Patrol dogs are terrorizing and mauling prisoners inside the United States

By Hannah Beckler

On July 23, 2023

In a photo taken in December 2003, two US military dog handlers, Sgts. Santos Cardona and Michael Smith, corner a detainee at Abu Ghraib, the prison in Iraq used by the US-led coalition and the Iraqi government. Smith holds back his unmuzzled dog Marco, a large black shepherd who lunges against his lead. Cardona’s Belgian Malinois is in a low, predatory crouch. Mohammed Bollendia, the detainee, has been stripped naked. He cowers against the cell-block wall, his arms pulled protectively over his head. His face is twisted in terror.

In another photo, Smith holds Marco back as the dog bares his teeth inches away from another detainee, this one in an orange jumpsuit. The detainee, later identified as Ashraf Abdullah Ahsy, is on his knees, and his arms appear to be cuffed behind his back. His eyes are huge with dread.

A US soldier named Ivan L. Frederick II later testified that Cardona told him he and Smith made a game out of using their dogs to frighten Abu Ghraib detainees until they urinated or defecated.

An Abu Ghraib interrogator, Sgt. John Ketzer, testified that he saw Smith command Marco to bark within a foot of two terrified teenagers inside a prison cell. The younger, smaller boy tried to hide behind the other. “The kids were screaming,” Ketzer said.

The human-rights abuses committed by US soldiers at Abu Ghraib, including the use of dogs to attack and terrify detainees, sparked international condemnation and outrage. Smith and Cardona were ultimately court-martialed and found guilty on a variety of charges including, for Cardona, aggravated assault and, for Smith, maltreatment of prisoners.

Associated Press

In May 2004, then Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld addressed Congress. The abuse of detainees at Abu Ghraib “was inconsistent with the values of our nation,” Rumsfeld said. “It was certainly fundamentally un-American.”

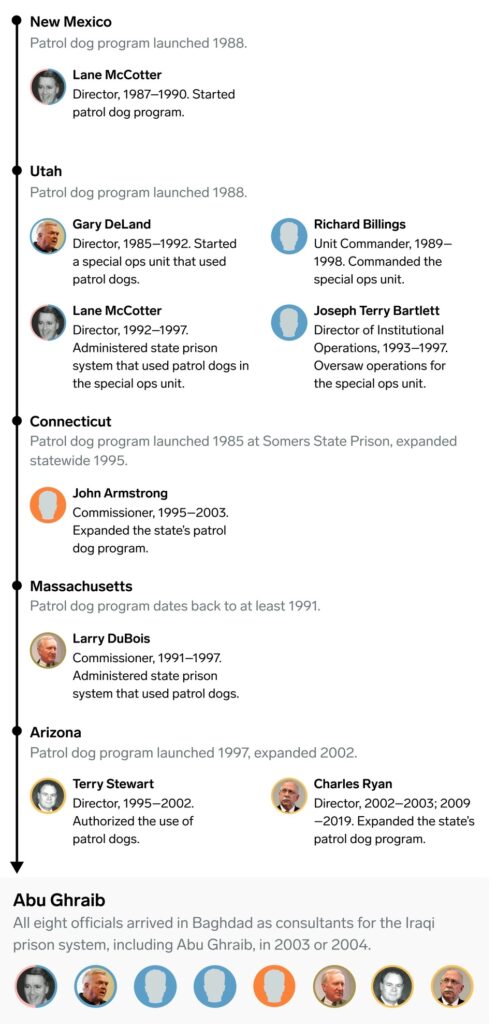

Yet the use of attack-trained dogs at Abu Ghraib appears to have been imported from the United States. A 2005 report from the Department of Justice’s inspector general scrutinized the private contractors who helped to build and run Abu Ghraib, detailing the backgrounds of the eight corrections experts who selected the site, oversaw the rebuilding of the prison, and trained staff at Abu Ghraib: Lane McCotter, Gary DeLand, Terry Bartlett, Richard Billings, Larry DuBois, John Armstrong, Terry Stewart, and Charles Ryan. Each had been a high-level state prison administrator or corrections commissioner before arriving in Baghdad.

All eight, Insider has found, previously started, expanded, or administered programs at US prisons that authorized the use of dogs to attack and intimidate incarcerated people. McCotter in New Mexico and Utah; DeLand, Billings, and Bartlett in Utah; Ryan and Stewart in Arizona; DuBois in Massachusetts; and Armstrong in Connecticut.

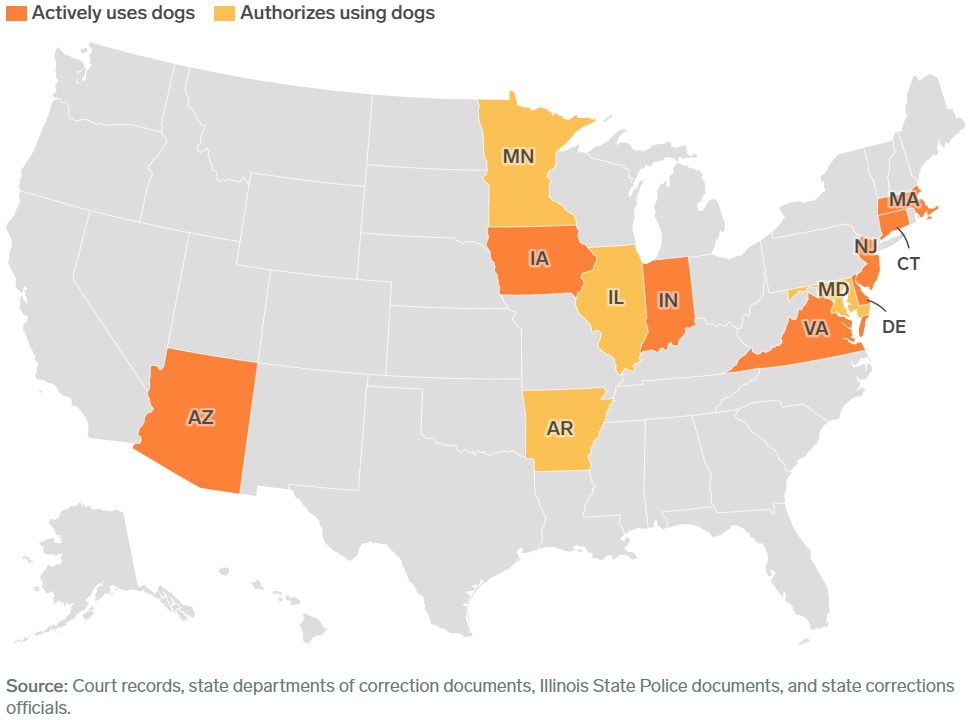

Two decades after the human-rights abuses unfolded at Abu Ghraib, almost all of these state prison systems continue to use unmuzzled attack-trained dogs. Insider has identified 12 states that authorize their use against people in state custody. At least 23 prisons in eight states have deployed attack-trained dogs on prisoners in recent years — Arizona, Connecticut, Delaware, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Virginia. Over the past six years, hundreds of incarcerated people have been bitten or mauled.

Human Rights Watch researchers wrote, in 2006, that they were unaware of a single other prison system in the world that used dogs to attack people in the confined space of a cell.

The path to Abu Ghraib

A Department of Justice report named the private contractors hired by the United States as correctional consultants in Iraq. All eight were previously associated with patrol dog programs in US prisons.

Alexandria, Virginia

When Adrian Duran was 10 years old, a neighbor at the end of his cul-de-sac in Alexandria, Virginia, gave him a black pit-bull puppy. He cradled him, squirming and warm, under his shirt and carried him home, smuggling him through the back door of his mother’s house and down the stairs into the basement where he planned to keep him hidden in the laundry room.

His mother discovered the puppy shortly after and, furious, told Duran he’d have to sleep with the dog in the basement. So Duran curled up on a pile of blankets on the floor and held the puppy’s soft, solid weight on his chest as he fell asleep each night. He called him Blackie.

Courtesy of Adrian Duran

Every day after school, Duran would run home, bolt down the basement stairs, and open the door to the laundry room where Blackie waited for him, yipping in excitement. His mother worked late, so Duran would take Blackie into the streets with him, visiting friends and neighbors and meeting up with older kids in backyards and garages, and on street corners. He tied his blue bandana around the puppy’s neck.

Blackie grew into a large, heavily muscled pit bull. When Duran was threatened by other kids, Blackie squared off by his side and growled. Duran bought Blackie a spiked collar and took him everywhere; Blackie became Duran’s protector and his most devoted friend.

At around 14, Duran started hustling. He joined a gang and started stealing — first small things, then cars. His mother told Duran that if he got arrested, she would be forced to put Blackie out in the street. Duran loved his dog too much to face that risk. Gutted, he left Blackie with a neighbor who promised to care for him.

Months later, Duran was arrested for driving a stolen car across state lines. In 2008, he pleaded guilty to an assault and got 15 years. By age 18, he’d been transferred to Sussex I State Prison.

There, his relationship to dogs shifted. It felt as if patrol dogs were everywhere, barking and snarling, lunging on their leads just feet away as the men walked between prison buildings. He couldn’t escape them. Their near-constant barking echoed and amplified against the concrete and steel of his cell. At 19, he saw one attack a man for the first time. The man’s screams nearly obliterated his memories of Blackie.

Duran witnessed 10 more vicious attacks over the next 10 years, experiences so terrifying that he structured his days to avoid the dogs at all costs.

Then he was brutally attacked himself.

