data to the California Department of Justice using the old data collections system, but is still working on complying with the FBI’s new record standards. “The intent is to have it implemented by January 1, 2024 as part of the rollout of the new [Record Management] system,” the spokesperson said.

An NYPD spokesperson said the department is currently collecting crime data in compliance with the new system. “We anticipate that the agency will be NIBRS-certified in the very near future,” the spokesperson said, but didn’t offer a specific timeline.

Many large police agencies still missing from national crime data

Of the 19 biggest law enforcement agencies — each of which police more than 1 million people — seven were missing from the FBI’s 2022 crime data. The missing agencies include the LAPD, the NYPD, and police departments in Phoenix, San Jose and New York’s Suffolk County.

| Agency | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| New York Police Department, N.Y. | No reporting | No reporting |

| Los Angeles Police Department, Calif. | No reporting | No reporting |

| Chicago Police Department, Ill. | Reported 7 months | Full reporting |

| Houston Police Department, Texas | Full reporting | Full reporting |

| Harris County Sheriff’s Office, Texas | Full reporting | Full reporting |

| Phoenix Police Department, Ariz. | Reported 1 month | No reporting |

| Las Vegas Metro Police Department, Nev. | Full reporting | Full reporting |

| Philadelphia Police Department, Pa. | Reported 9 months | Full reporting |

| San Antonio Police Department, Texas | Full reporting | Full reporting |

| San Diego Police Department, Calif. | Full reporting | Full reporting |

| Dallas Police Department, Texas | Full reporting | Full reporting |

| Suffolk County Police Department, N.Y. | No reporting | No reporting |

| Miami-Dade County Police Department, Fla. | No reporting | Full reporting |

| Fairfax County Police Department, Va. | Reported 11 months | Full reporting |

| Nassau County Police Department, N.Y. | No reporting | No reporting |

| Montgomery County Police Department, Md. | Full reporting | Reported 2 months |

| San Jose Police Department, Calif. | No reporting | No reporting |

| Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office, Fla. | No reporting | No reporting |

| Austin Police Department, Texas | Full reporting | Full reporting |

Less than 10% of agencies in Florida and Pennsylvania are available in the national crime data, but many states have near-perfect submission rates.

Most police agencies do not submit data directly to the FBI. Instead, a police agency usually submits crime data to the state’s law enforcement department, which acts as a data clearinghouse. The state agency then submits data from all the agencies to the FBI.

In 2021, California and Florida were the only two states that were not certified with the FBI’s new data collection system on time, which meant neither state could submit any data at all by the FBI’s deadline. Starting in 2022, both states were certified to submit crime data through the FBI’s new system.

After both states began submitting data, nearly 400 California police agencies were included in the FBI’s crime data last year, which represents half of the state’s agencies. This was a significant jump from 2021, when only a handful of agencies in California that directly submitted their records to the FBI were in the federal database.

Florida and Pennsylvania lag behind in FBI crime data participation

Two years after the FBI switched methods for collecting crime data, many law enforcement agencies across the country have adapted, with nearly perfect participation rates from 17 states and the District of Columbia. The biggest exception is Florida, where less than 8% of agencies are represented in the 2022 data. Pennsylvania lags behind too, with less than 10% of agencies included.

In Florida, however, only 49 of the state’s more than 500 agencies submitted data to the FBI last year, representing less than 8% of the state’s police departments. Some of the largest agencies, like the Miami Police Department, the Pinellas County Sheriff’s Office, and the St. Petersburg Police Department, are missing from the national context.

While Florida agencies had the lowest participation rate in the federal crime data, Pennsylvania is a close second, with more than 90% of the state’s police agencies missing.

That’s followed by New York State, where three-quarters of the agencies were missing from the federal database. That includes the three police agencies in the state that had more than 1 million people in their jurisdiction: New York Police Department, the Suffolk County Police Department, and the Nassau County Police Department.

On the other hand, 17 states were ahead of the curve and had nearly perfect participation in the FBI’s crime data.

The patchy crime data has real consequences.

Over the last year, the patchy national crime statistics have led to confusion and uncertainty.

When the FBI released its 2021 national crime data last fall, it couldn’t say if crime went up, went down, or stayed the same. The FBI concluded that all three scenarios could be possible because of the gaps in the data collection.

The data issues affected hate crime statistics as well. When the FBI first unveiled the hate crime numbers, it looked like they had dropped significantly. But the report missed hate crimes from nearly 40% of law enforcement agencies in the country, and the agency faced outcry from experts and policymakers who said the numbers were “worse than meaningless.”

The FBI later went back to more than 7,000 police departments that didn’t supply hate crime data, and asked them to submit their numbers through the old data collection system that was supposed to be retired. When the FBI released a new hate crime report this spring with more data, it showed a nearly 12% increase in hate crimes from 2020 to 2021.

In June, when Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis announced his presidential campaign, he bragged about Florida’s crime rate hitting a 50-year low in 2021. But his statement relied on incomplete data — more than 40% of the state’s population was missing from Florida’s state-level crime data in 2021, as many police departments were transitioning their record management system to the FBI’s new standards.

In Wichita, the incumbent Mayor, Brandon Whipple, used faulty crime statistics in his bid for re-election earlier this summer. Using data from the FBI’s Crime Data Explorer, Whipple claimed that violent crime had been reduced by half during his administration. But the reality was the FBI’s data missed half of the violent crime that the Wichita Police Department recorded, a confusion caused by the police department’s attempt to transition its crime data reporting system, the Wichita Eagle first reported.

As many police departments are still in the process of complying with the FBI’s new reporting requirements, experts predict that the national crime data is likely to be incomplete for years to come, and will leave more room to politicize crime statistics without concrete evidence. These issues are likely to become more urgent as the country moves closer to another election cycle where crime is certain to be a potent issue: In 2024, the FBI is likely to release its national crime data just before the election.

“People will use crime data to say whatever they want,” said Jeff Asher, a criminologist and co-founder of AH Datalytics. “When you don’t have that certainty of having nearly every agency reporting data, it means that you need a lot of literacy to be able to combat items that are being stated in bad faith.”

This piece was republished from The Marshall Project.