The Virginia Department of Corrections

Police departments have long employed trained attack dogs to supplement the range and speed of officers in the field. But prison patrol dogs aren’t deployed for chases; they are used inside the prison walls. In these tight, enclosed spaces, the aggressive barking and threat of attack terrorize people trapped inside razor-wire fences and cell doors. The use of dogs to attack people in the confined space of a prison cell has been described by Human Rights Watch as a “well-kept secret” — and a human-rights violation. The dogs’ presence inside prisons, the organization found, “is intended to terrify and intimidate.”

Even witnessing a dog attack in close quarters is harrowing. One former Virginia corrections officer said watching a dog attack a person, hearing their screams and desperate pleas and seeing all that blood, was a “primal” experience and deeply traumatizing. “It’s just not something you forget,” he said.

For those who are the intended target of the intimidation, witnessing a dog attack is devastating, multiple men told Insider. Many suffer nightmares, intrusive thoughts, and fear for weeks and months after seeing an attack. For the hundreds of men who are bitten or mauled themselves, the physical and emotional impact can last for years.

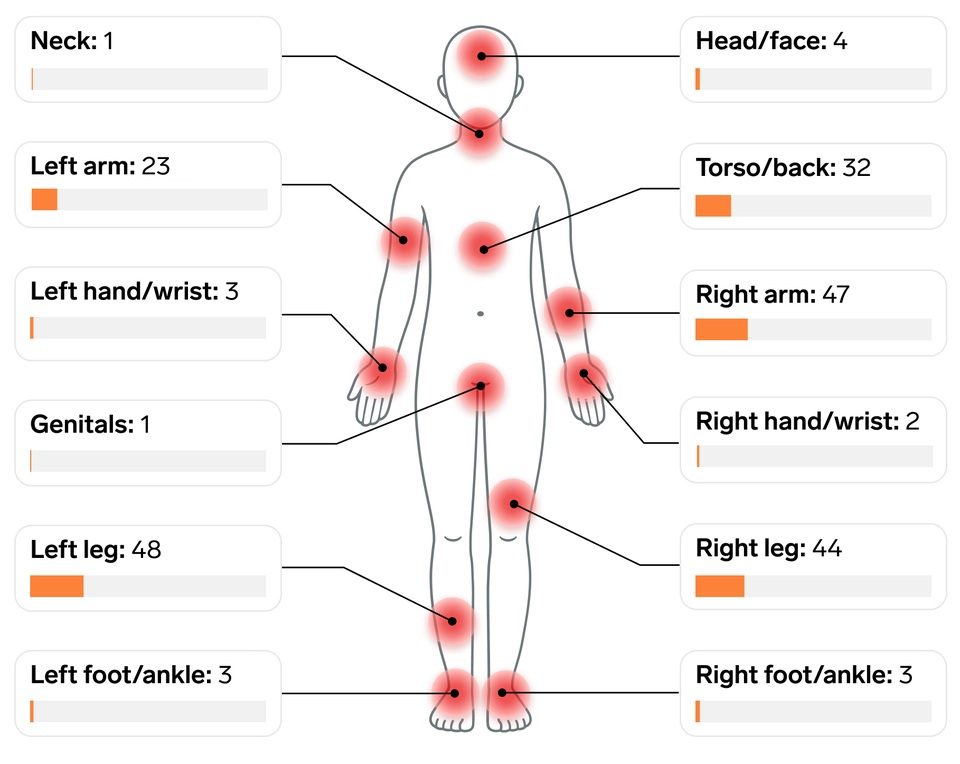

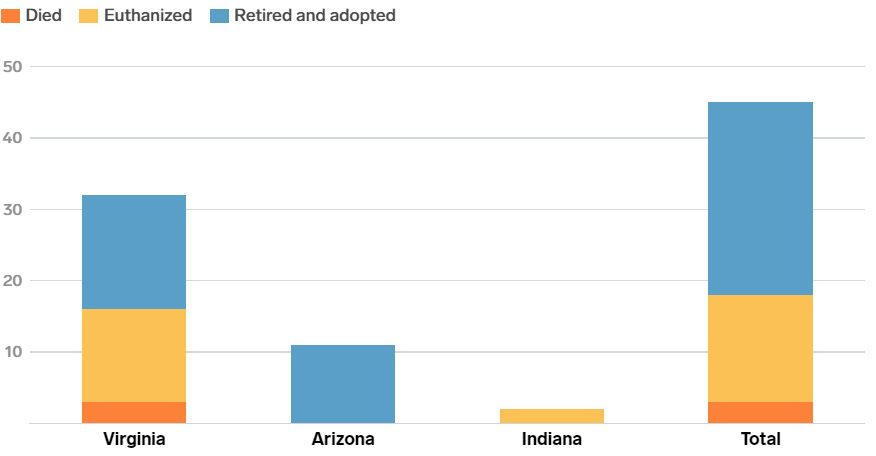

Through public-records requests, court documents, medical records, and interviews with dozens of bite victims, Insider documented at least 295 incidents where attack-trained dogs bit incarcerated people over the six years from 2017 to 2022. Insider identified one attack in Connecticut, to break up a fight in 2020; three in Massachusetts, all in the context of forced cell extractions, in 2020; five in Indiana; 15 in Arizona; and 271 attacks in Virginia.

The use of attack-trained dogs is legal in multiple states

At least 12 states authorize the use of attack-trained dogs in prisons; Insider confirmed that 8 have deployed them in recent years for attacks or shows of force.

The locations of the bites indicate that many of the men may have been prone when they were attacked; a 2006 study suggested that bites to the head, neck, and torso are more likely when the target is on the ground, hiding, or partially restrained.

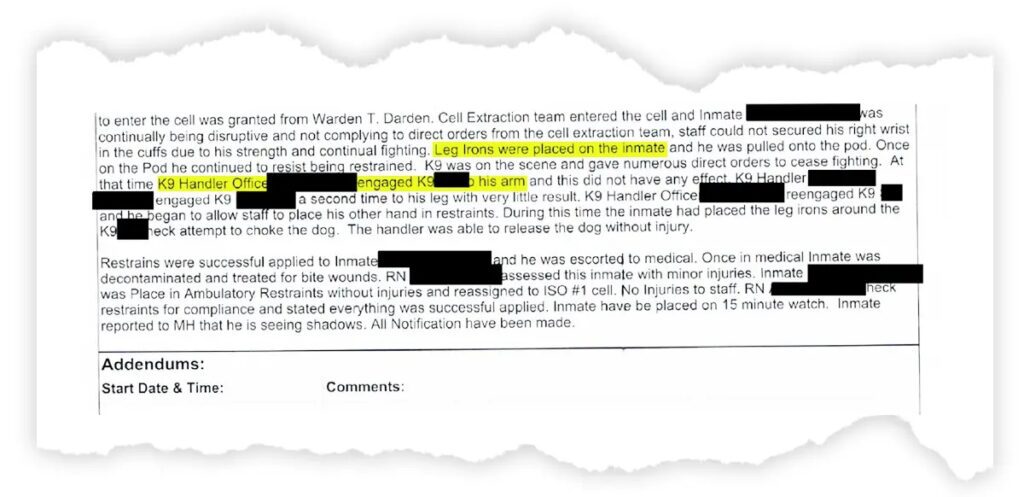

Several men described being cuffed or compliant, spread-eagled on the ground, when attacked; one incident report from July 2022 documents that a man in a Virginia facility called Sussex II State Prison was attacked by a patrol dog after he’d been wrestled into leg irons.

Virginia Department of Corrections

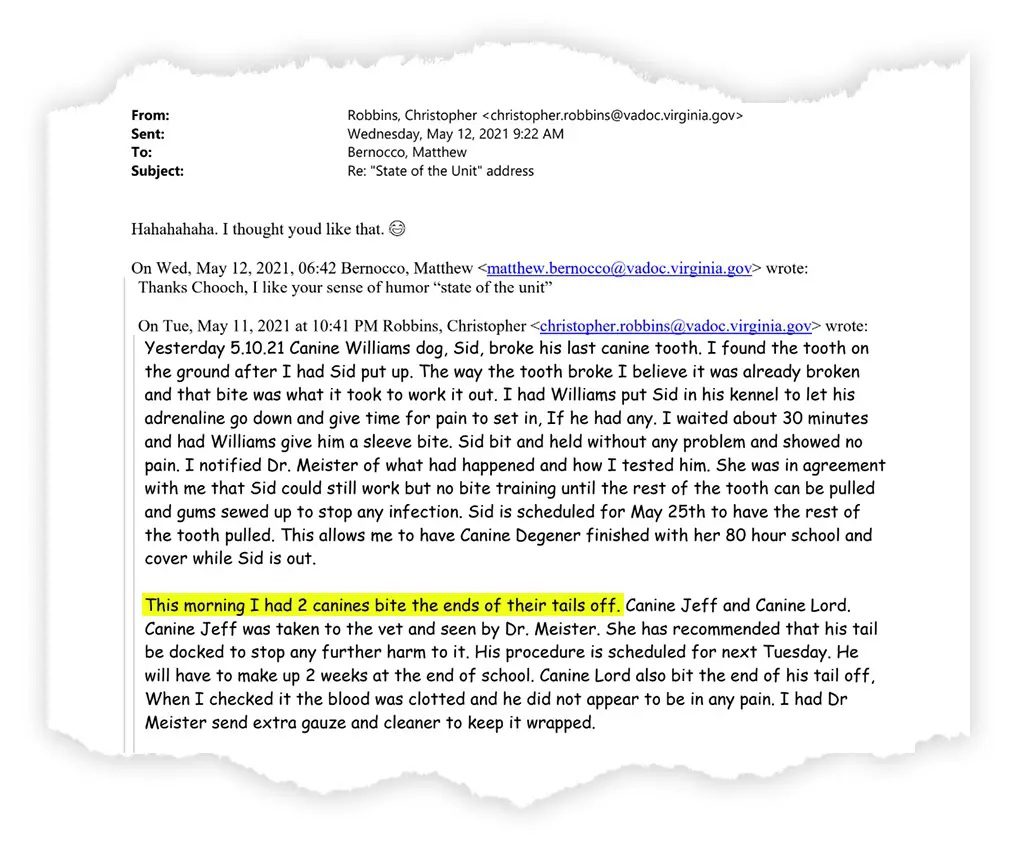

The bites are severe, sometimes permanently disabling and disfiguring. Dozens of people said the terror of being attacked by a dog caused them acute distress, such as recurring nightmares or other symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. The process of being conditioned to such extreme violence leaves many of the dogs in a state of intense distress themselves. More than one has bitten off his own tail.

State prison systems that employ attack-trained dogs say their use makes facilities safer for those who are incarcerated and those who guard them. Departments argue that the presence of the dogs alone — their barking and snarling — is so intimidating that it deters many violent incidents from taking place. When employed as a use of force, prison administrators say, the dogs replace corrections officers in dangerous situations like breaking up violent fights or forcibly removing a person from their cell, a tactic known as a cell extraction. Yet no studies have established the efficacy of using attack dogs in correctional settings, and records reveal they are deployed differently by each state that uses them.

In Arizona, the department’s dogs are trained to search for narcotics and contraband and to attack on command, and they are kept muzzled except when they’re being deployed to bite. In Indiana, they’re used to detect contraband, but also to patrol perimeters and apprehend escapees. Massachusetts requires wardens to seek permission from the state corrections commissioner every time they bring attack-trained dogs inside a prison facility, and they’re approved only for “major disorders” such as cell extractions. In Iowa, patrol dogs are authorized to bite, but over six years from 2016 to 2021, patrol dogs never bit a single prisoner, despite being present at 19 cell extractions, according to records Insider obtained through a public-records request.

Virginia deploys prison attack dogs far more than any other state

The Virginia Department of Corrections is an extreme outlier, commanding dogs to attack on an unmatched scale. Records show that Virginia prisons deploy patrol dogs to attack incarcerated people as a routine use of force in the state’s six high-security prisons: Keen Mountain, Sussex I, Sussex II, Wallens Ridge, River North, and Red Onion. Insider documented one additional attack at Augusta, a medium-security facility. In a court filing, the department said roughly one in every seven deployments resulted in attacks. Insider was able to document 271 attacks in Virginia state prisons from 2017 to 2022, through court filings and internal incident reports. Through a legal settlement with the state department of corrections over a public-records request, Insider and the University of Virginia School of Law First Amendment Clinic obtained bite reports for 149 of these attacks.

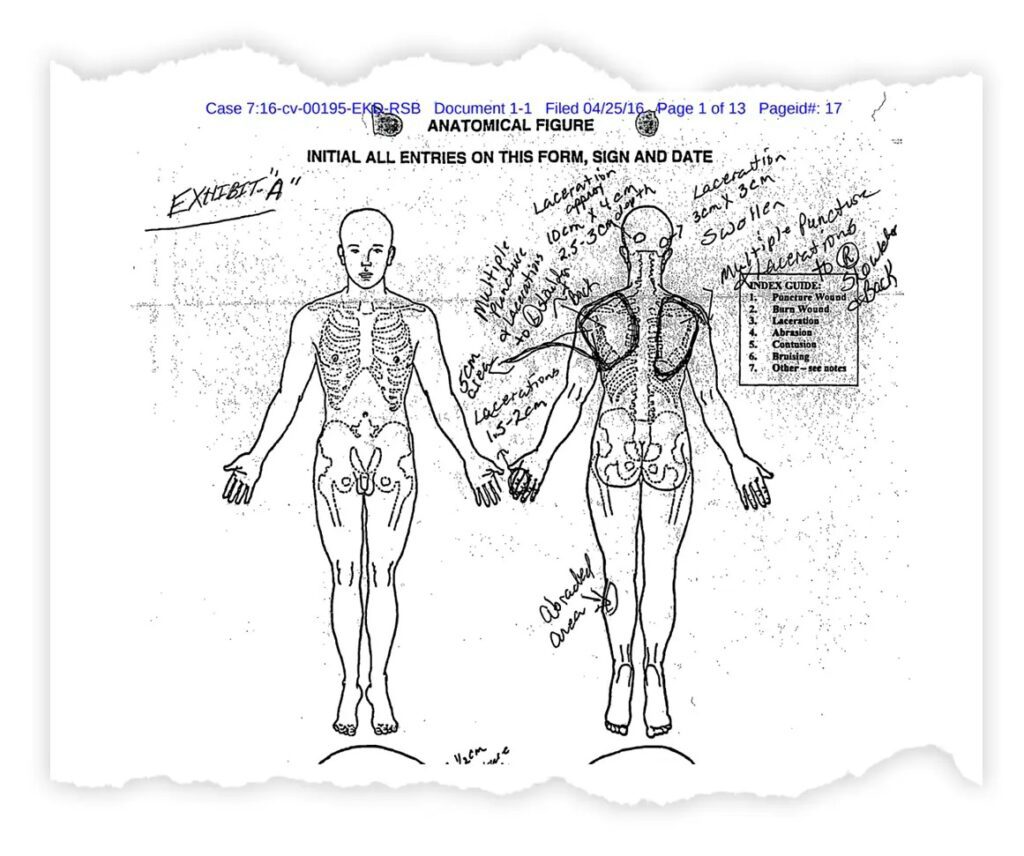

The severity of the wounds caused by the attacks betrays the tremendous force the dogs can wield. Medical records obtained by Insider contain evidence of deep puncture wounds, lacerations with torn edges, and crush injuries in which muscle, nerves, and bones were damaged from the pressure of the dog’s jaw. A study using data from the 1980s and 1990s in Los Angeles found bites from attack-trained dogs were more medically serious than bites from domestic pet dogs. The authors found people bitten by trained law-enforcement dogs were more likely to be hospitalized and require surgeries for skin grafts or tendon and arterial repairs. Dog mouths are also loaded with bacteria. A 1994 dog-bite study found a correlation between the depth of the bite and an increased risk of developing serious infections.

In at least 18 incidents, bite victims in Virginia were wounded so severely by attack-trained dogs that they were transferred to nearby hospitals to be treated for crush injuries, extensive muscle and tissue damage, or septic infections. Others were found to have symptoms of trauma.

A patrol dog named Jerko attacked Jeremy Defour at Sussex II in 2018, biting and tearing his buttocks and genitals, according to court records. The attack went on for a full minute as he lay prone, while he begged for the handler to pull off the dog. He was later diagnosed with PTSD.

Bert, a patrol dog at Wallens Ridge State Prison, bit Antwon Whitten seven times across his back, shoulders, head, face, and hands during a cell extraction in 2015, according to court filings and internal incident reports. Multiple lacerations split his face from the corner of his nostril to his jawline. Healthcare workers stitched his bite wounds with 55 internal and external sutures, according to his medical paperwork.

Bite locations indicate men may have been prone when attacked

An analysis of Virginia patrol dog bites from 2017 to 2022 shows bites to the head, neck, and torso. One study said such bites are more likely when a target is on the ground, hiding, or partially restrained.

In response to Insider’s findings, a spokesperson for the Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation, and Reentry said the department was under new leadership and would be reviewing all of its policies and practices, including its use of dogs.

Other departments defended their current protocols. The Indiana Department of Correction said all its dogs were trained “using the appropriate K9 industry standards.” The Delaware Department of Correction said department dogs “assist officers in meeting their safety and security mission.” A spokesperson for the Virginia Department of Corrections said the department’s use of patrol dogs was governed by operation procedures authorized by Virginia law.

Though Insider documented three dog attacks in Massachusetts in 2020, a spokesperson for the state department of corrections said patrol dogs were deployed only to intimidate and “do not engage in use of force tactics.” The department, the spokesperson said, “remains committed to de-escalation.” New Jersey deployed patrol dogs at least once in recent years, according to court filings — to “restore order” at South Woods State Prison in April 2020. A spokesperson for the New Jersey Department of Corrections said the department’s use of patrol dogs conforms to state guidelines on use of force and that no patrol dog had bitten an incarcerated person “in more than a decade.”

Departments of corrections in Iowa and Connecticut did not respond to queries.

Tri-State Canines training facility, Warren, Ohio

Virginia Department of Corrections patrol dogs are typically Belgian Malinois, Czech shepherds, or German shepherds. These breeds were once developed for herding but now dominate the ranks of military and law-enforcement canines because they are intelligent, robust, energetic working dogs with a deeply encoded instinct to protect.

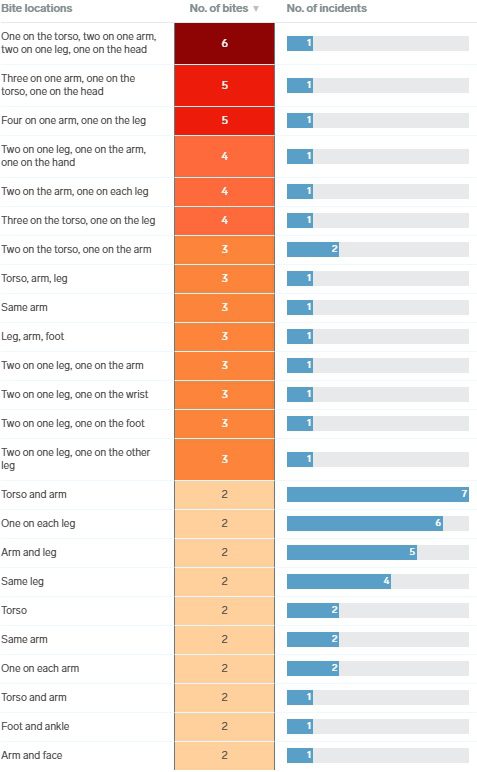

An attack dog’s bite is powerful enough to puncture sheet metal. On people, the bites rend skin and muscle. Department patrol dogs are trained to bite once and hold to minimize flesh tears and lacerations. However, in nearly 30% of the bite reports Insider analyzed, Virginia patrol dogs bit more than once or “readjusted” their bites to different body parts in response to a victim fighting or thrashing in pain. The dogs bit arms and legs most commonly but also bit stomachs, faces, hands, feet, hips, shoulders, and genitals. In at least 15 cases over the past six years, Virginia dogs mauled people all over their bodies, biting them three, four, or even six times and leaving wounds on their arms, legs, shoulders, faces, chests, and hands.

Dozens of men incarcerated in Virginia were bitten multiple times

Over the past six years, Virginia dogs bit at least 15 people three, four, or even six times in a single attack.

Most attack-trained law-enforcement dogs are bred in central, eastern, and northern Europe where there’s a long tradition of training dogs from puppyhood to compete in elite patrol-dog competitions. In these competitions, dogs score points for tracking, obedience, and “protection” — attacking a person in a bite suit on command. The training methods used by some competition hobbyists are notoriously cruel. Videos released by Oikeutta eläimille, a Finnish animal-rights organization, show German trainers beating, kicking, and using electric and prong collars to shock and suffocate their dogs until they yelp in pain.

When these dogs retire from competition, some are sold to American importers like Dave Blosser, the owner of Tri-State Canine Services, a company that sources and trains dogs for US law-enforcement agencies and prison and jail systems. A retired police-dog handler himself, Blosser travels to Europe in search of dogs who possess what trainers call “drive,” a potent combination of ferocity, intense energy, desire to work, and aggression.

“We’re not looking for Fluffy,” Blosser said. “My dog would take down Satan.”

US District Court, Western District of Virginia

He imports the dogs to his training facility, a converted warehouse in Warren, Ohio. Some of the dogs arrive “hard,” too aggressive to handle after getting their “ass kicked over in Holland,” Blosser said. He sometimes deprives the most reactive dogs of food and water for a few days. Once they stop fighting him, he begins to train them for their new job: searching for narcotics, chasing a fleeing suspect, or attacking a human being on command.

One day last July, Blosser demonstrated how he conditions a dog to respond to threats with aggression. He led a Belgian Malinois up onto a small plywood table at his training facility and chained him to a metal pole. The handler and other trainers yelled, struck the concrete flooring with cloth bullwhips, and threatened the dog with padded wooden poles until he was defensive and agitated. He barked, a sharp clanging sound that echoed off the cinder-block walls. They continued until the dog was intensely aroused, slavering and chomping. Blosser then approached wearing a padded bite sleeve and pressed the dog’s boundaries until he attacked, biting the canvas and jerking his head sharply back and forth.

Eli Hiller for Insider

Later that day, Blosser headed to an abandoned elementary school outside Canton, Ohio, where he conducts more advanced training sessions. He sent a volunteer decoy wearing a 35-pound padded bite suit to stand in the corner of a classroom. The suit reeked of sweat and dog mouth, and the dog could smell it from yards away. He panted in anticipation.

As the dog and his handler burst into the classroom, the handler shouted a sharp “stellen” — the German command for bite. The dog lunged forward and up toward the decoy’s chest, biting the suit on his arm just above the elbow. The dog held the bite, dragging his weight against the decoy. The man screamed and thrashed to simulate a victim in pain.

These exercises focus on building aggression and confidence, Blosser said. He wants the dogs to “dominate the guy, knock the guy down.” Teaching control comes later.

“If you apply too much brake in the beginning, you shut the dog down,” he said.

When a dog’s senses are flooded with novel stimuli — the smell of fear hormones and real panicked screams — even a well-trained canine might balk and refuse to attack. You won’t know how a dog will really react, Blosser said, until he’s been “blooded” on a first bite in the field.

Blosser flipped through dozens of photos of dog bites on his phone. Trainers and law-enforcement canine handlers send them to one another, he said, like trading cards. He identifies one woman, her eyes red from crying and arm littered with bite wounds, as a pet-shop assistant who tried to help put a new vest on a police dog. Another shows a canine trainer like himself, his neck gashed open from a dog’s tooth that split his skin from throat to ear.

Patrol school, Wallens Ridge State Prison

Matthew Johnson, a former Virginia canine officer at Wallens Ridge, picked out his last patrol-dog partner personally from a purveyor like Blosser in Connecticut, a massive German shepherd with a giant, jug-like head named Oscar. Johnson put his fingers through the metal loops of the kennel fencing and Oscar growled at him immediately. That’s the one, he thought.

When Johnson first began training Oscar, the dog whipped around and bit Johnson on the arm, leaving a pair of scars that mangled one of the four horsemen on his forearm tattoo. Stitches still fresh, Johnson returned the next day to work with Oscar, thrilled.

“A dog that’ll bite a handler will bite an inmate,” he said.

Once Johnson managed to gain control of Oscar, the pair was assigned to Wallens Ridge in 2018. Oscar was a smart dog, Johnson said, and strong — difficult to physically handle. When Oscar would hear “10-18” over the radio, the call sign used to report a fight, he’d race toward the pod doors. He was “hard,” Johnson said; he bit with more strength and ferocity than any other dog Johnson had ever handled.

That same year, Boris, a 92-pound German shepherd, went through patrol school and was assigned to his first handler in June at Wallens Ridge. A year earlier, a patrol dog named Cajos was trained, certified, and sent to Sussex I.

A-5 Pod, Red Onion State Prison

In 2017, Duran lay on the top bunk in his cell at Red Onion State Prison.

He heard shouts as a fight broke out on the top tier of the 44-cell pod and the quick blasts of officers firing less-lethal rounds. At Red Onion, these are typically “pepper balls” — plastic bullets filled with pepper spray.

Two men ran into Duran’s cell and dived onto the floor, as Duran heard the barking of dogs from his upper bunk. An alarm sounded and the cell doors began to slide shut for lockdown. A fourth man scrambled madly at the door, trying to drag his torso through into the cell. He was too late. A patrol dog clamped its teeth around the man’s lower leg and dragged him out of the cell, screaming.

Of the 149 bite reports Insider obtained from the Virginia Department of Corrections, there were six reports of bites from 2017 at Red Onion. Only one closely matches the circumstances described by Duran: the March 15, 2017, attack on Linwood Mathias.

The report is spare. “Canine [redacted] engaged offender [redacted] on the lower left leg in the calf area,” the handler writes.

Lucas Pruitt for Insider

This is what Mathias remembers: being shot at with less-lethal rounds before he dropped to the floor by the cell door, face down, arms outstretched. Feeling teeth like an alligator’s bite down on his lower leg. The dog pulling him out of the cell and into the common area, thrashing its head side to side. The dog’s teeth tearing into his skin and muscle.

The dog releasing only to bite his calf a second time. His own screams. The moment he stopped screaming and lay still. The way his lower leg looked like ground beef.

Duran likely witnessed all of this more than two years before he was attacked himself.

An ambulance took Mathias to Mountain View Regional Hospital in Norton, Virginia, a half-hour drive away from the prison, where he stayed for 13 days. He required 42 stitches and three surgeries over 11 days to clean and debride the wound for infections that left his leg red and swollen from calf to groin.

Mathias first used a wheelchair, then a walker. He spent months in painful physical therapy. But the crush of the bite left his calf muscle permanently frozen. Years later, at his home in Portsmouth, Virginia, he still uses a cane on days when his leg swells and aches with severe nerve pain.

He now lives with intrusive memories that won’t let him go. The searing pain of the attack, the revolting feeling of the dog’s teeth in his leg. He also can’t shake the memory of the canine handler yelling racial slurs as the dog attacked. “Get ’em, boy!” he yelled. “Get that n—.”

Later, when he returned to Red Onion from the hospital, Mathias remembers, another corrections officer said, “I wish I could tie you to my bumper and drag you down the street.”

A third officer told him, “We wish you lived out there, so we could shoot you like deer.”

‘White man’s country’

Mathias was one of seven Black men attacked by prison dogs in Virginia prisons from 2011 to 2022 who allege in court filings or in interviews with Insider that corrections officers yelled racial slurs or taunts during or immediately after the attacks.

Xavia Goodwyn said in a civil complaint that a corrections officer used racist epithets as he was being attacked by a dog called Lojzo at Red Onion in 2015. As the canine officer sicced Lojzo on him, he said in an interview, the other officer held him down and repeatedly called him a “n—.” Four other Black men attacked by dogs in recent years at Wallens Ridge, River North, and Red Onion said in court filings or in interviews that officers hurled the N-word at them as a patrol dog was biting into their flesh.

Edris Lufti/Insider

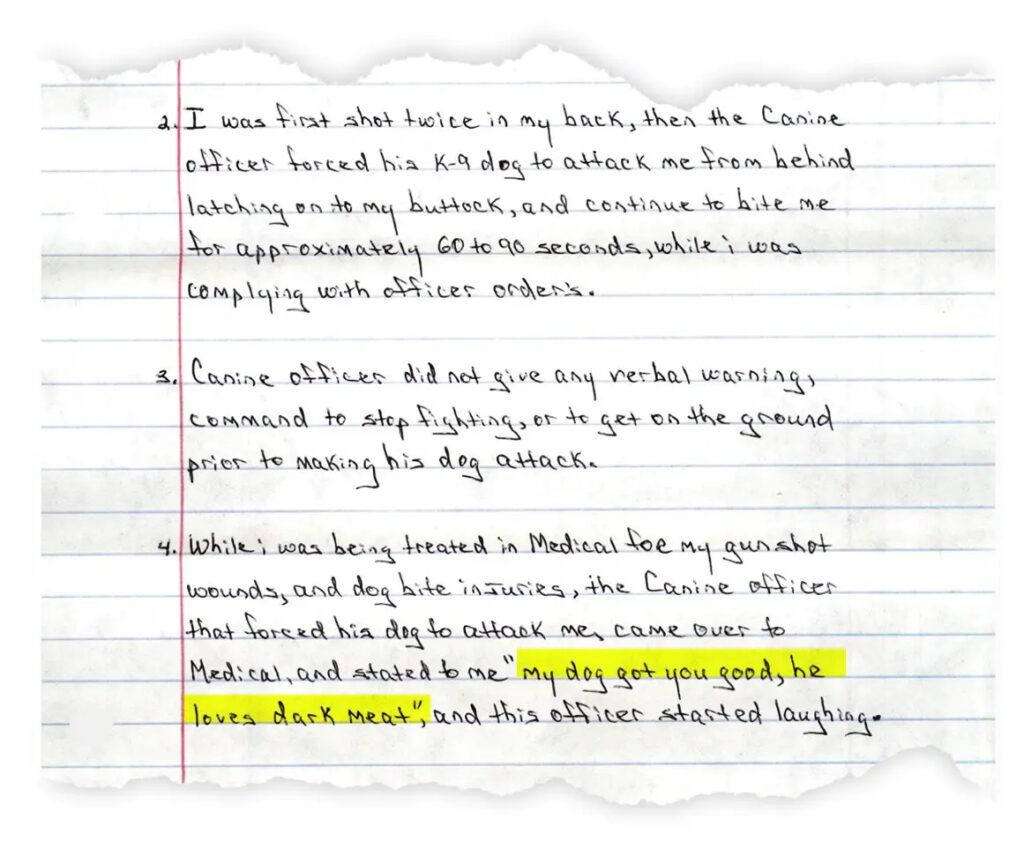

When Michael Watson got into a fight at Red Onion in 2020, he was shot twice with less-lethal rounds before a patrol dog clamped into his back and buttocks for “60 to 90 seconds,” according to an affidavit. The handler later visited Watson while he was receiving treatment for his wounds in the prison medical clinic. “My dog got you good,” Watson recalled the handler saying as he laughed. “He loves dark meat.”

After Thomas Rose was shot with a less-lethal round and blasted with pepper spray after being attacked by another man at River North Correctional Center in 2020, incident reports show, a dog named Tom bit him on his right leg so severely that his shoe filled with blood. As he stumbled toward the medical office, he later alleged in a civil complaint, he heard a mocking taunt from a corrections officer: “Black lives matter.”

Corrections officers denied the allegations of racism against Goodwyn and Rose in separate court filings. Officers did not respond to Watson’s allegations because he made them in an affidavit supporting another, unsuccessful, civil complaint.

Rose and Goodwyn each lost their cases at bench trials when judges said they had failed to prove that the attacks violated the constitutional protection against “cruel and unusual punishment” enshrined in the Eighth Amendment. The judge in Rose’s case found that the officers had issued warnings and that the dog was not used “maliciously or sadistically” — the legal standard required to find an Eighth Amendment violation — “but, rather, in a good faith effort to restore order.” In Rose’s grievance file, obtained by Insider, the department found “no violation of procedure” in the attack.

US District Court, Western District of Virginia

When asked about the allegations of racial violence, Rick White, who has served as warden at Red Onion since 2021, said he was not aware of any situations in which officers had used racist language. The Virginia Department of Corrections did not respond to Insider’s questions about individual cases.

Red Onion and Wallens Ridge prisons, in deep rural Virginia near the Kentucky border, have each been repeatedly investigated for allegations of racism by prison staff. Human Rights Watch found in 1999 that Red Onion guards routinely subjected Black prisoners to racial slurs, taunts, and physical threats. In 2000, the FBI opened an investigation into Wallens Ridge after 108 prisoners transferred there from New Mexico filed civil-rights lawsuits alleging they were subject to racist taunts and epithets. One attorney said a guard had threatened to turn prisoners over to the Ku Klux Klan.

Virginia Department of Corrections officials responded to the Human Rights Watch report by calling it “biased and inaccurate.” In 2000, Ron Angelone, then director of the Virginia Department of Corrections, called the allegations of racism and excessive force at Wallens Ridge and Red Onion “lies from convicted felons who don’t like being locked up in tough prisons.”

The following year, in 2001, the Connecticut Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities, a government agency charged with enforcing the state’s anti-discrimination laws, also investigated Wallens Ridge, as a number of Connecticut prisoners were contracted to be housed there. The commission’s report found that Connecticut prisoners there had been called racist slurs, shot at with rubber bullets, and taunted with songs about lynching.

“Yo, Black boy, you in the wrong place,” a prisoner cited in the report recounts a guard saying. “This is white man’s country.”

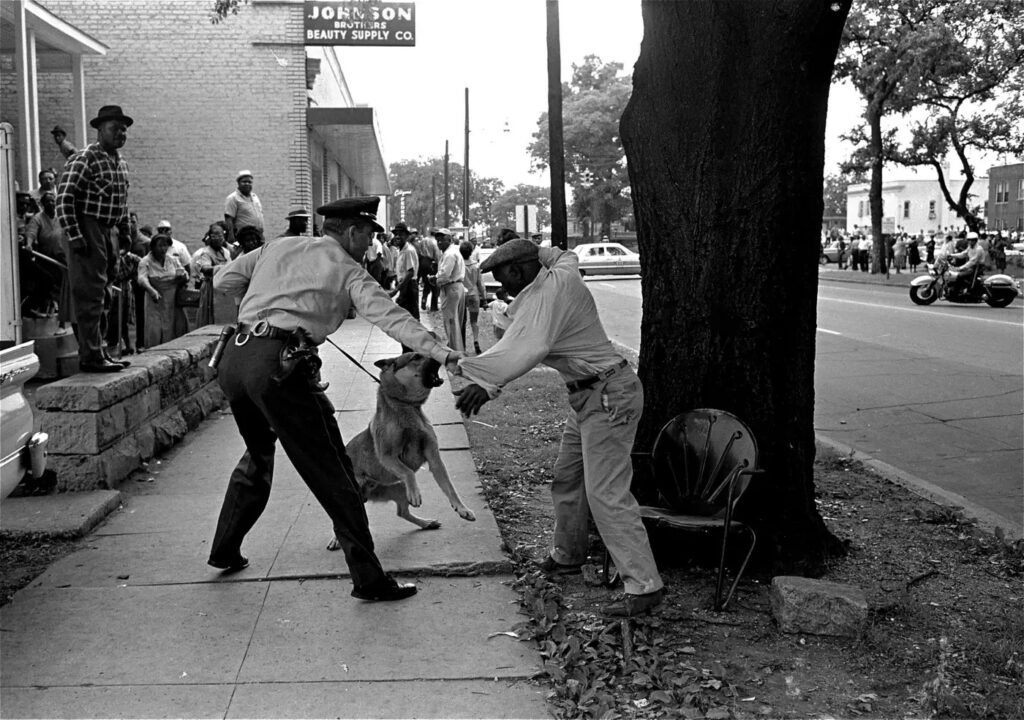

Birmingham, Alabama, 1963

Dogs have a long history of being deployed to terrify and attack Black and Indigenous people in the United States. Tyler Parry, an assistant professor of African American and African diaspora studies at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas, and Charlton Yingling, an assistant professor of history at the University of Louisville, study the history of weaponized dogs in the Americas. Attack-trained dogs have helped violently enforce white supremacy, Parry said, from executing indigenous Taino people in the Caribbean, to hunting down those who tried to escape slavery in the American South, to attacking civil-rights protesters in the 1960s.

“The dog has always been intended to strike a certain fear amongst the person that’s detained or oppressed,” Parry said. He called their use a form of “racialized terror.”

Bill Hudson/AP

Many slaveholders believed that dogs could sense race, Parry said, that they could be specifically trained to hunt for the scent of Black bodies. Breeders honed these so-called “negro dogs” as manhunters, selecting for sense of smell, strength, tenacity, and aggression to hunt, run down, and sometimes execute people fleeing slavery. By the 1840s, these dogs were commonplace throughout the United States, Parry and Yingling found.

In his 1853 memoir, “Twelve Years a Slave,” Solomon Northup describes his pursuit by dogs during an escape attempt. “Each moment I expected they would spring upon my back — expected to feel their long teeth sinking into my flesh,” Solomon recounted. “There were so many of them, I knew they would tear me to pieces, that they would worry me, at once, to death.”

A century later, in May 1963, when thousands of Black children poured into the streets of Birmingham, Alabama, to join the protests against segregation, the city’s notorious police commissioner, Eugene “Bull” Connor, met them with force. He ordered white officers to point fire hoses at the protesters and to sic German shepherds on the young students. In one photo, captured by Bill Hudson, a white police officer grabs Walter Gadsden, a 15-year-old high-school student, as a German shepherd lunges, teeth bared, at Gadsden’s torso.

“A hundred years ago they used to put on a white sheet and use a bloodhound against Negroes,” Malcolm X said in an interview not long after the protests. “Today they have taken off the white sheet and put on police uniforms and traded in the bloodhounds for police dogs.”

After the brutal crackdown on people protesting the killing of Michael Brown by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, a half a century later, the Department of Justice investigated the Ferguson Police Department and found a range of civil-rights abuses. These included the excessive use of dogs to attack people, including children, in routine police encounters. In every case where racial information was available, Ferguson police officers had sicced their dogs on Black people.

Officers, the report found, “appear to use canines not to counter a physical threat but to inflict punishment.”

Cell 15, P-2 Housing Unit, Souza-Baranowski Correctional Center

There are more than 370 maximum-security prisons in the United States, and the overwhelming majority do not use attack dogs at all.

Yet in Virginia, attack dogs are used, in the words of one corrections department court filing, as a “manpower multiplier” and routinely patrol most areas of the prison. They’re a frequent sight in the general population housing units, called pods, that are divided into two 22-cell horseshoes stacked two tiers high; along the concrete pathways, called boulevards, that lead from the residency buildings to the chow hall, classrooms, and visitation rooms; and at the boundaries of the fenced-in recreation yards.

Jeffery Moustache/Insider

Rick White, the Red Onion warden, told Insider the dogs were primarily used for “presence” — in other words, that the implied violence of their growls and bared teeth is sufficient to frighten people into compliance. He said the canine program has created a safe environment, allowing Red Onion to provide group educational and religious programs. While Insider documented three attacks at Red Onion in 2022, White said dogs were deployed for “presence” more than 200 times that year.

Three former department employees confirmed to Insider that they’re used primarily for deterrence. But according to an internal department record submitted in a court filing, dogs were deployed in Virginia to attack prisoners about four times a month, on average, from April 2016 to June 2022. Incident reports record patrol dogs being commanded to attack when prisoners do not immediately comply with orders from corrections officers, when prisoners are fighting, or for cell extractions.

When a man refuses to leave his cell, Virginia canine handlers are authorized to send in their dogs to bite him until he complies. On Christmas Day 2018, in Sussex I, Curtis Garrett ran away from corrections officers breaking up a fight and barricaded himself in his cell. Two dogs, Hurricane and Lojzo, and their handlers were sent in to extract him. In the process, the dogs badly mauled Garrett on his arms and legs, according to a civil complaint. An attorney representing the department later argued to a judge that it was necessary to sic the dogs on Garrett to prevent him from harming himself.

Kathleen Dennehy became a corrections commissioner for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 2004, a period when the state allowed the use of attack dogs. Dennehy, who left that post in 2007 and now serves as a corrections consultant, quickly emerged as a critic of the use of attack-trained dogs in prison settings. “A dog going into a cell for the purpose of disarming someone or forcing compliance, to me, is a human-rights violation,” she said. “The potential is there to do some serious injury.”

Aaron Fedor for Insider

Cell extractions are necessary only when someone is threatening to harm themselves or others, Dennehy explained. In those cases, she said, the best evidence-based practice is to deploy a dedicated health worker and a specially trained team of corrections officers who are properly outfitted with body armor, shields, and body cameras to enter the cell and wrestle the person out using as little force as possible.

Dennehy acknowledged that prisons are tinderboxes, and that any small altercation can quickly explode into violence. In these cases, she said, de-escalation is the priority. If force is required, it should be the minimum force necessary — pepper spray, for example — to ensure prisoner and staff safety.

“You don’t go into a situation thinking you’re going to escalate it and use the maximum force to resolve it quickly,” Dennehy said. “The goal is to try to use the minimal amount.”

But a dog cannot be trained to bite with the minimum necessary force, Jimmy Stanley, the canine sergeant at Red Onion from 2012 to 2021, said last year in a deposition. Their bites cannot be checked, only directed.

Jeffery Moustache/Insider

Dora Schriro, the director of the Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation, and Reentry from 2003 to 2009, discontinued using attack-trained patrol dogs in Arizona prisons in 2006. “The idea that you would have to revert to the dog, particularly one that’s trained to attack, is beyond extreme,” she said.

Dennehy banned the use of dogs to bite prisoners in Massachusetts state prisons that same year. “I didn’t see any instances where we should be sending dogs in to potentially rip flesh off of inmates,” she said.

Yet after Schriro and Dennehy left their jobs, both departments reintroduced the use of attack-trained dogs.

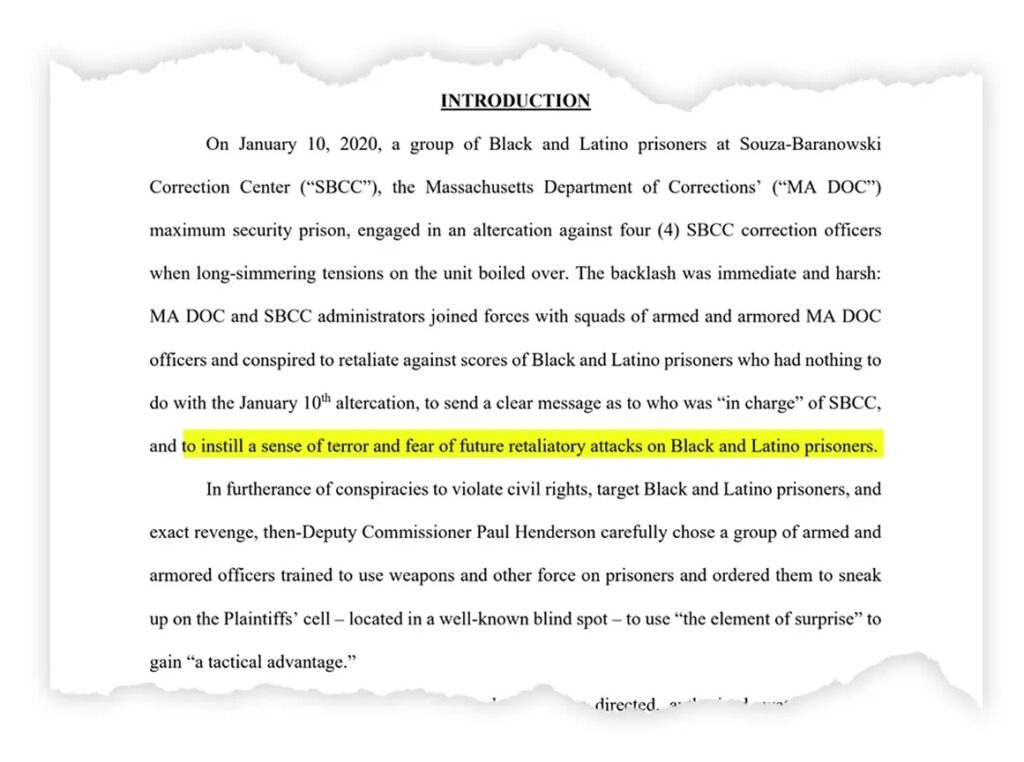

In January 2020, over 10 years after dogs were reintroduced in Massachusetts prisons, a patrol dog at Souza-Baranowski Correctional Center called Omar bit Dionisio Paulino during a cell extraction, tearing off a “chunk of his upper thigh,” according to a civil complaint and incident reports. In the complaint, Paulino and his cellmate, Robert Silva-Prentice, allege the attack on Paulino was part of a retaliatory campaign in response to an earlier incident in which prisoners had injured three officers. The guards, they allege, used beatings, dogs, Tasers, and pepper spray “to instill a sense of terror and fear of future retaliatory attacks on Black and Latino prisoners.”

United States District Court, District of Massachusetts

Prison officials said in court filings that the force deployed in January 2020 was necessary to maintain facility security. They also denied that the use of force was retaliatory or excessive. The case is pending.

In May 2023, court filings revealed the existence of a previously secret federal grand jury, which was investigating the bite inflicted on Paulino and other related allegations of brutality and retaliatory violence from prison guards. A federal review of the January 2020 incident could potentially result in federal criminal indictments against state officials for civil-rights violations. If charges are filed, civil-rights attorneys say, it could mark the first time federal criminal charges have been brought over an incident that involved the use of a dog to attack an incarcerated person.

Housing Unit 4, Sussex II State Prison

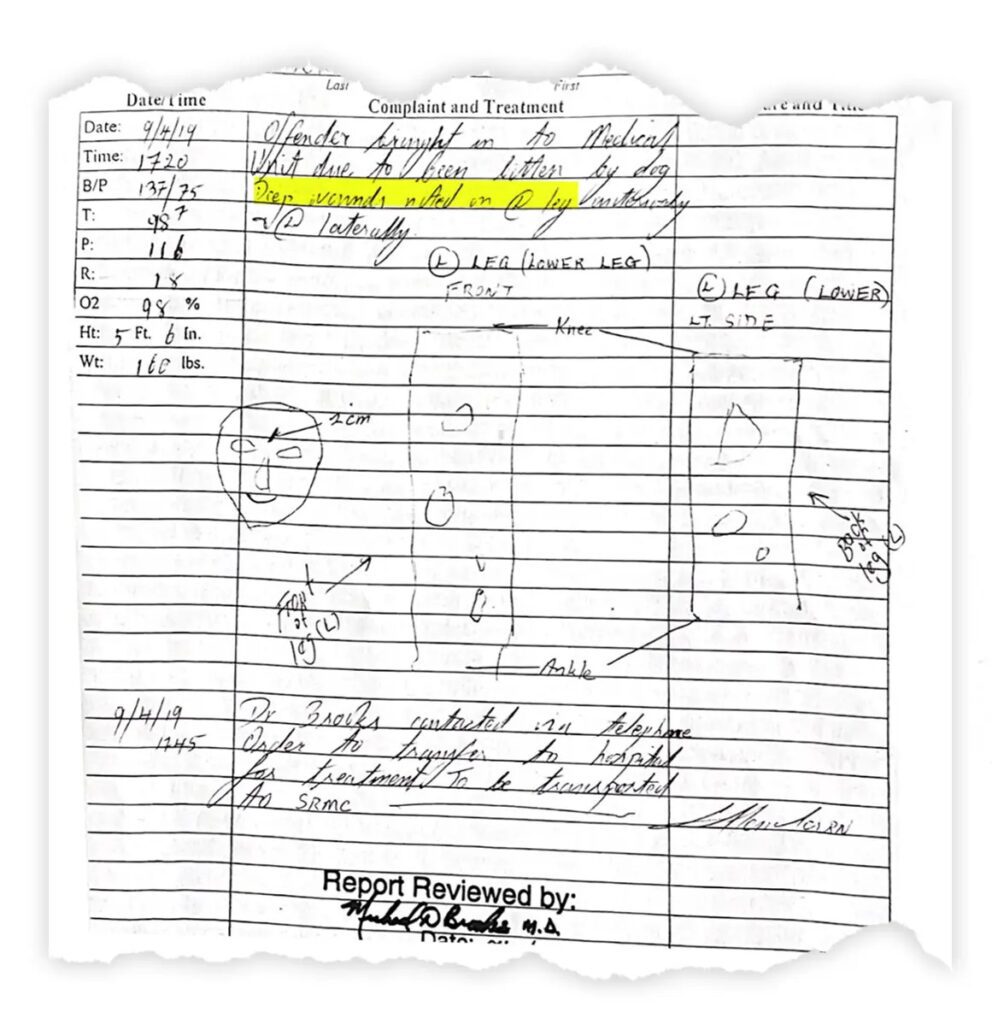

On September 4, 2019, a fight broke out on the upper tier of Adrian Duran’s housing unit at Sussex II, incident reports show. The brawl involved at least a dozen people, including Duran. One of them hit Duran on the head, a blow that split his forehead near his right eyebrow; it bled badly, partially blinding him. In the chaos, he heard corrections officers arriving and fled down the stairs to the lower tier with several other men.

At the foot of the stairs, Duran ran his hands down his torso, checking for stab wounds, and tried to wipe the blood from his eyes. Then he heard a dog bark and a cold fear shot through his chest. A second later, a canine handler and her dog came screaming into the housing unit.

Duran spun and slammed himself chest down onto the floor — his feet toward the door, his head toward the stairs — facing the other prisoners who had also dropped to the floor. He glanced over his shoulder just as Cajos opened his mouth wide.

Cajos bit down on Duran’s lower left calf above the ankle. He felt a spike of intense pain as the dog’s teeth sank into his flesh, then a brutal pressure as Cajos crushed the muscle and bone of his leg between his jaws. Duran screamed so forcefully that flecks of blood and saliva hit the shocked face of the man on the floor in front of him.

The dog whiplashed his head from side to side. With each jerk, Duran felt his flesh tear in “cracking” splits as if someone powerful were forcing their fingers inside the punctures and ripping the wounds wider. He thrashed in panic and pain.

Duran begged the canine officer to remove her dog. She did briefly, then commanded Cajos to bite Duran a second time. He clamped down on the same leg, just below Duran’s knee.

Courtesy of Adrian Duran

Duran felt detached. He couldn’t scream anymore. The other men around him started to yell at the canine officer, desperately appealing to her to release the dog. Duran smelled a sharp metallic scent like copper pennies. It was the smell of his own blood spreading across the floor.

The canine officer pulled on the dog’s lead, dragging both Cajos and Adrian backward on the floor until Cajos finally released the bite. Duran lay on the floor in shock, willing himself to lose consciousness. Corrections officers rolled him onto a stretcher and took him to medical where a nurse sent him for emergency treatment.

It wasn’t until an emergency-department doctor unwound Duran’s bloodied gauze bandages that he saw his own leg for the first time. Puncture wounds the size of nickels with jagged edges covered his lower left leg. Strips of flesh sagged away from his leg where lacerations had sliced through skin, fat, and muscle tissue.

When the doctor bent to examine the wound, she inhaled in shock.

“A dog did this to you?” she asked.

Virginia Commonwealth University Health, Richmond, Virginia

Prison officials sent Duran back to Sussex II less than 12 hours later. Officers pushed him in a wheelchair, following a trail of his own dried blood down the concrete boulevard from the prison exit to the front doors of the residence building, and then straight to a segregation cell.

The cell was filthy, its walls plastered with old food, dirt, and human excrement. Duran lay on the metal bed in dim fluorescent lighting. He tried to keep his wounds protected in the laundered bed sheets. And he wondered whether it would be safe to take a shower, since the water at Sussex II always ran a dull rust brown. Despite Tylenol and Codeine, his leg ached ferociously. He couldn’t sleep.

A week and a half later a fever set in. His leg was severely inflamed — swollen, red, and hot to touch. His medical records show that he was prescribed antibiotics, but he said they were never dispensed. A nurse came to check on his fever, Duran said, and immediately ordered him sent for more emergency care. For four days Duran was treated at Virginia Commonwealth University Health for sepsis, a potentially fatal systemic infection, according to his medical paperwork.

Segregated Housing Unit, Red Onion State Prison

US District Court, Western District of Virginia

After Duran returned for the second time to Sussex II, his life in prison changed. He dropped out of his GED course to avoid passing the dogs barking and lunging in the yard on the way to his classroom. He had intrusive daydreams that the dogs might break their leads and chase him down the boulevard. He woke often in the middle of the night, drenched in sweat.

In one recurring dream, he hits the ground running, the dogs at his heels. He’s fast; they’re faster. He can’t outrun them. At a full sprint he slams into a chain-link fence and tries to haul his weight up and over to safety. Teeth close around his lower left leg. Desperate, he claws at the metal loops, straining against the dog’s weight. He can’t hold on; his fingers slip. As the dogs rip him off the fence, his body jolts awake.

The dream is now as familiar as the cold fluorescent light of his cell.

Dozens of other incarcerated people bitten by patrol dogs say the attacks severely damaged their mental health. Many suffer from panic attacks, anxiety, nightmares, and depression. Some have been diagnosed with PTSD months and years after the attack, according to psychiatric and mental-health treatment records submitted in court filings.

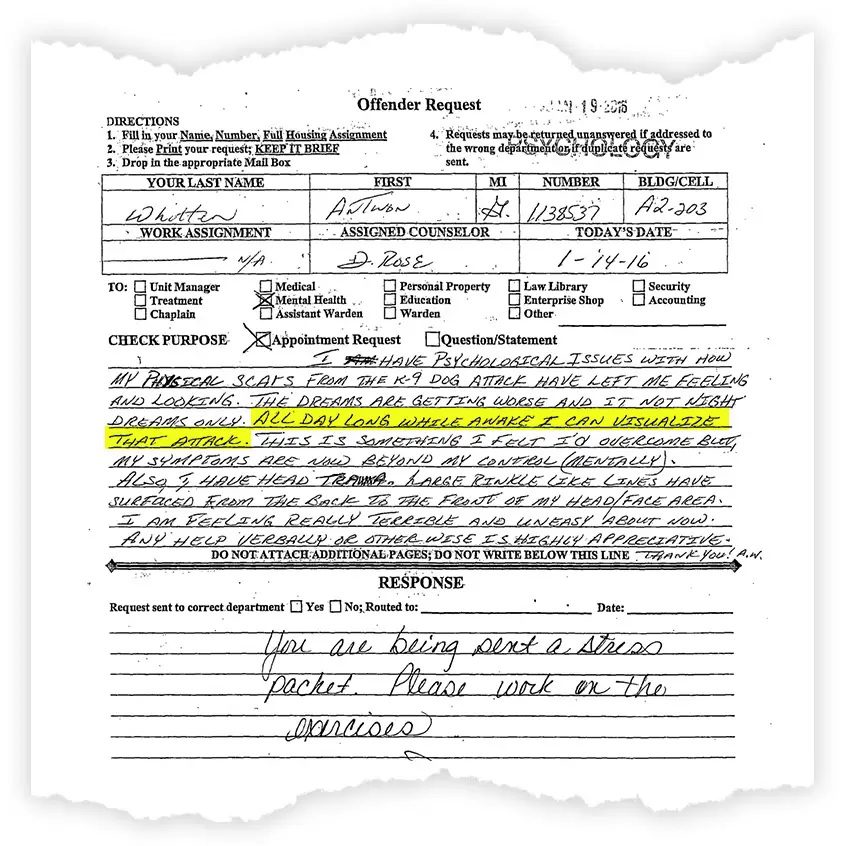

Antwon Whitten was bitten on his head, face, arm, and shoulder at Wallens Ridge in 2015 by a dog named Bert. He wrote on a mental-health request form submitted in court filings that he was struggling to come to grips with his heavy facial scarring; he was experiencing depression and nightmares. “All day long while awake I can visualize that attack,” he wrote.

Curtis Garrett, the man attacked by two dogs in a Sussex I cell extraction, said in a January 2021 court filing that he had suffered relentless nightmares, anxiety, and symptoms of PTSD. He was institutionalized in a state psychiatric hospital, his amended complaint says, for a mental breakdown caused by the trauma of the attack.

US District Court, Western District of Virginia

Jeremy Defour had such intense panic attacks and flashbacks after being attacked that he received a formal PTSD diagnosis. He was the one bitten by a patrol dog named Jerko on his buttocks and genitals at Sussex II. During that 2018 incident, he begged the canine officer to remove the dog. Instead, a second handler on the scene brought a barking dog right up to Defour’s face, according to a complaint he filed in federal court. “Shut the fuck up,” the handler said, “before I let my dog go too.”

The emotional fallout from the incident was dramatic. Rather than encounter the dogs in general-population recreation yards and residence pods, Defour chose to spend the next three years in solitary confinement, pacing alone in an 8-foot-by-10-foot cell for 23 hours a day.

Whitten lost his case when a jury found that the attack was not malicious or sadistic; Garrett and Defour each eventually settled.

Patrol dog kennels, Virginia Department of Corrections

The patrol dog kennels are even smaller, at 6 feet by 10. The dogs run in compulsive circles around their enclosures, beating their tails against the chain-link fencing until they develop raw open sores.

The stress of the repeated attacks eventually breaks many of them.

“It’s not natural anymore for a dog to bite a man,” said Kenneth Licklider, the owner of Vohne Liche Kennels, in northern Indiana, which sources and trains dogs for law enforcement and for prisons and jails. Licklider, a military veteran, has also trained dogs for the US military, including dozens of explosive-detection dogs used by US troops in Iraq in 2004. He said a trainer must kindle a level of aggression in attack dogs “that went out of them in the stone age.”

This requires pressure to a breaking point. Some patrol dogs begin to display compulsive behaviors and become destructive, cracking their own teeth chewing on concrete kennel walls and steel dog bowls. Others will attack themselves.

“This morning I had two canines bite the ends of their tails off,” a Virginia canine program administrator wrote in a 2021 email.

Virginia Department of Corrections

Working dogs like patrol canines that are exposed to prolonged high-stress environments and traumatic violence can become avoidant or hyperreactive, veterinary behaviorists with expertise in canine aggression told Insider.

Incident reports and internal emails contain evidence of prison attack dogs rejecting their brutal assignment. A canine handler reported in 2018 that he tried to force his dog to bite a prisoner three times, but the dog “attempted to back out of his collar trying to get away.” Chris Robbins, a Virginia patrol canine sergeant, wrote in a 2021 email that a dog called Rivan had refused to bite someone. He ended up sending Rivan back to patrol canine school to “build his aggression up.”

At the Virginia patrol school, trainers build aggression by teaching dogs to “hate everyone but their handler,” Matthew Johnson, the former canine officer, told Insider. The dogs cannot be touched, handled, or praised by anyone else.

A veterinary technician who treated patrol dogs at a clinic in Lebanon, Virginia, said she was told not to touch the patrol dogs in her care without their handler present. The technician, who asked not to be named, fearing retaliation, said she’d sometimes sneak a pet on a dog’s nose pressed against the kennel door or push treats between the bars.

“They’ve experienced no kindness,” she said. “No kindness whatsoever.”

Some dogs become indiscriminately aggressive.

Southwest Virginia Veterinary Services, Lebanon, Virginia

On March 26, 2020, that same vet tech was called into the exam room to assist with a routine checkup for a patrol dog named Boris, a 92-pound German shepherd from Red Onion. Boris was muzzled but was in a state of visible agitation. He was foaming at the mouth and “extremely aggressive” toward the veterinarian and his own handler, Stephen McReynolds, according to an incident report.

McReynolds asked her and the veterinarian to leave the room. Through a slot in the closed door, the technician watched McReynolds pull Boris to the floor in an effort to get him under control as the dog fought to free himself, even trying to bite his handler through the muzzle. Eventually, McReynolds wrapped an arm around the dog’s neck and pressed his other hand against the dog’s chest. The technician heard Boris cry and struggle, then saw him lie still. McReynolds then called the vet tech and the veterinarian back into the room.

While McReynolds continued to hold Boris in a headlock, the technician said, she started to draw blood from the dog’s back leg. Then she noticed Boris begin to urinate. She felt for a pulse and snapped at the handler to release him. Documents show the dog had stopped breathing. The veterinarian started CPR, but Boris was declared dead soon after.

McReynolds did not respond to queries; the Virginia Department of Corrections said it does not comment on personnel matters.

A necropsy report obtained by Insider found that Boris had died of “acute respiratory distress syndrome that resulted in cardiopulmonary arrest.” Small purple spots found on the lung tissue included in the report suggested that blood clots had formed in his lungs because of the constriction of his airway, the technician explained.

“I was horrified,” she said. “He killed that dog.”

A backyard outside Waverly, Virginia

Due to their extreme reactivity, Virginia patrol dogs who are no longer suitable for work can be adopted only by a former handler, by department policy. This is their sole path to retirement.

Daniel Clinton, a former Virginia canine handler, adopted two of his former dog partners: first Tom, then Riko. Clinton kept the dogs in kennels in his backyard outside Waverly, Virginia, to give them time to decompress. He played with them outside with basketballs they’d pop between their curved teeth and let his kids carefully feed them kibble to teach him to trust them. Eventually, Tom became so docile, he said, “so ready to be loved, to be a pet,” that he got to come inside. (Insider could not confirm whether he is the same Tom who bit Thomas Rose.) He would lay down on the living-room floor and delicately eat potato chips fed to him by Clinton’s 6-year-old daughter.

Other adoptions are a struggle. Johnson, the former Virginia canine officer, adopted Fuga, a German-shepherd mix who was retired after he broke all four canine teeth on bites. Fuga remained so aggressive, Johnson said, that he had to keep the dog in a kennel in his backyard, surrounded by a 6-foot-high fence. If Fuga escaped, “the first thing he might do is bite a kid,” Johnson said.

Some dogs are too dangerous to ever be adopted. In Virginia, four dogs were euthanized for aggression, destructive behavior, or liability risk in 2021 alone. The following year, another dog was euthanized after severely biting handlers at Wallens Ridge, Sussex I, and River North, according to an internal email and incident reports.

“I have tried to put him in a muzzle several times to work with him but it is nearly impossible,” Chris Robbins, the Virginia patrol canine sergeant, wrote in an email on May 2, 2022. “We are going to keep having these issues,” he wrote, “if we keep trying to rehabilitate him.” The dog was euthanized three days later.

Many attack-trained prison dogs are euthanized or die on the job

From 2017 to 2022, records show a little more than half of patrol dogs exited the program alive.

From 2018 to 2022, another 12 dogs were euthanized or discovered dead in their kennels. Two years after he bit Adrian Duran, Cajos died of heat stroke suffered during a training exercise. He collapsed, vomiting blood, and was euthanized a day later, according to an incident report.

Exterior, Red Onion State Prison

In the last year of his sentence, Duran, now 33, began to cautiously imagine his life outside.

He got married in January to Jamie Elliott, a former nurse at Sussex II. Elliott and Duran had gotten to know each other when she did medical calls on his pod; she quit her job in June 2021 when she realized she and Duran had feelings for each other. Like Duran, Elliott was scared of the patrol dogs, who often lunged and snapped at her, straining at their leads as she walked the boulevard between prison buildings. They felt to her like a constant reminder of how punitive and intimidating the prison was.

Courtesy of Adrian Duran

The couple wed in the Red Onion visitation room in front of the guard booth. Duran couldn’t stop smiling. In their wedding photo, the two of them are posed against the blue wall of the prison’s visitation room. Elliott loops her arms around him and hugs him close. Now they talk on the phone every day, about their families, Elliott’s new nursing job, and ordinary details of her daily life outside. Occasionally they squabble over whether Duran will be able to tolerate the presence of Bodhi, Elliott’s 12-year-old chihuahua, when he comes home to her.

Some days his future feels guaranteed. Elliott sends him pictures of the flowering crabapple trees in front of the exit doors of Red Onion, and he imagines walking past them the day he leaves. He imagines taking long walks in the mountains with no one else around. He imagines meeting his new nephew before the baby learns to walk.

Other days his leg aches, and when Jamie asks about his day he has nothing to say that won’t frighten her.

Like the day last spring when Duran was in his cell on the top tier right at the moment Jawan Lee was returned to the pod from another residence hall. Boisterous and funny, with a quick smile and expressive hands, Lee took a spin around to greet everyone before walking up to his own top-tier cell, right by the stairs.

A group of corrections officers arrived with the lunch cart, according to a grievance document later filed by Lee, and began to release the men in clusters to retrieve their trays. Just as Lee walked out onto the stairs, another man ran out from an unsecured bottom tier cell and tackled him, pinning him on his back.

Lee fought back. A corrections officer sprayed Lee directly in the eyes and mouth with pepper spray. From his top tier cell, according to an affidavit he filed later, Duran watched a handler pull a patrol dog up onto its hind legs and drop it, bodily, on top of Lee. The dog bit into his lower right leg. Lee screamed.

The dog shook Lee’s leg like a rag doll. Duran, watching, broke out into a cold sweat. His stomach knotted. The dog pulled backward on Lee’s leg, tearing the muscle. Duran had to turn away. He doubled over on the corner of his bed near the wall and tried not to listen to Lee’s screams.

Later, Lee would tell Duran that when the nurses unwound the gauze around his leg he saw a chunk of flesh missing from his calf like “a half a tangerine.”

Lee remembered the nurse pointing to the wound. “I can see your bone,” she said.

This piece was republished from the Insider.